Set up to succeed – How well is NCEA Level 1 working for our schools and students?

Explore related documents that might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the students, parents and whānau, school leaders and teachers, employers, and others who shared their experiences, views and insights with us through interviews, group discussions and surveys. Thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories about what has and hasn’t worked. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give thanks to the 21 schools that accommodated our research team on visits and organising time in their school day for us to talk to students, teachers, and leaders. We also thank the teachers of the Subject Associations who talked to us about their experiences.

We appreciate the parents and whānau who gave their precious time to share with us stories about their children’s experiences and their views.

We acknowledge the considerable support of the Ministry of Education and the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) who provided us with guidance and data in a comprehensive manner.

We greatly appreciate the experts in our ‘Expert Advisory Group’ who have shared their understanding and wisdom to guide our evaluation and make sense of the findings.

We acknowledge and thank all the students, parents and whānau, school leaders and teachers, employers, and others who shared their experiences, views and insights with us through interviews, group discussions and surveys. Thank you for giving your time and sharing your stories about what has and hasn’t worked. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give thanks to the 21 schools that accommodated our research team on visits and organising time in their school day for us to talk to students, teachers, and leaders. We also thank the teachers of the Subject Associations who talked to us about their experiences.

We appreciate the parents and whānau who gave their precious time to share with us stories about their children’s experiences and their views.

We acknowledge the considerable support of the Ministry of Education and the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) who provided us with guidance and data in a comprehensive manner.

We greatly appreciate the experts in our ‘Expert Advisory Group’ who have shared their understanding and wisdom to guide our evaluation and make sense of the findings.

Executive summary

In 2024, changes to NCEA Level 1 were rolled out nationwide. Leaving school with a qualification leads to better life outcomes, so ensuring Aotearoa New Zealand’s qualifications work well is essential for the success of our young people.

ERO reviewed NCEA Level 1 to find out how fair and reliable it is, if it is helping students make good choices, how motivating and manageable it is for students, and the impacts of recent changes. We also explored how valued it is and how implementation has gone so far. This summary sets out what we looked and how, and the key findings and recommendations.

Leaving school with higher qualifications leads to a range of more positive life outcomes, including higher incomes and better chances of employment. Young people who leave school with NCEA Level 1, compared to those who leave without NCEA Level 1 are more likely to have employment income and less likely to receive a main benefit as adults.

What is NCEA?

The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main secondary school qualification. NCEA has three levels in which you can gain a qualification. NCEA Level 1 is usually offered in Year 11 when students are usually 15-16 years old, NCEA Level 2 is usually offered in Year 12, NCEA Level 3 is usually offered in Year 13.

Students earn credits by completing assessment in different subjects. A student needs 60 credits to achieve NCEA Level 1 and 20-credits in literacy or te reo matatini (reo Māori literacy) and numeracy or pāngarau (reo Māori numeracy).

What are the changes to NCEA Level 1?

Changes to NCEA Level 1 were brought in at the start of 2024. Key changes include:

- Providing a range of assessment formats (including submitted reports).

- Introducing new 20-credit co-requisite for literacy, numeracy, te reo matatini, and pāngarau.

- Fewer, larger standards through redeveloping subjects with four achievement standards – two internally assessed, two externally assessed – typically worth five credits each and 20 credits in total.

- Reducing the number of NCEA Level 1 subjects.

- Changing the requirements so 60 credits are required to pass NCEA Level 1 (plus the 20-credit co-requisite)

- Building aspects of te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori in achievement standards and assessment materials and ensuring te ao Māori pathways are acknowledged and supported equally in NCEA (te reo Māori and te ao haka).

What we did

ERO was commissioned to undertake a review of NCEA Level 1 to look at how implementation is working and at the impacts on students and schools so far. We have used a mixed methods approach to deliver breadth and depth and drew on a range of data and analysis, including:

- A review of the international and New Zealand literature.

- Administrative data from NZQA, the Ministry of Education, and the IDI.

- ERO’s own data collection, including:

- Over 6,000 survey responses – across teachers, leaders, Year 11 students, parents & whānau of Year 11 students, and employers of school leavers.

- Visits to 21 secondary schools – across regions and characteristics, including size, EQI, rural-urban.

- Interviews with over 300

Key findings

From our evidence, we have identified 14 key findings across eight areas. These findings need to be set in context. Student achievement reflects not only their learning in Year 11 but also their learning in Years 1-10. While each NCEA Level can be achieved independently, they can be thought of as a package. This puts focus on how the three Levels build coherently and collectively to prepare students for future pathways. Changes to Levels 2 and 3 are planned but not yet implemented. The New Zealand National Curriculum is also being refreshed.

Area 1: Is NCEA Level 1 valued?

We looked at whether and why different groups, including teachers, students, their parents and whānau, and employers value NCEA Level 1.

Finding 1: NCEA Level 1 remains optional. An increasing number of schools, mainly schools in high socio-economic areas, are opting out of offering it.

Finding 2: Students and parents and whānau mainly value NCEA Level 1 as a stepping stone to NCEA Level 2. Employers value other skills and attributes over NCEA Level 1.

Area 2: Is NCEA Level 1 now a fair and reliable measure of knowledge and skills?

We looked at whether the new NCEA Level 1 allows students a fair chance to show what they know and can do, and whether accreditation accurately and consistently reflects student performance.

Finding 3: NCEA Level 1 difficulty still varies between subjects and schools due to the flexibility that remains.

Finding 4: Authenticity and integrity are more at risk due to the changes, and the biggest concern is about submitted reports.

Finding 5: NCEA Level 1 is not yet a reliable measure of knowledge and skills.

Area 3: Is NCEA Level 1 helping students make good choices and preparing them for their future?

High-quality qualifications support students to make good choices and prepare them with the knowledge and skills needed for their future. We looked at whether NCEA Level 1 is well understood and whether it prepares students with the knowledge and skills they need for Levels 2 and 3, and for their future beyond school.

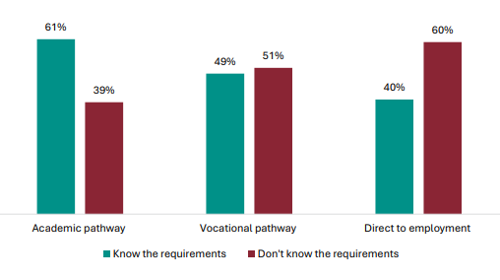

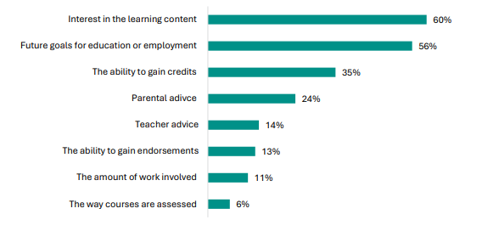

Finding 6: NCEA Level 1 remains difficult to understand, and it can be difficult to make good choices.

Finding 7: NCEA Level 1 wasn’t set up to, and so doesn't provide clear vocational pathways.

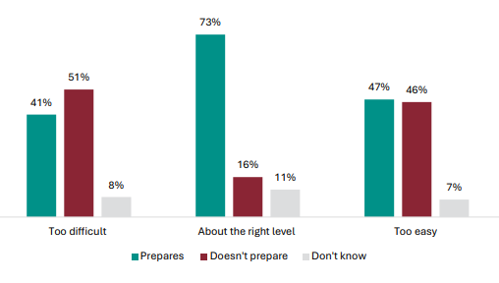

Finding 8: NCEA Level 1 isn’t always preparing students with the knowledge they need for NCEA Level 2.

Area 4: Is NCEA Level 1 motivating and manageable for students?

We looked at the extent to which NCEA Level 1 motivates students to engage in learning throughout the year and to achieve as well as they can, and whether their overall assessment workloads are manageable.

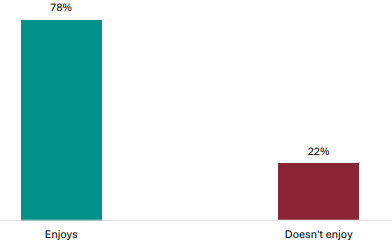

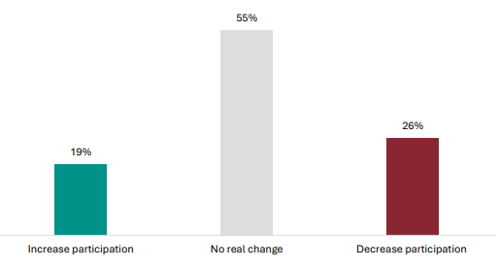

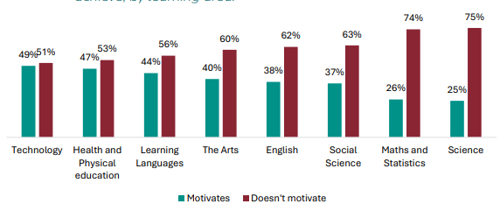

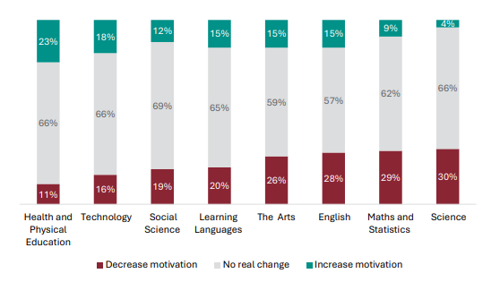

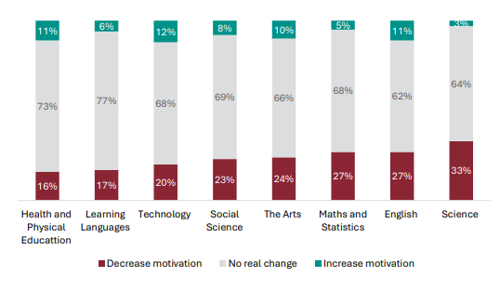

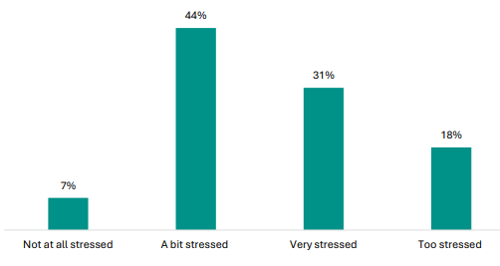

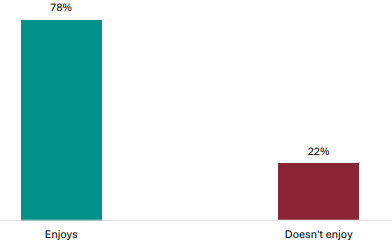

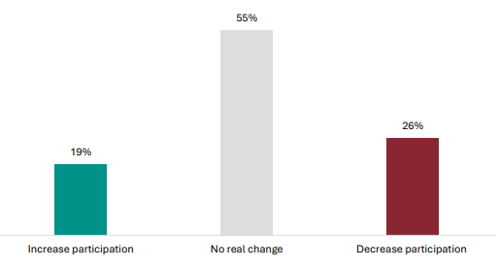

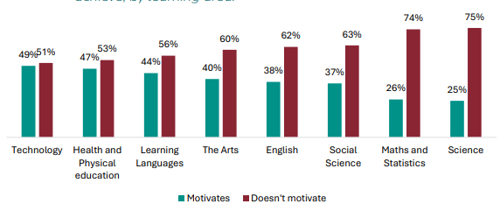

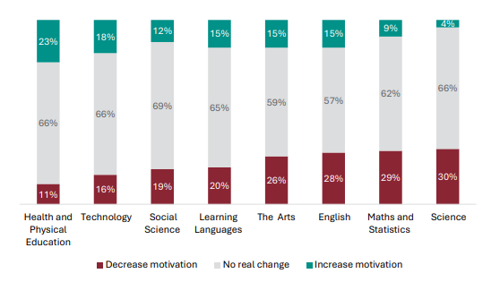

Finding 9: NCEA Level 1 is not motivating all students to achieve as well as they can, and some students disengage early.

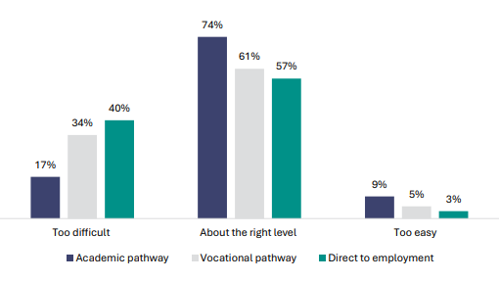

Finding 10: NCEA Level 1 is manageable, but not stretching the more academically able students.

Area 5: Is NCEA Level 1 working for all students?

All students should have the opportunity to achieve. We looked at how well NCEA Level 1 is working for a range of students.

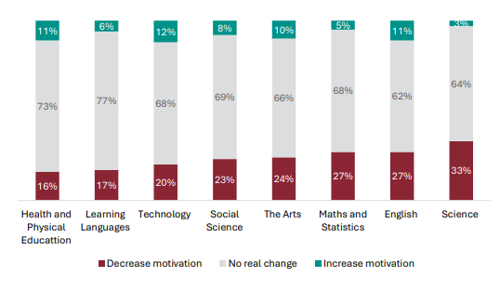

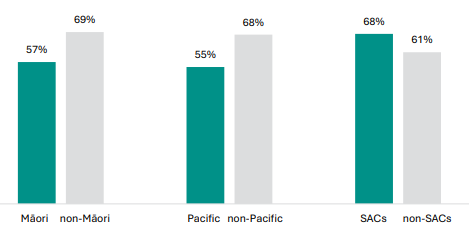

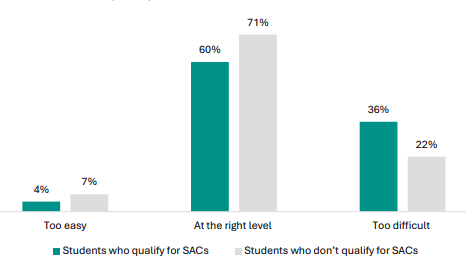

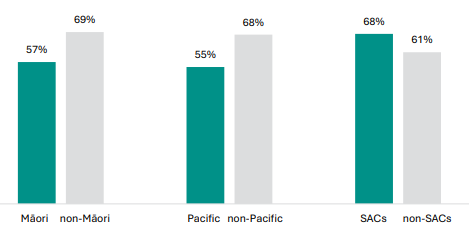

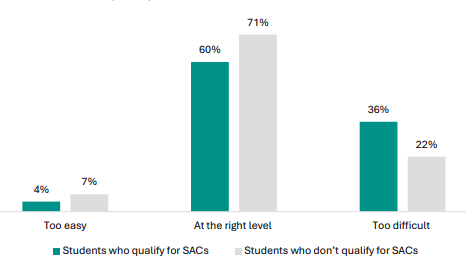

Finding 11: Some aspects for NCEA Level 1 aren’t working as well for Māori students, Pacific students, and students who qualify for Special Assessment Conditions (SACs).

Area 6: Is NCEA Level 1 manageable for schools?

We looked at whether teachers and leaders are finding NCEA Level 1 manageable, both in terms of preparing for and teaching the new achievement standards and administering assessments.

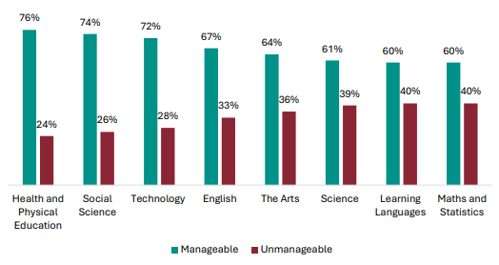

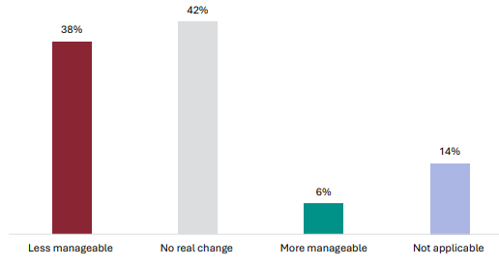

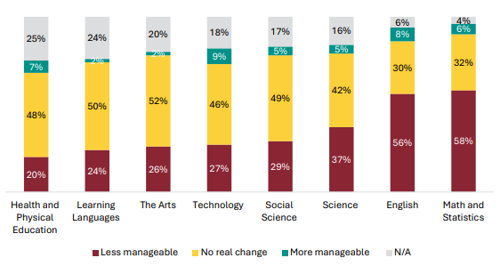

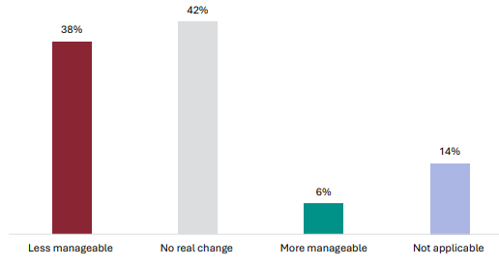

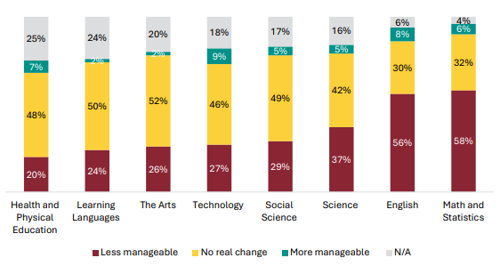

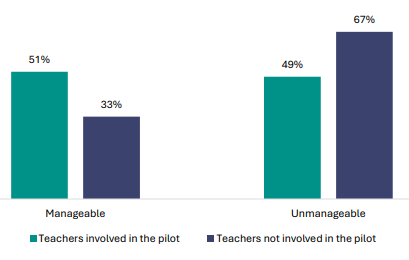

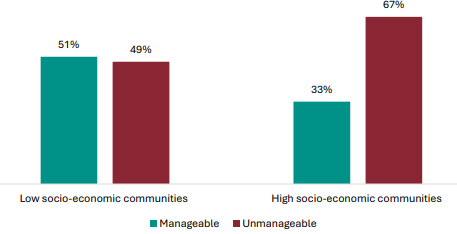

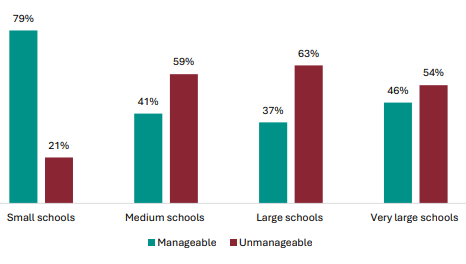

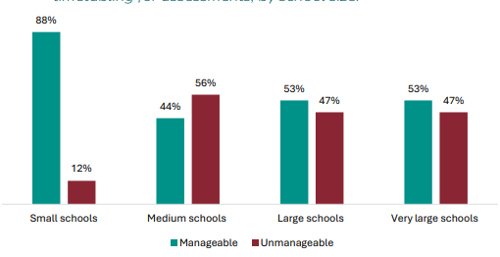

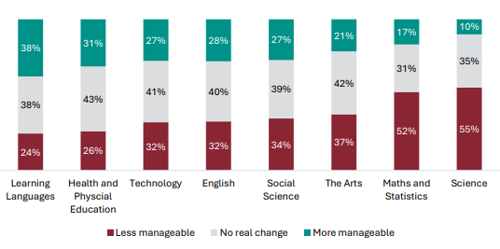

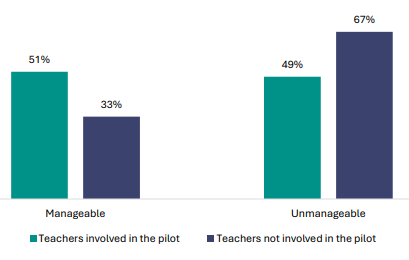

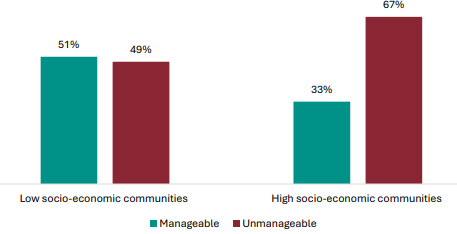

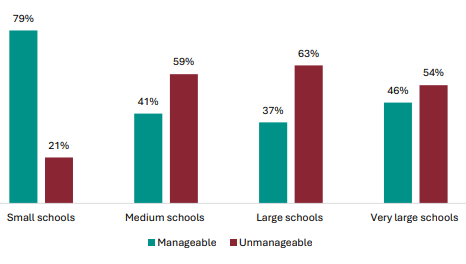

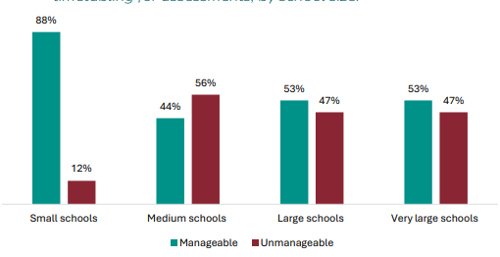

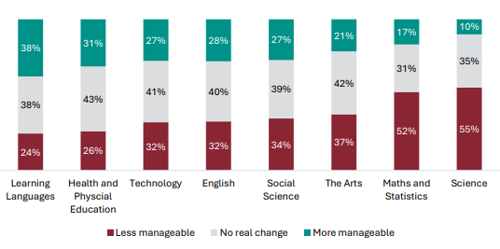

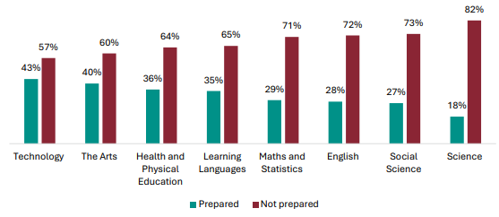

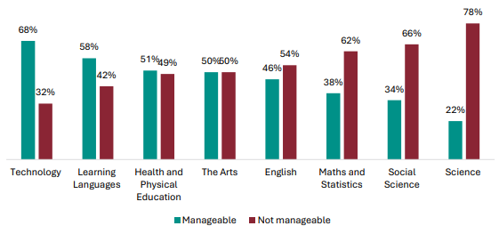

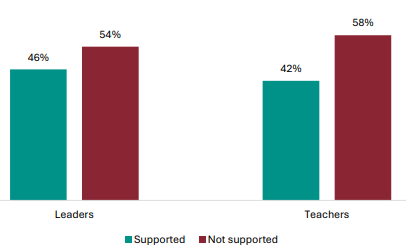

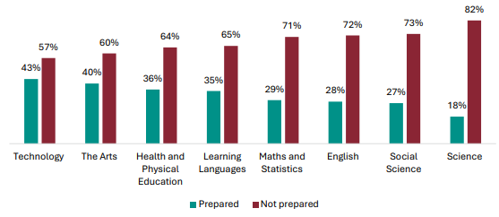

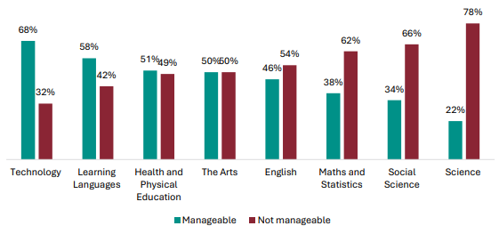

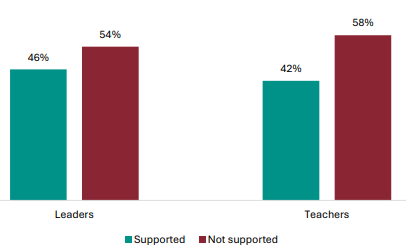

Finding 12: Schools are finding the new NCEA Level 1 unmanageable in its first year, and it is likely that some issues will remain after the initial change.

Area 7: What are the implications of the co-requisite?

From 2024, NCEA certification at any of the three levels, requires a 20-credit co-requisite. Currently, this can be achieved by participating in the co-requisite assessments, known as Common Assessment Activities (CAAs), or by gaining 10 literacy and 10 numeracy credits from a list of approved standards. We looked at how this change is being delivered and the impacts.

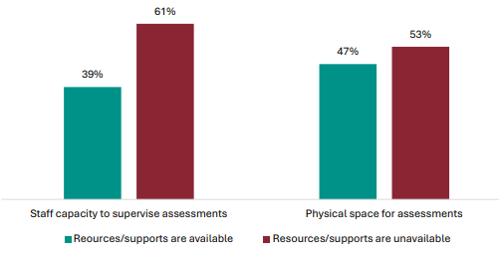

Finding 13: Schools value the standardisation introduced by the co-requisite, but administering the assessments is logistically challenging.

Area 8: What has and hasn’t worked from implementation – what lessons have we learnt?

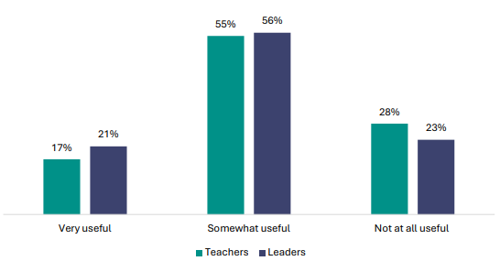

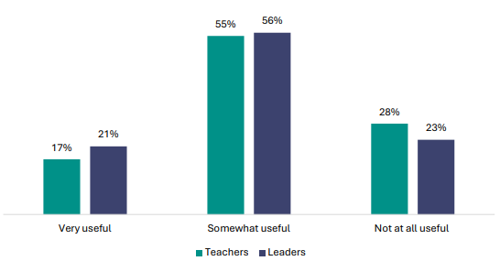

Change is always challenging. We looked at usefulness of resources and supports to help schools implement the changes to NCEA Level 1 and what can make it more manageable.

Finding 14: Implementation has not gone well.

Recommendations

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified four areas of recommendations:

Area 1: Quick changes

In order to improve the fairness and reliability of NCEA Level 1 and help schools to administer external assessments, ERO recommends the following quick changes.

Recommendation 1: Replace the submitted reports.

Recommendation 2: Resource schools for the additional external assessments.

Recommendation 3: Extend the transitional period for the literacy and numeracy requirements.

Recommendation 4: Rethink how external assessment is conducted for practical knowledge and skills.

Recommendation 5: Review achievement standards, where there’s concern, so that credits are an equal amount of work and difficulty.

Recommendation 6: Revisit whether achievement standards for some subjects are too literacy-heavy.

Recommendation 7: Provide results more quickly for the co-requisite.

Recommendation 8: Provide schools with exemplars for the full range of assessment formats.

Recommendation 9: Provide resources that schools can use to help parents and whānau understand the requirements for NCEA Level 1.

In order to allow schools to make the right choices for their students in the short-term. NCEA Level 1 should remain optional.

Recommendation 10: Keep NCEA Level 1 optional for now.

Area 2: Reform

To improve the quality and credibility of the qualification longer term, ERO recommends reform.

Recommendation 11: Decide on the purpose of NCEA Level 1 and revise the model to fit the purpose. The three main options are:

- Drop it entirely.

- Target it as a foundational qualification.

- Make NCEA Level 1 more challenging to better prepare students for NCEA Level 2 and stretch the most academically able.

Whichever model is adopted, to improve the reliability, fairness, and inclusivity, reform should also involve the following.

Recommendation 12: Reduce flexibility in the system.

Recommendation 13: Reduce variability between credits.

Recommendation 14: Retain fewer, larger standards to support deeper learning and reduce flexibility in the system but put more weight on assessments later in the year.

Recommendation 15: Strengthen vocational options and develop better vocational pathways.

Area 3: Implications for NCEA Levels 2 and 3

Some issues at NCEA Level 1 will also apply at NCEA Levels 2 and 3. ERO recommends changes at NCEA Levels 2 and 3:

Recommendation 16: Reduce flexibility in the system.

Recommendation 17: Decide on the model for NCEA across all three Levels.

Area 4: Lessons for implementation of future changes

Implementation of NCEA Level 1 has lessons for implementing further changes:

Recommendation 18: Sequence changes and signpost earlier.

Recommendation 19: Provide information, supports, and resources to schools earlier.

Recommendation 20: Involve experts in the changes.

Recommendation 21: Coordinate information and resources better.

Conclusion

Qualifications are important to life outcomes. These findings tell us that NCEA Level 1 still isn’t a fair and reliable measure of student knowledge and skills. Due to remaining flexibility in the system, the difficulty and the amount of work differ by school and learning area and students sometimes miss out on important subject knowledge. To improve the quality and credibility of NCEA, it is critically important to act on these findings and recommendations.

In 2024, changes to NCEA Level 1 were rolled out nationwide. Leaving school with a qualification leads to better life outcomes, so ensuring Aotearoa New Zealand’s qualifications work well is essential for the success of our young people.

ERO reviewed NCEA Level 1 to find out how fair and reliable it is, if it is helping students make good choices, how motivating and manageable it is for students, and the impacts of recent changes. We also explored how valued it is and how implementation has gone so far. This summary sets out what we looked and how, and the key findings and recommendations.

Leaving school with higher qualifications leads to a range of more positive life outcomes, including higher incomes and better chances of employment. Young people who leave school with NCEA Level 1, compared to those who leave without NCEA Level 1 are more likely to have employment income and less likely to receive a main benefit as adults.

What is NCEA?

The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main secondary school qualification. NCEA has three levels in which you can gain a qualification. NCEA Level 1 is usually offered in Year 11 when students are usually 15-16 years old, NCEA Level 2 is usually offered in Year 12, NCEA Level 3 is usually offered in Year 13.

Students earn credits by completing assessment in different subjects. A student needs 60 credits to achieve NCEA Level 1 and 20-credits in literacy or te reo matatini (reo Māori literacy) and numeracy or pāngarau (reo Māori numeracy).

What are the changes to NCEA Level 1?

Changes to NCEA Level 1 were brought in at the start of 2024. Key changes include:

- Providing a range of assessment formats (including submitted reports).

- Introducing new 20-credit co-requisite for literacy, numeracy, te reo matatini, and pāngarau.

- Fewer, larger standards through redeveloping subjects with four achievement standards – two internally assessed, two externally assessed – typically worth five credits each and 20 credits in total.

- Reducing the number of NCEA Level 1 subjects.

- Changing the requirements so 60 credits are required to pass NCEA Level 1 (plus the 20-credit co-requisite)

- Building aspects of te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori in achievement standards and assessment materials and ensuring te ao Māori pathways are acknowledged and supported equally in NCEA (te reo Māori and te ao haka).

What we did

ERO was commissioned to undertake a review of NCEA Level 1 to look at how implementation is working and at the impacts on students and schools so far. We have used a mixed methods approach to deliver breadth and depth and drew on a range of data and analysis, including:

- A review of the international and New Zealand literature.

- Administrative data from NZQA, the Ministry of Education, and the IDI.

- ERO’s own data collection, including:

- Over 6,000 survey responses – across teachers, leaders, Year 11 students, parents & whānau of Year 11 students, and employers of school leavers.

- Visits to 21 secondary schools – across regions and characteristics, including size, EQI, rural-urban.

- Interviews with over 300

Key findings

From our evidence, we have identified 14 key findings across eight areas. These findings need to be set in context. Student achievement reflects not only their learning in Year 11 but also their learning in Years 1-10. While each NCEA Level can be achieved independently, they can be thought of as a package. This puts focus on how the three Levels build coherently and collectively to prepare students for future pathways. Changes to Levels 2 and 3 are planned but not yet implemented. The New Zealand National Curriculum is also being refreshed.

Area 1: Is NCEA Level 1 valued?

We looked at whether and why different groups, including teachers, students, their parents and whānau, and employers value NCEA Level 1.

Finding 1: NCEA Level 1 remains optional. An increasing number of schools, mainly schools in high socio-economic areas, are opting out of offering it.

Finding 2: Students and parents and whānau mainly value NCEA Level 1 as a stepping stone to NCEA Level 2. Employers value other skills and attributes over NCEA Level 1.

Area 2: Is NCEA Level 1 now a fair and reliable measure of knowledge and skills?

We looked at whether the new NCEA Level 1 allows students a fair chance to show what they know and can do, and whether accreditation accurately and consistently reflects student performance.

Finding 3: NCEA Level 1 difficulty still varies between subjects and schools due to the flexibility that remains.

Finding 4: Authenticity and integrity are more at risk due to the changes, and the biggest concern is about submitted reports.

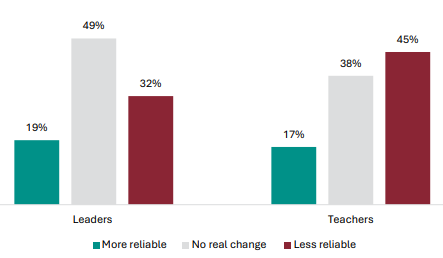

Finding 5: NCEA Level 1 is not yet a reliable measure of knowledge and skills.

Area 3: Is NCEA Level 1 helping students make good choices and preparing them for their future?

High-quality qualifications support students to make good choices and prepare them with the knowledge and skills needed for their future. We looked at whether NCEA Level 1 is well understood and whether it prepares students with the knowledge and skills they need for Levels 2 and 3, and for their future beyond school.

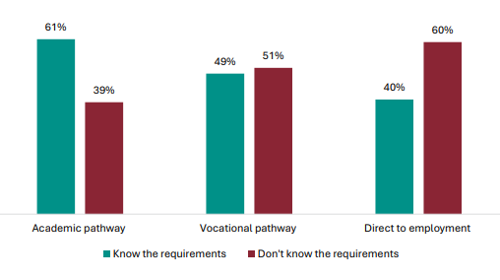

Finding 6: NCEA Level 1 remains difficult to understand, and it can be difficult to make good choices.

Finding 7: NCEA Level 1 wasn’t set up to, and so doesn't provide clear vocational pathways.

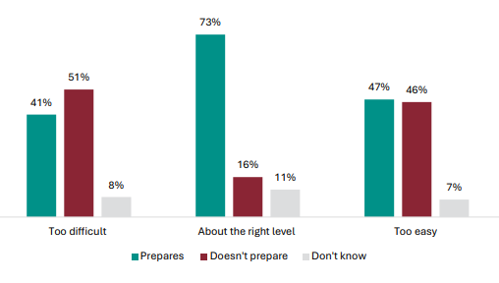

Finding 8: NCEA Level 1 isn’t always preparing students with the knowledge they need for NCEA Level 2.

Area 4: Is NCEA Level 1 motivating and manageable for students?

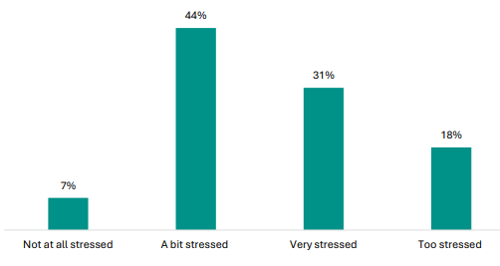

We looked at the extent to which NCEA Level 1 motivates students to engage in learning throughout the year and to achieve as well as they can, and whether their overall assessment workloads are manageable.

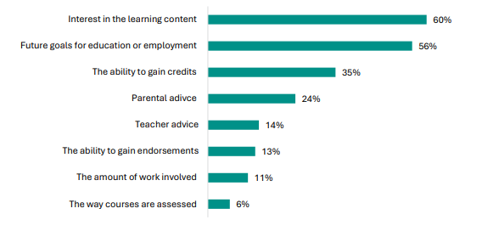

Finding 9: NCEA Level 1 is not motivating all students to achieve as well as they can, and some students disengage early.

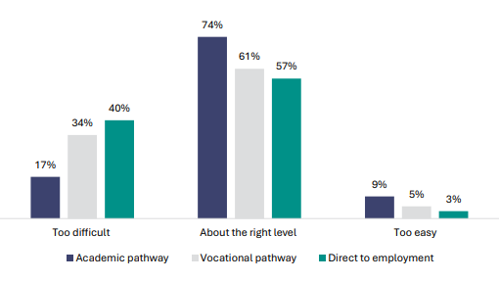

Finding 10: NCEA Level 1 is manageable, but not stretching the more academically able students.

Area 5: Is NCEA Level 1 working for all students?

All students should have the opportunity to achieve. We looked at how well NCEA Level 1 is working for a range of students.

Finding 11: Some aspects for NCEA Level 1 aren’t working as well for Māori students, Pacific students, and students who qualify for Special Assessment Conditions (SACs).

Area 6: Is NCEA Level 1 manageable for schools?

We looked at whether teachers and leaders are finding NCEA Level 1 manageable, both in terms of preparing for and teaching the new achievement standards and administering assessments.

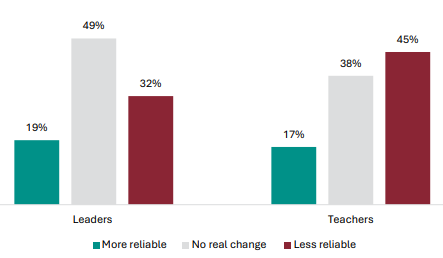

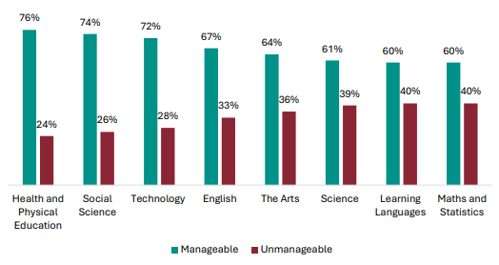

Finding 12: Schools are finding the new NCEA Level 1 unmanageable in its first year, and it is likely that some issues will remain after the initial change.

Area 7: What are the implications of the co-requisite?

From 2024, NCEA certification at any of the three levels, requires a 20-credit co-requisite. Currently, this can be achieved by participating in the co-requisite assessments, known as Common Assessment Activities (CAAs), or by gaining 10 literacy and 10 numeracy credits from a list of approved standards. We looked at how this change is being delivered and the impacts.

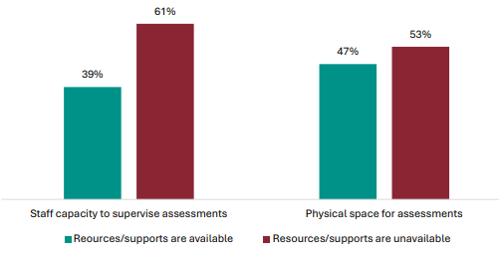

Finding 13: Schools value the standardisation introduced by the co-requisite, but administering the assessments is logistically challenging.

Area 8: What has and hasn’t worked from implementation – what lessons have we learnt?

Change is always challenging. We looked at usefulness of resources and supports to help schools implement the changes to NCEA Level 1 and what can make it more manageable.

Finding 14: Implementation has not gone well.

Recommendations

Based on these key findings, ERO has identified four areas of recommendations:

Area 1: Quick changes

In order to improve the fairness and reliability of NCEA Level 1 and help schools to administer external assessments, ERO recommends the following quick changes.

Recommendation 1: Replace the submitted reports.

Recommendation 2: Resource schools for the additional external assessments.

Recommendation 3: Extend the transitional period for the literacy and numeracy requirements.

Recommendation 4: Rethink how external assessment is conducted for practical knowledge and skills.

Recommendation 5: Review achievement standards, where there’s concern, so that credits are an equal amount of work and difficulty.

Recommendation 6: Revisit whether achievement standards for some subjects are too literacy-heavy.

Recommendation 7: Provide results more quickly for the co-requisite.

Recommendation 8: Provide schools with exemplars for the full range of assessment formats.

Recommendation 9: Provide resources that schools can use to help parents and whānau understand the requirements for NCEA Level 1.

In order to allow schools to make the right choices for their students in the short-term. NCEA Level 1 should remain optional.

Recommendation 10: Keep NCEA Level 1 optional for now.

Area 2: Reform

To improve the quality and credibility of the qualification longer term, ERO recommends reform.

Recommendation 11: Decide on the purpose of NCEA Level 1 and revise the model to fit the purpose. The three main options are:

- Drop it entirely.

- Target it as a foundational qualification.

- Make NCEA Level 1 more challenging to better prepare students for NCEA Level 2 and stretch the most academically able.

Whichever model is adopted, to improve the reliability, fairness, and inclusivity, reform should also involve the following.

Recommendation 12: Reduce flexibility in the system.

Recommendation 13: Reduce variability between credits.

Recommendation 14: Retain fewer, larger standards to support deeper learning and reduce flexibility in the system but put more weight on assessments later in the year.

Recommendation 15: Strengthen vocational options and develop better vocational pathways.

Area 3: Implications for NCEA Levels 2 and 3

Some issues at NCEA Level 1 will also apply at NCEA Levels 2 and 3. ERO recommends changes at NCEA Levels 2 and 3:

Recommendation 16: Reduce flexibility in the system.

Recommendation 17: Decide on the model for NCEA across all three Levels.

Area 4: Lessons for implementation of future changes

Implementation of NCEA Level 1 has lessons for implementing further changes:

Recommendation 18: Sequence changes and signpost earlier.

Recommendation 19: Provide information, supports, and resources to schools earlier.

Recommendation 20: Involve experts in the changes.

Recommendation 21: Coordinate information and resources better.

Conclusion

Qualifications are important to life outcomes. These findings tell us that NCEA Level 1 still isn’t a fair and reliable measure of student knowledge and skills. Due to remaining flexibility in the system, the difficulty and the amount of work differ by school and learning area and students sometimes miss out on important subject knowledge. To improve the quality and credibility of NCEA, it is critically important to act on these findings and recommendations.

About this report

NCEA Level 1 changes came into effect in 2024. The Education Review Office (ERO), commissioned by the Minister of Education, wanted to know how the implementation is going, and lessons we can learn from the early stages of implementation, to inform future changes to NCEA Level 1, NCEA Level 2, and NCEA Level 3.

What we looked at

National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) Level 1 is the first level of the three-level secondary school qualification. Each level of NCEA certification can be achieved independently of the others and all are optional, including NCEA Level 1.

A review of all three levels of the NCEA qualification was undertaken in 2018 and, from this, changes to all three levels were proposed. NCEA Level 1 is the first to undergo the proposed changes, which were piloted from 2021 to 2023 and were to be fully implemented at schools from the start of 2024.

ERO was commissioned to undertake a review of NCEA Level 1 to look at how implementation is working and the impact on students and schools so far. We set out to answer the following questions:

- Is NCEA Level 1 valued?

- Is NCEA Level 1 now a fair and reliable measure of knowledge and skills?

- Is NCEA Level 1 helping students make good choices and providing them with the knowledge they need for their future?

- Is NCEA Level 1 motivating and manageable for students?

- What are the implications of the co-requisite?

- How well NCEA level 1 is working for all students?

- Is NCEA Level 1 manageable for schools?

- What has and hasn’t worked from implementation – lessons learnt?

What we did

The findings of our review are evidenced by a range of data and analysis

We have taken a robust, mixed methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

Over 6,000 survey responses from:

1,435 teachers

254 leaders

2,376 Year 11 students

1,675 parents and whānau of Year 11 students

102 employers of school leavers

290 schools in follow up survey

Interviews and focus groups with over 300 participants including:

106 teachers

67 leaders

119 Year 11 students

10 parents and whānau of Year 11 students

8 subject associations

1 employer (of school leavers)

2 secondary tertiary providers

5 school boards

5 other expert informants

Site visits to:

21 secondary schools across the country

Data from:

A review of the international and Aotearoa New Zealand literature

Analysis of administrative data from NZQA, the Ministry of Education, and the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI)

Our data represents the diversity of schools and students in Aotearoa New Zealand.

We collected data in late Term 2, 2024, when schools offering NCEA Level 1 had completed internal assessments for at least one achievement standard in each subject and had experienced at least one Common Assessment Activities (CAAs) event for reading, writing, and numeracy. Teaching and learning for the externally assessed standards scheduled in Term 3 and 4 had most likely not begun.

For our schools visits and surveys, we collected data across a range of state and state-integrated, secondary, and composite schools, across key characteristics, including:

- major urban, large urban, minor urban, and rural

- school size – very large, large, medium, and small

- schools from low to high socio-economic communities.

Student and parent survey responses were collected to be representative of different ethnicities, genders and regions of Aotearoa New Zealand.

We examined teacher responses by the nine New Zealand Curriculum learning areas. We had sufficient data for robust comparisons between them, except for Te Reo Māori, which involves a smaller group of teachers.

- Arts

- English

- Health and Physical Education

- Learning Languages

- Mathematics and Statistics

- Science

- Social Sciences

- Te Reo Māori

- Technology

More information about our methodology can be found in Appendix 1. This includes details about the schools that responded to our surveys and participated in our in-depth case study visits. It also includes information about response rates and characteristics for all survey participant groups, including leaders, teachers, students, parents and whānau, and employers.

Report structure

This report is divided into 10 chapters.

Chapter 1 provides the background to what matters for qualifications and what NCEA is, including the context and timeline for the NCEA Level 1 changes. This chapter also provides the international evidence on why qualifications matter and what makes them high-quality.

Chapter 2 sets out the extent schools are now offering NCEA Level 1 and why following the implementation of the changes to NCEA Level 1.

Chapter 3 looks at how fair and reliable a measure of student knowledge and skills NCEA Level 1 is. Identifying the key issues and concerns raised about variability across schools, subjects, and form of assessment.

Chapter 4 looks at how NCEA Level 1 is helping students make good choices and preparing them for their future.

Chapter 5 describes how motivating and manageable the NCEA Level 1 changes have been for students and looks at the impact of the changes on students.

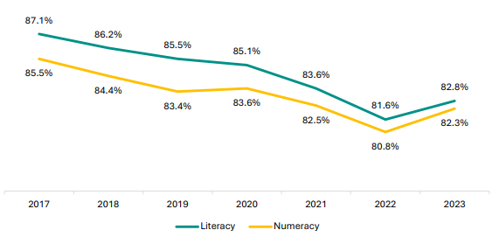

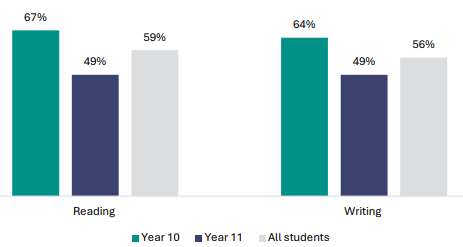

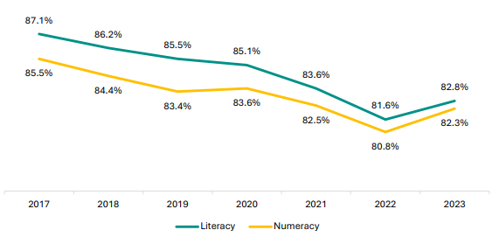

Chapter 6 describes the literacy and numeracy NCEA co-requisite in greater detail, the implementation of these common assessment activities administered by schools, and the achievement patterns so far.

Chapter 7 looks at how well NCEA Level 1 is working across learners, looking at how it is working for Māori students, Pacific students, students on vocational pathways, and students who qualify for Special Assessment Conditions (SACs), as well as transient students.

Chapter 8 describes how manageable NCEA Level 1 has been for schools so far. In particular, it reports on the administrative capacity and staff capability in schools to undertake the full implementation.

Chapter 9 looks at what has and what hasn’t worked with the implementation of NCEA Level 1 so far, with a focus on resources and support from the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), NZQA, and subject associations.

Chapter 10 sets out our key findings and recommendations for the ongoing implementation of NCEA Level 1 and informs the updates to NCEA Level 2 and NCEA Level 3.

NCEA Level 1 changes came into effect in 2024. The Education Review Office (ERO), commissioned by the Minister of Education, wanted to know how the implementation is going, and lessons we can learn from the early stages of implementation, to inform future changes to NCEA Level 1, NCEA Level 2, and NCEA Level 3.

What we looked at

National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) Level 1 is the first level of the three-level secondary school qualification. Each level of NCEA certification can be achieved independently of the others and all are optional, including NCEA Level 1.

A review of all three levels of the NCEA qualification was undertaken in 2018 and, from this, changes to all three levels were proposed. NCEA Level 1 is the first to undergo the proposed changes, which were piloted from 2021 to 2023 and were to be fully implemented at schools from the start of 2024.

ERO was commissioned to undertake a review of NCEA Level 1 to look at how implementation is working and the impact on students and schools so far. We set out to answer the following questions:

- Is NCEA Level 1 valued?

- Is NCEA Level 1 now a fair and reliable measure of knowledge and skills?

- Is NCEA Level 1 helping students make good choices and providing them with the knowledge they need for their future?

- Is NCEA Level 1 motivating and manageable for students?

- What are the implications of the co-requisite?

- How well NCEA level 1 is working for all students?

- Is NCEA Level 1 manageable for schools?

- What has and hasn’t worked from implementation – lessons learnt?

What we did

The findings of our review are evidenced by a range of data and analysis

We have taken a robust, mixed methods approach to deliver breadth and depth, including:

Over 6,000 survey responses from:

1,435 teachers

254 leaders

2,376 Year 11 students

1,675 parents and whānau of Year 11 students

102 employers of school leavers

290 schools in follow up survey

Interviews and focus groups with over 300 participants including:

106 teachers

67 leaders

119 Year 11 students

10 parents and whānau of Year 11 students

8 subject associations

1 employer (of school leavers)

2 secondary tertiary providers

5 school boards

5 other expert informants

Site visits to:

21 secondary schools across the country

Data from:

A review of the international and Aotearoa New Zealand literature

Analysis of administrative data from NZQA, the Ministry of Education, and the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI)

Our data represents the diversity of schools and students in Aotearoa New Zealand.

We collected data in late Term 2, 2024, when schools offering NCEA Level 1 had completed internal assessments for at least one achievement standard in each subject and had experienced at least one Common Assessment Activities (CAAs) event for reading, writing, and numeracy. Teaching and learning for the externally assessed standards scheduled in Term 3 and 4 had most likely not begun.

For our schools visits and surveys, we collected data across a range of state and state-integrated, secondary, and composite schools, across key characteristics, including:

- major urban, large urban, minor urban, and rural

- school size – very large, large, medium, and small

- schools from low to high socio-economic communities.

Student and parent survey responses were collected to be representative of different ethnicities, genders and regions of Aotearoa New Zealand.

We examined teacher responses by the nine New Zealand Curriculum learning areas. We had sufficient data for robust comparisons between them, except for Te Reo Māori, which involves a smaller group of teachers.

- Arts

- English

- Health and Physical Education

- Learning Languages

- Mathematics and Statistics

- Science

- Social Sciences

- Te Reo Māori

- Technology

More information about our methodology can be found in Appendix 1. This includes details about the schools that responded to our surveys and participated in our in-depth case study visits. It also includes information about response rates and characteristics for all survey participant groups, including leaders, teachers, students, parents and whānau, and employers.

Report structure

This report is divided into 10 chapters.

Chapter 1 provides the background to what matters for qualifications and what NCEA is, including the context and timeline for the NCEA Level 1 changes. This chapter also provides the international evidence on why qualifications matter and what makes them high-quality.

Chapter 2 sets out the extent schools are now offering NCEA Level 1 and why following the implementation of the changes to NCEA Level 1.

Chapter 3 looks at how fair and reliable a measure of student knowledge and skills NCEA Level 1 is. Identifying the key issues and concerns raised about variability across schools, subjects, and form of assessment.

Chapter 4 looks at how NCEA Level 1 is helping students make good choices and preparing them for their future.

Chapter 5 describes how motivating and manageable the NCEA Level 1 changes have been for students and looks at the impact of the changes on students.

Chapter 6 describes the literacy and numeracy NCEA co-requisite in greater detail, the implementation of these common assessment activities administered by schools, and the achievement patterns so far.

Chapter 7 looks at how well NCEA Level 1 is working across learners, looking at how it is working for Māori students, Pacific students, students on vocational pathways, and students who qualify for Special Assessment Conditions (SACs), as well as transient students.

Chapter 8 describes how manageable NCEA Level 1 has been for schools so far. In particular, it reports on the administrative capacity and staff capability in schools to undertake the full implementation.

Chapter 9 looks at what has and what hasn’t worked with the implementation of NCEA Level 1 so far, with a focus on resources and support from the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), NZQA, and subject associations.

Chapter 10 sets out our key findings and recommendations for the ongoing implementation of NCEA Level 1 and informs the updates to NCEA Level 2 and NCEA Level 3.

Chapter 1: Background – what matters for qualifications and what is NCEA?

Qualifications usually lead to a range of positive life outcomes, but it is important that they are of high quality. A high-quality qualification should be fair and reliable, motivating and manageable, and meet the needs of a diverse range of students. It should also support future pathways.

In this chapter we describe why qualifications are important, why NCEA is changing, what makes a strong qualification, and how different jurisdictions approach qualifications at age 16.

What we looked at

It is important that our main secondary school qualification in Aotearoa New Zealand is working the way that it should. Our main secondary school qualification, introduced in 2002, is the National Certificate of Educational Achievement, or NCEA. We looked at the important elements of qualifications, the background of NCEA and the recent changes that are being implemented.

This chapter sets out findings on:

- why qualifications matter

- what makes a high-quality qualification

- NCEA and recent changes

- what makes NCEA unique to Aotearoa New Zealand.

1) Why qualifications matter

Leaving school with higher qualifications leads to a range of more positive life outcomes. This includes higher incomes and better chances of employment.

Young people who leave school with NCEA Level 1 and do not go on to achieve any further qualifications, compared to those who leave without NCEA Level 1 and never achieve a qualification, are:

- 2 times more likely to have employment income at age 29-34 (72 percent compared to 58 percent)

- 9 times as likely (or one-tenth less likely) to receive a main benefit since leaving school (72 percent compared to 83 percent)

- 8 times as likely (or one-fifth less likely) to have committed an offence (48 percent compared to 58 percent)

- 0.4 times as likely (or three-fifths less likely) to have served a custodial sentence (6 percent compared to what 14 percent).

2) What makes a high-quality qualification?

A high-quality qualification should be valued both by teachers and students, and by those who rely on the qualification to make decisions (e.g., employers and further education providers). They should also hold international credibility to support potential future pathways. Evidence shows qualifications are valued when they do the following, set out below.

Are fair and reliable

- Are a fair and reliable measure of a student’s knowledge and skills of the curriculum – assessments should allow students a fair chance to show what they know and can do, and qualifications should accurately and consistently reflect student performance.

Support future pathways

- Support students to make good choices and prepare them with the knowledge and skills needed for their future. This is more likely when qualifications are coherent and cumulative – which means what is being assessed promotes learning of key knowledge and skills for each subject – which should build sequentially so students don’t experience gaps and jumps between levels.

Motivate students and provide choice

- Are motivating and manageable for students – students are motivated to engage in learning and achieve as well as they can, and to make the right choices for them in terms of their preferred pathways and career. Also, the workload for learning and assessments should be realistic and not unreasonably stressful.

Meet the needs of diverse students

- Meet the needs of a diverse range of learners – the learning and assessments should be both accessible to all learners and challenging enough to stretch the most able students.

Manageable for schools

- Are deliverable for schools – teachers and leaders should find delivering the qualification manageable, both in terms of preparing students for and administering assessments.

This review looked at whether the changes to NCEA Level 1 were implemented in a way that strengthened the qualification in line with the above criteria.

What is the purpose of a school qualification at age 16?

Secondary education qualifications should support students to further develop their knowledge and skills for further learning and the labour market. Qualifications can act as a key tool to secure good quality and meaningful teaching and learning for all students.

A common feature among many OECD countries with high graduation rates from school is that they have an upper secondary qualification which serves as a common minimum requirement for further study or employment.

Depending on the country and system, national qualifications at age 16 can serve a combination of the following purposes:

- to support active learning – recognising the role assessment can play in the learning process

- to provide a record of learning to support students onto their next pathway (this is particularly important for students who choose to leave school at 16)

- to assess if students have a broad foundational knowledge, preparing students for further qualifications

- to provide a benchmark in key areas such as literacy/te reo matatini and numeracy/pāngarau

- for school accountability purposes, to measure student outcomes and school performance

- to provide students and parents and whānau with insights into learning that supports informed decisions about future pathways.

What do qualifications look like across OECD countries?

Different jurisdictions take a varied approach to national qualifications. Table 1 summarises how a selection of countries approach qualifications at age 16.

Table 1: International comparison of qualifications at age 16

Note: Where jurisdictions do not have qualifications at 16, the table includes characteristics of the broader qualification system.

3) NCEA and recent changes

What is NCEA?

The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main secondary school qualification. The Ministry of Education is responsible for the design of NCEA. The New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) administers NCEA.

NCEA Levels

NCEA has three levels in which you can gain a qualification certificate in:

- NCEA Level 1 – usually in Year 11

- NCEA Level 2 – usually in Year 12

- NCEA Level 3 – usually in Year 13

Courses, subjects, and standards for NCEA Level 1

Students will usually take five or six courses across the school year, which consist of several ‘achievement standards’ that are graded (Achieved, Merit, Excellence) and/or ‘unit standards’ that are assessed as either Achieved or Not Achieved. There are two types of assessments:

- Internal Assessments – assessments that takes place throughout the year, assessed by teachers in school.

- External Assessments – national examinations or the submission of a portfolio of work completed at school or with the school and a tertiary organisation, assessed by NZQA.

For NCEA Level 1, achievement standards are typically worth five credits. Unit standards are typically smaller and are worth varying credit values.

Subjects each have four achievement standards, including two that are internally assessed and two that are externally assessed. Schools often design courses around subjects, but they don’t have to. Schools can mix achievement and unit standards from across a range of subjects.

Credits and grading

To achieve an NCEA qualification, a student needs 60 credits at the relevant Level or above. Additionally, students require a 20-credit literacy (or te reo matatini) and numeracy (or pāngarau) co-requisite, which can be awarded any Level of NCEA (this is separate to credits earned in the subjects of Maths and English and the co-requisite is Achieved/Not Achieved).

The co-requisite is a one-off requirement. Up until the end of 2027, while NCEA is transitioning to its new form, students will also be able to achieve the NCEA co-requisite through an approved list of literacy and numeracy-rich achievement standards.

Each NCEA Level certificate can be endorsed with Merit or Excellence. Certificate endorsements require 50 credits from the relevant grade or higher from any standards completed at the right level within one school year. For example, a student may have 75 total credits, 45 at Merit level, 20 at Excellence level, and 10 at Achieved level, and because they have 65 credits at the Merit level or higher, they will obtain NCEA Level 1 endorsed with Merit.

A student may also receive endorsement in a subject by obtaining at least 14 credits from standards in that subject at the relevant level or higher.

Why was NCEA introduced?

NCEA was introduced between 2002 and 2004 (Level 1 – Level 3), replacing the New Zealand School Certificate. NCEA was introduced to:

- provide a fuller picture of a student’s knowledge and skills through continuous assessment throughout the year – any student who demonstrates the required knowledge and skills of a standard achieves the NCEA credit

- recognise vocational knowledge and skills previously not recognised

- allow more students to gain qualifications – since NCEA was introduced, more students are leaving school with qualifications.

NCEA was designed to be flexible and inclusive so that it recognises and caters to the diverse needs of students and their different learning pathways.

Why is NCEA changing?

A review of NCEA was launched in 2018. The aim of this review was to ensure that NCEA is a robust qualification that is valued by students, their parents and whānau, employers, tertiary education organisations, iwi, and communities. More about this review can found at Appendix 2.

What changes have been implemented to NCEA Level 1?

The NCEA Change Programme made seven changes to NCEA Level 1, set out in the table below.

Table 2: Changes to NCEA Level 1

What is happening at NCEA Levels 2 and 3?

Further changes to NCEA, particularly for Levels 2 and 3, have been delayed by two years to ensure a curriculum review and refresh for Years 11-13 is completed first. NCEA Level 2 changes will be implemented by 2028, not in 2026 as previously planned. NCEA Level 3 will be fully implemented by 2029, not in 2027.

4) What makes NCEA unique to Aotearoa New Zealand?

Table 1 shows how NCEA differs from the qualifications used in some of the other jurisdictions that we looked at. Key features of NCEA that set it apart are set out below.

- NCEA involves three years of distinct qualifications. This was unique from the countries we looked at which typically had one or two years of formal assessment throughout senior secondary.

- Schools and students can design their own courses, mixing achievement standards and unit standards from different subjects. This is unique from many other international qualifications where courses have a more standardised structure, and vocational and academic pathways are split or unavailable at this stage (such as GCSEs in the UK).

- NCEA achievement standards are assessed using internal and external modes of assessment and a wider variety of assessment methods are used, including research inquiry, portfolio, and examination.

- NCEA assessment formats place a higher degree of trust in schools and teachers as they involve strong school autonomy in implementing evaluation and assessment. For many assessments, the responsibility for overall judgements against internally assessed standards largely sits with teachers.

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach to qualifications has been designed to reflect the Crown’s obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. NCEA Level 1 has been designed to give effect to mana ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori (mana ōrite) with achievement standards that allow students to use Māori knowledge as evidence where appropriate. Some other jurisdictions, such as British Columbia, also incorporate an indigenous-focused graduation requirement.

Conclusion

Qualifications are important for future life outcomes. Students who leave school with higher qualifications are more likely to be employed, earn more, spend less time receiving benefits, and are less likely to commit an offence.

NCEA is New Zealand’s qualification in secondary schools. It is unique as it involves three years, schools can design their own courses and uses a wide range of assessment formats.

The next chapter sets out what schools are currently doing in Year 11, and how well NCEA Level 1 is delivering for students.

Qualifications usually lead to a range of positive life outcomes, but it is important that they are of high quality. A high-quality qualification should be fair and reliable, motivating and manageable, and meet the needs of a diverse range of students. It should also support future pathways.

In this chapter we describe why qualifications are important, why NCEA is changing, what makes a strong qualification, and how different jurisdictions approach qualifications at age 16.

What we looked at

It is important that our main secondary school qualification in Aotearoa New Zealand is working the way that it should. Our main secondary school qualification, introduced in 2002, is the National Certificate of Educational Achievement, or NCEA. We looked at the important elements of qualifications, the background of NCEA and the recent changes that are being implemented.

This chapter sets out findings on:

- why qualifications matter

- what makes a high-quality qualification

- NCEA and recent changes

- what makes NCEA unique to Aotearoa New Zealand.

1) Why qualifications matter

Leaving school with higher qualifications leads to a range of more positive life outcomes. This includes higher incomes and better chances of employment.

Young people who leave school with NCEA Level 1 and do not go on to achieve any further qualifications, compared to those who leave without NCEA Level 1 and never achieve a qualification, are:

- 2 times more likely to have employment income at age 29-34 (72 percent compared to 58 percent)

- 9 times as likely (or one-tenth less likely) to receive a main benefit since leaving school (72 percent compared to 83 percent)

- 8 times as likely (or one-fifth less likely) to have committed an offence (48 percent compared to 58 percent)

- 0.4 times as likely (or three-fifths less likely) to have served a custodial sentence (6 percent compared to what 14 percent).

2) What makes a high-quality qualification?

A high-quality qualification should be valued both by teachers and students, and by those who rely on the qualification to make decisions (e.g., employers and further education providers). They should also hold international credibility to support potential future pathways. Evidence shows qualifications are valued when they do the following, set out below.

Are fair and reliable

- Are a fair and reliable measure of a student’s knowledge and skills of the curriculum – assessments should allow students a fair chance to show what they know and can do, and qualifications should accurately and consistently reflect student performance.

Support future pathways

- Support students to make good choices and prepare them with the knowledge and skills needed for their future. This is more likely when qualifications are coherent and cumulative – which means what is being assessed promotes learning of key knowledge and skills for each subject – which should build sequentially so students don’t experience gaps and jumps between levels.

Motivate students and provide choice

- Are motivating and manageable for students – students are motivated to engage in learning and achieve as well as they can, and to make the right choices for them in terms of their preferred pathways and career. Also, the workload for learning and assessments should be realistic and not unreasonably stressful.

Meet the needs of diverse students

- Meet the needs of a diverse range of learners – the learning and assessments should be both accessible to all learners and challenging enough to stretch the most able students.

Manageable for schools

- Are deliverable for schools – teachers and leaders should find delivering the qualification manageable, both in terms of preparing students for and administering assessments.

This review looked at whether the changes to NCEA Level 1 were implemented in a way that strengthened the qualification in line with the above criteria.

What is the purpose of a school qualification at age 16?

Secondary education qualifications should support students to further develop their knowledge and skills for further learning and the labour market. Qualifications can act as a key tool to secure good quality and meaningful teaching and learning for all students.

A common feature among many OECD countries with high graduation rates from school is that they have an upper secondary qualification which serves as a common minimum requirement for further study or employment.

Depending on the country and system, national qualifications at age 16 can serve a combination of the following purposes:

- to support active learning – recognising the role assessment can play in the learning process

- to provide a record of learning to support students onto their next pathway (this is particularly important for students who choose to leave school at 16)

- to assess if students have a broad foundational knowledge, preparing students for further qualifications

- to provide a benchmark in key areas such as literacy/te reo matatini and numeracy/pāngarau

- for school accountability purposes, to measure student outcomes and school performance

- to provide students and parents and whānau with insights into learning that supports informed decisions about future pathways.

What do qualifications look like across OECD countries?

Different jurisdictions take a varied approach to national qualifications. Table 1 summarises how a selection of countries approach qualifications at age 16.

Table 1: International comparison of qualifications at age 16

Note: Where jurisdictions do not have qualifications at 16, the table includes characteristics of the broader qualification system.

3) NCEA and recent changes

What is NCEA?

The National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main secondary school qualification. The Ministry of Education is responsible for the design of NCEA. The New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) administers NCEA.

NCEA Levels

NCEA has three levels in which you can gain a qualification certificate in:

- NCEA Level 1 – usually in Year 11

- NCEA Level 2 – usually in Year 12

- NCEA Level 3 – usually in Year 13

Courses, subjects, and standards for NCEA Level 1

Students will usually take five or six courses across the school year, which consist of several ‘achievement standards’ that are graded (Achieved, Merit, Excellence) and/or ‘unit standards’ that are assessed as either Achieved or Not Achieved. There are two types of assessments:

- Internal Assessments – assessments that takes place throughout the year, assessed by teachers in school.

- External Assessments – national examinations or the submission of a portfolio of work completed at school or with the school and a tertiary organisation, assessed by NZQA.

For NCEA Level 1, achievement standards are typically worth five credits. Unit standards are typically smaller and are worth varying credit values.

Subjects each have four achievement standards, including two that are internally assessed and two that are externally assessed. Schools often design courses around subjects, but they don’t have to. Schools can mix achievement and unit standards from across a range of subjects.

Credits and grading

To achieve an NCEA qualification, a student needs 60 credits at the relevant Level or above. Additionally, students require a 20-credit literacy (or te reo matatini) and numeracy (or pāngarau) co-requisite, which can be awarded any Level of NCEA (this is separate to credits earned in the subjects of Maths and English and the co-requisite is Achieved/Not Achieved).

The co-requisite is a one-off requirement. Up until the end of 2027, while NCEA is transitioning to its new form, students will also be able to achieve the NCEA co-requisite through an approved list of literacy and numeracy-rich achievement standards.

Each NCEA Level certificate can be endorsed with Merit or Excellence. Certificate endorsements require 50 credits from the relevant grade or higher from any standards completed at the right level within one school year. For example, a student may have 75 total credits, 45 at Merit level, 20 at Excellence level, and 10 at Achieved level, and because they have 65 credits at the Merit level or higher, they will obtain NCEA Level 1 endorsed with Merit.

A student may also receive endorsement in a subject by obtaining at least 14 credits from standards in that subject at the relevant level or higher.

Why was NCEA introduced?

NCEA was introduced between 2002 and 2004 (Level 1 – Level 3), replacing the New Zealand School Certificate. NCEA was introduced to:

- provide a fuller picture of a student’s knowledge and skills through continuous assessment throughout the year – any student who demonstrates the required knowledge and skills of a standard achieves the NCEA credit

- recognise vocational knowledge and skills previously not recognised

- allow more students to gain qualifications – since NCEA was introduced, more students are leaving school with qualifications.

NCEA was designed to be flexible and inclusive so that it recognises and caters to the diverse needs of students and their different learning pathways.

Why is NCEA changing?

A review of NCEA was launched in 2018. The aim of this review was to ensure that NCEA is a robust qualification that is valued by students, their parents and whānau, employers, tertiary education organisations, iwi, and communities. More about this review can found at Appendix 2.

What changes have been implemented to NCEA Level 1?

The NCEA Change Programme made seven changes to NCEA Level 1, set out in the table below.

Table 2: Changes to NCEA Level 1

What is happening at NCEA Levels 2 and 3?

Further changes to NCEA, particularly for Levels 2 and 3, have been delayed by two years to ensure a curriculum review and refresh for Years 11-13 is completed first. NCEA Level 2 changes will be implemented by 2028, not in 2026 as previously planned. NCEA Level 3 will be fully implemented by 2029, not in 2027.

4) What makes NCEA unique to Aotearoa New Zealand?

Table 1 shows how NCEA differs from the qualifications used in some of the other jurisdictions that we looked at. Key features of NCEA that set it apart are set out below.

- NCEA involves three years of distinct qualifications. This was unique from the countries we looked at which typically had one or two years of formal assessment throughout senior secondary.

- Schools and students can design their own courses, mixing achievement standards and unit standards from different subjects. This is unique from many other international qualifications where courses have a more standardised structure, and vocational and academic pathways are split or unavailable at this stage (such as GCSEs in the UK).

- NCEA achievement standards are assessed using internal and external modes of assessment and a wider variety of assessment methods are used, including research inquiry, portfolio, and examination.

- NCEA assessment formats place a higher degree of trust in schools and teachers as they involve strong school autonomy in implementing evaluation and assessment. For many assessments, the responsibility for overall judgements against internally assessed standards largely sits with teachers.

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach to qualifications has been designed to reflect the Crown’s obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. NCEA Level 1 has been designed to give effect to mana ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori (mana ōrite) with achievement standards that allow students to use Māori knowledge as evidence where appropriate. Some other jurisdictions, such as British Columbia, also incorporate an indigenous-focused graduation requirement.

Conclusion

Qualifications are important for future life outcomes. Students who leave school with higher qualifications are more likely to be employed, earn more, spend less time receiving benefits, and are less likely to commit an offence.

NCEA is New Zealand’s qualification in secondary schools. It is unique as it involves three years, schools can design their own courses and uses a wide range of assessment formats.

The next chapter sets out what schools are currently doing in Year 11, and how well NCEA Level 1 is delivering for students.

Chapter 2: Are schools now offering NCEA Level 1 and why?

NCEA Level 1 is voluntary and there is a lot of flexibility in how it is offered. An increasing number of schools aren’t offering the full NCEA Level 1 qualification. Schools in high socio-economic communities are least likely to offer it. Schools in low to moderate socio-economic communities value it as an ‘exit qualification’. Students and parents and whānau mainly value NCEA Level 1 as a stepping stone to NCEA Level 2. Employers often value other skills and attributes over NCEA Level 1 when recruiting school leavers.

In this chapter, we set out what schools are offering in Year 11, why some schools opt out of NCEA Level 1, and how many Year 11 students are attempting the co-requisite. We also look at how valued NCEA Level 1 is by students, parents and whānau, and employers.

What we looked at

We looked at what is happening at NCEA Level 1 following the changes, including the extent to which schools are offering the full qualification and what informs their decision. We examined what students are covering in their NCEA Level 1 courses and how they are being assessed. We also looked at the extent to which students are doing the co-requisite in Year 11.

We looked at how much and why schools, students, and parents and whānau value NCEA Level 1. Although the impacts of the changes haven’t flowed through to the workplace yet, we also asked whether employers value NCEA Level 1 based on their experience of employees who have the qualification compared to those who don’t.

This chapter sets out findings on:

- the extent to which schools are offering NCEA Level 1 and why

- the types of standards and assessments students are doing

- the extent to which Year 11 students are doing the co-requisite

- if NCEA Level 1 is valued by parents and whānau

- if NCEA Level 1 is valued by students

- if NCEA Level 1 is valued by employers.

What we found: an overview

NCEA Level 1 remains optional. An increasing number of schools, mainly schools in high socio-economic areas, are opting out of offering it.

- NCEA Level 1 remains voluntary. Most schools offer it, but there is a group of schools that don’t. In 2024, one in eight schools (13 percent) aren’t offering it (87 percent are). For 2025, more schools (17 percent) plan not to offer it, and 10 percent are still deciding (73 percent of schools do plan to offer it).

- Schools in high socio-economic communities with higher NCEA achievement are least likely to offer NCEA Level 1. Only three in five schools (60 percent) offered it in 2024. They are opting out to better prepare students for Years 12 and 13 and to reduce assessment burn-out. Schools in low to medium socio-economic communities are more likely to offer NCEA Level 1. They value it as an ‘exit qualification’ for students who leave at the end of Year In 2023, 10 percent of students left at the end of Year 11, and one in five (21 percent) of these students had achieved NCEA Level 1.

Flexibility remains for schools to design their NCEA Level 1 courses, leading to variation in course content and assessment.

- There is variation in how schools are designing their courses – only one in three schools (32 percent) are typically offering all four subject achievement standards. Just over a third (68 percent) are typically offering three. Eighty-three percent of leaders report their school offers unit standards in at least one or more of their courses. Schools offering unit standards tend to serve lower socio-economic communities.

- Students are entered into more external assessments than before, but we don’t know yet how entries will translate in completions. Historically, the non-completion rate for external assessments is 20 percent, compared to only 3 percent for internal assessments.

The co-requisite is mainly being offered to Year 10 students.

- Students at any year level can sit the co-requisite assessments, but most often students sit them in Year 10. This provides maximum opportunities for students to achieve the co-requisite but also risks disengaging students who repeatedly fail.

Students and parents and whānau mainly value NCEA Level 1 as a stepping stone to NCEA Level 2. Employers value other skills and attributes over NCEA Level 1.

- Students on an academic pathway, and their parents and whānau, value NCEA Level 1 as preparation for NCEA Level 2 because it provides study skills and exam experience, when many students haven’t done exams before.

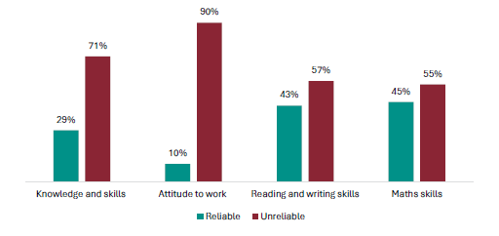

- Parents and whānau assume that employers value Level 1 as a recognised national qualification, but just over two in five employers (43 percent) don’t consider it when making recruitment decisions.

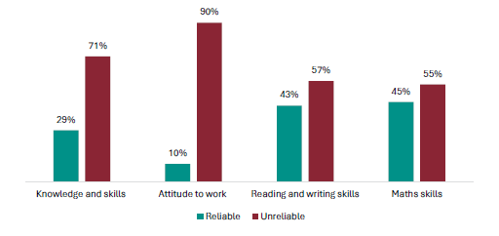

- Based on their experience of the previous NCEA Level 1 qualification, just over seven in 10 employers (71 percent) don’t think it is a reliable measure of student knowledge and skills, and nine in 10 (90 percent) don’t think it’s a reliable measure of attitude to hard work.

In the following sections we look at each of these findings in more detail.

1) To what extent are schools offering NCEA Level 1 and why?

NCEA Level 1 is voluntary. Most schools offer it, but an increasing number don’t.

Each level of NCEA certification can be achieved independently of the others. Schools can opt out of offering any level, but they are less likely to opt out of Level 2 due its role in helping students access vocational pathways; and less likely to opt out of Level 3 because it is needed for ‘University Entrance’.

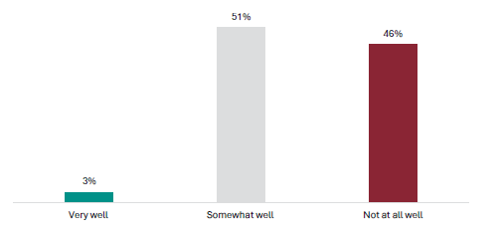

Most schools are offering NCEA Level 1 but some are opting out of offering it. In 2024, almost one in eight of the schools we surveyed (13 percent) reported that they aren’t offering the full NCEA Level 1 qualification (87 percent of schools are). In 2025 we expect this to rise to two in 10 schools or more, with just under 17 percent reporting they are planning not to offer it, and another one in 10 schools (10 percent) still considering their options.

Figure 1: Proportion of leaders who report their schools are offering NCEA Level 1 in 2024 and 2025.

Schools in low to medium socio-economic communities are more likely to offer NCEA Level 1 and schools in high socio-economic communities less likely.

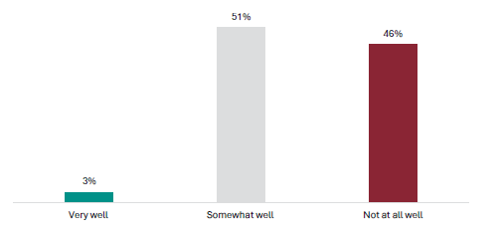

Most schools in low and medium socio-economic communities offered NCEA Level 1 this year (2024) (95 percent and 93 percent, respectively). Only three in five schools in high socio-economic communities (60 percent) offered it this year, and 40 percent opted not to.

Figure 2: Proportion of schools offering NCEA Level 1 in 2024, by socio-economic communities.

The pattern looks to be repeated in the coming year. Based on ERO’s survey at the end of Term 3 in 2024, just under four in five schools (78 percent) in low socio-economic communities plan to offer NCEA Level 1 in 2025, and 7 percent don’t plan to offer it. About one in six schools (15 percent) are still deciding.

Similarly, just over four in five schools (82 percent) in moderate socio-economic communities plan to offer Level 1 in 2025 and just over one in 10 (12 percent) don’t plan to offer it. Six percent of schools are still deciding.

By comparison, only two in five schools (43 percent) in high socio-economic communities plan to offer NCEA Level 1 in 2025, half (50 percent) don’t plan to offer it, and 7 percent are still deciding.

Figure 3: Proportion of leaders offering NCEA Level 1 qualification in 2025, by socio-economic community.

Schools in low to moderate socio-economic communities mainly value NCEA Level 1 as an ‘exit qualification’ for students who will leave at the end of Year 11.

We heard from schools in low to moderate socio-economic communities, where students are more likely to choose employment after Year 11 or 12, that they were offering NCEA Level 1 because it could be the only qualification that some of their students will get.

“Some of our students leave school and NCEA Level 1 is their only qualification. So, if we take NCEA Level 1 away, that could be problematic for some of them.” (Teacher)

These schools also tend to be offering other courses aligning with the main industries of the areas to prepare their students for work. For example, a school in an area where farming is the main sector has been offering agriculture as one of their courses to cater for students wanting to work immediately after leaving school.

In 2023, 9 percent of all school leavers achieved NCEA Level 1 as their highest qualification. Another 16 percent of school leavers left with no qualification. Further, 10 percent of Year 11 students left school at the end of the year. Just over one in five (21 percent) of these Year 11 school leavers achieved NCEA Level 1 as their highest qualification, and most (75 percent) left with no qualifications.

We heard that some schools value NCEA Level 1 for its preparation for NCEA Level 2. NCEA Level 1 introduces students to digital exams, and give students experience with formal assessments and workload management.

“[NCEA Level 1] provides a training ground for our students in Year 11, particularly in learning the language of NCEA, being comfortable in an examination environment, understanding internal and external assessments.” (Leader)

Schools are opting out of NCEA Level 1 to better prepare students for Level 2 and Level 3, reduce over-assessment, and offer other assessments.

We heard that many schools who are opting out of offering NCEA Level 1, are doing so because they have concerns about over-assessment. Schools believe three years of high-stakes national assessments is stressful for students and impacts their achievement in Level 2 and Level 3. By the time students reach Year 13 they can feel burnt out and may be less motivated or able to perform as well as they are able.

“Eighty percent of our students stay until the end of Year 13. By the time they got to the end of their journey, they are well over-assessed.” (Leader)

Some schools that are opting out of NCEA Level 1 have different strategies for their Year 11 students. We heard that some schools are offering their own Year 11 diploma or certificate, which recognises a broader range of achievements. For example, in addition to academic excellence, Year 11 accreditation will reward things like attendance, leadership, and service. Alternatively, some schools only offer the co-requisite CAAs and use Year 11 as the first of a two-year preparation for NCEA Level 2.

“We want to really focus on Year 9 to 11 as more of a cohesive, foundational learning time to set them up for the high stakes qualifications at NCEA Levels 2 and 3.” (Leader)

Schools in major urban, high socio-economic communities are also less likely to offer NCEA Level 1 is because their community wants a different qualification, such as the International Baccalaureate or Cambridge Assessment International Examinations.

“[Our students] look at the world as their next place to get education. They're looking at the States, they're looking at Europe. We've got to really open our eyes to all of that as well and offer other qualifications.” (Leader)

We heard some parents value these international qualifications more highly than NCEA for being more rigorous. Both the International Baccalaureate and the Cambridge Assessment are more structured than NCEA. Cambridge is the most highly structured, offering fewer elective subjects, and all examinations are externally assessed. On this basis, some parents think these international qualifications will prepare their children better for tertiary pathways and, in particular, will help their children access universities overseas, where these qualifications are well-recognised.

“More and more parents around me are moving their children to a school that offer International Baccalaureate. This is perceived as a better qualification. The issue is that in Wellington only private schools provide this option.” (Parent and whānau)

Some schools are ‘waiting to see’ before deciding on NCEA Level 1.

Another key reason for schools not offering NCEA Level 1 this year (and possibly next) is because they are using a ‘wait and see’ approach to see how the Level 1 changes are going in other schools, and while the uncertainty with curriculum changes and NCEA Levels 2 and 3 are resolved. While schools are largely supportive of the delay in rolling out NCEA Levels 2 and 3 changes, this extends the period of uncertainty.

“We wanted a Level 1 that backed directly into the new Level 2, but the timeline given to us about the changes between Level 1 and Level 2 is too fuzzy. […] Pausing and waiting would have been the best way.” (Leader)

2) What types of standards and assessments are students doing?

Most schools aren’t offering all four subject achievement standards.

Subjects have been designed with four achievement standards, including two that are internally assessed and two that are externally assessed (see more detail on this in Appendix 3). In implementing this design, it was intended that students would experience an equal amount of internal and external assessment, but this depends on how schools are designing courses.

Schools can choose if they want to offer all four standards and which standards to offer. This has resulted in significant variation among schools.

For schools offering the NCEA Level 1 qualification, just under a third (32 percent) are offering four achievements standards in their NCEA Level 1 courses. Just over two-thirds (68 percent) are offering three achievement standards in their courses.

Chapter 3 sets out why schools aren’t offering all four achievement standards.

Figure 4: Proportion of schools offering 2, 3, or 4 achievement standards.

Students are still doing more internal assessment but are entered into more external assessment than before.

As part of the changes, NCEA Level 1 was designed to have subjects assessed with half internal and half external assessment. However, this has not been achieved as most often the external standards are being dropped when a course is not using all four standards.

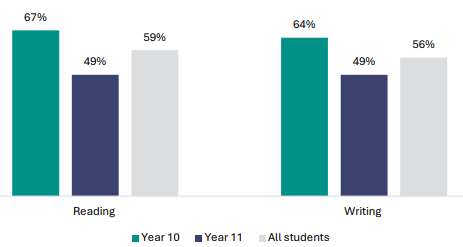

Whilst the split between internal and external assessment is not yet fifty-fifty, students are entered into more external assessment in 2024 than were in the previous three years. In 2021, 67 percent of Year 11 entries were internal standards and 33 percent were external standards. In 2024, 59 percent of Year 11 entries were internals and 41 percent were externals.

However, it is important to note that students don’t always complete every assessment they are entered for, so it won’t be clear until the end of the year how many external assessments were completed. The non-completion rate for external credits increased from 15 percent in 2019 to 23 percent in 2021 and 2022, and was 22 percent in 2023.

Entries may not translate into completions for lots of reasons, including student sickness or student choice. For example, students may decide they already have enough credits and so don’t turn up for exams on the day, or decide only to complete one of the assessments scheduled.

Figure 5: Proportion of NCEA Level 1 entries into internal and external assessments, by time.

Schools are still using unit standards.

NCEA uses unit standards and achievement standards. With achievement standards students can obtain Achieved, Achieved with Merit, Achieved with Excellence, or Not Achieved. With unit standards, students can usually obtain only Achieved or Not Achieved. Unit standards are used for assessing practical knowledge a student either knows or doesn’t know, skills they can or can’t do.