Related Insights

Explore related documents that you might be interested in.

Read Online

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank all the parents and whānau, ECE service and school teachers and leaders, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights throughout interviews, groups discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time so that others may benefit from your stories. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give generous thanks for the ECE services and schools that accommodated our research team on visits, organising time in their day for us to talk to teachers and leaders. We know your time is precious.

We also thank the many experts who have shared their understandings of oral language in the Aotearoa New Zealand context with us. Ministry of Education staff and speech-language therapists had a pivotal role in the development of these reports. We particularly acknowledge the members of our Expert Advisory Group of practitioners, academics, and sector experts, who shared their knowledge and wisdom to help guide the evaluation and make sense of emerging findings.

We acknowledge and thank all the parents and whānau, ECE service and school teachers and leaders, and others who shared their experiences, views, and insights throughout interviews, groups discussions, and surveys. We thank you for giving your time so that others may benefit from your stories. We thank you openly and whole-heartedly.

We give generous thanks for the ECE services and schools that accommodated our research team on visits, organising time in their day for us to talk to teachers and leaders. We know your time is precious.

We also thank the many experts who have shared their understandings of oral language in the Aotearoa New Zealand context with us. Ministry of Education staff and speech-language therapists had a pivotal role in the development of these reports. We particularly acknowledge the members of our Expert Advisory Group of practitioners, academics, and sector experts, who shared their knowledge and wisdom to help guide the evaluation and make sense of emerging findings.

Executive summary

Language is the foundation for children’s learning and success. Children use oral language to become good thinkers and communicators, and to develop the literacy skills they need to achieve well in school and beyond. This report draws together a range of evidence to look at how well children are developing the oral language skills they need when they start school. We also look at how early childhood education (ECE) can help children to develop these important skills.

ERO found that while most children’s oral language is developing well, there is a significant group of children who struggle, and Covid-19 has made this worse. Quality ECE makes a difference, and the evidence shows there are key teaching practices that matter. We recommend five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development.

What is oral language?

Oral language is how we use spoken words to express ideas, knowledge, and feelings. Developing oral language involves developing the skills and knowledge that go into listening and speaking. These skills are important foundations for learning how to read and write. ERO looked at eight areas of language development:

|

Gestures |

Using and adding gestures as part of communication |

|

Words |

Learning, understanding, and using a range of words |

|

Sounds |

Adding, using, and understanding sounds |

|

Social communication |

Changing their language, using words to express needs |

|

Syntax |

Combining words to form sentences |

|

Stories |

Enjoy listening to, being read to, and telling stories |

|

Grammar |

Constructing nearly correct sentences and asking questions |

|

Rhyming |

Making rhymes |

What are the early years?

ERO looked at oral language development of children aged 0 to 7 years old in ECE and new entrant classes.

What did ERO look at?

ERO drew together a wide range of established international and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence. We also surveyed and spoke to parents and whānau, ECE and new entrant teachers, ECE service leaders, and a range of sector experts to understand how well children across Aotearoa New Zealand are developing oral language skills and how well supported they are. ERO visited a selection of ECE services and new entrant classrooms across Aotearoa New Zealand to better understand children’s progress and the teaching practices that support them.

Key findings

Oral language is critical for achieving the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Finding 1: Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and delays in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind and Covid-19 has made this worse.

Finding 2: A large Aotearoa New Zealand study found 80 percent of children at age 5 are doing well, but 20 percent are struggling with oral language. ECE and new entrant teachers also report that a group of children are struggling and half of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Finding 3: Covid-19 has had a significant impact. Nearly two-thirds of teachers (59 percent of ECE teachers and 65 percent of new entrant teachers) report that Covid-19 has impacted children’s language development. Teachers told us that social communication was particularly impacted by Covid-19, particularly language skills for social communication. International studies confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on language development.

"A lot of children are not able to communicate their needs. They are difficult to understand when they speak. They are not used to having conversations." (Teacher)

Children from low socio-economic communities and boys are struggling the most.

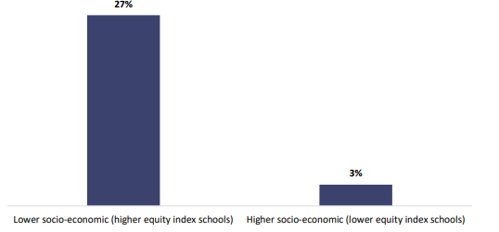

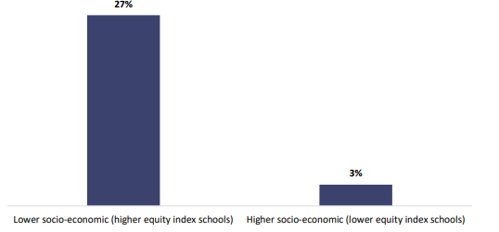

Finding 4: Evidence both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally is clear that children from lower socio-economic communities are more likely to struggle with oral language skills. We found that new entrant teachers we surveyed in schools in low socio-economic communities were nine times more likely to report children being below expected levels of oral language. Parents and whānau with lower qualifications were also more likely to report that their child has difficulty with oral language.

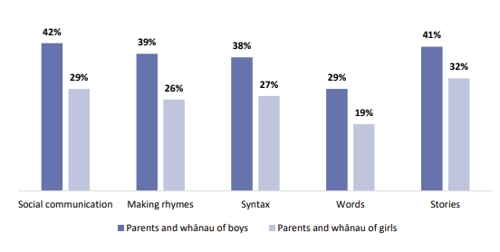

Finding 5: Both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally, boys have more difficulty developing oral language than girls. Parents and whānau we surveyed reported 70 percent of boys are not at the expected development level, compared with 56 percent of girls.

Difficulties with oral language emerge as children develop and oral language becomes more complex.

Finding 6: Teachers and parents and whānau report more concerns about children being behind as they become older and start school. For example, 56 percent of parents and whānau report their child has difficulty as a toddler (aged 18 months to 3 years old), compared to over two-thirds of parents and whānau (70 percent) reporting that their child has difficulty as a preschooler (aged 3 to 5).

Finding 7: Teachers and parents and whānau reported to us that children who are behind most often struggle with constructing sentences, telling stories, and using social communication to talk about their thoughts and feelings. For example, 43 percent of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral grammar, but only 13 percent report difficulty with gestures.

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

Finding 8: International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

Finding 9: Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

The evidence is clear about the practices that matter for language development, and most teachers report using them frequently.

Finding 10: International and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence is clear that the practices that best support the development of oral language skills are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversation to extend language |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication |

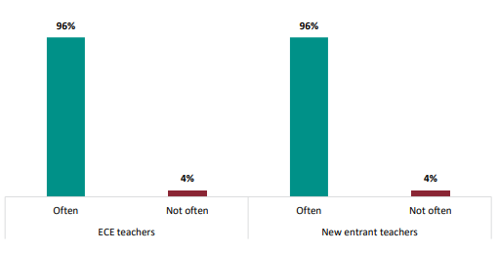

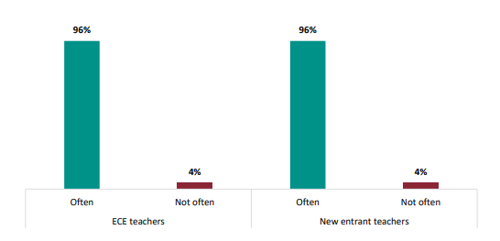

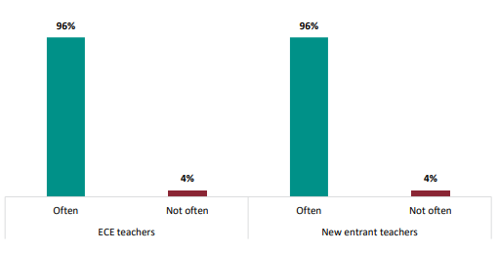

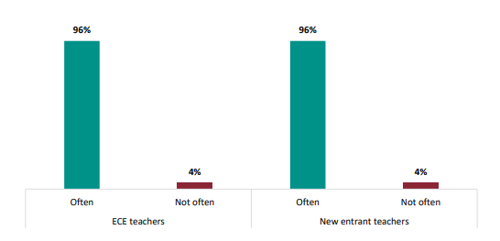

Finding 11: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed reported they use these evidence-based practices often. ECE teachers reported that they most often teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), use conversation to extend language (95 percent), and read interactively with children (95 percent). New entrant teachers we surveyed reported they most frequently read interactively with children (99 percent), teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), and model how words make sentences (95 percent).

Teachers’ practices to develop social communication are weaker.

Finding 12: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed both reported to us they develop social communication skills least frequently.

Professional knowledge is the strongest driver of teachers using evidence-based good practices. Qualified ECE teachers reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about oral language.

Finding 13: Qualified ECE teachers we surveyed reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about how oral language develops than non-qualified teachers. Most qualified ECE teachers (94 percent) reported being confident, but only two-thirds (64 percent) of non-qualified teachers reported being confident.

Finding 14: Qualified teachers reported more frequently using key practices, for example, using conversation to extend language (96 percent compared with 92 percent of non-qualified teachers).

Finding 15: ECE teachers who reported being extremely confident in their professional knowledge of how children’s language develops were up to seven times more likely to report using effective teaching practices regularly.

“We got the [provider] to come in and talk to us about the science, and the brain, and the neuroscience behind basically play-based learning.” (Teacher)

“You know that you are using this strategy that is researched and proven to work.” (Teacher)

Teachers and parents often do not know how well their children are developing and this matters as timely support can prevent problems later.

Finding 16: Not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to assess oral language progress. Of the new entrant teachers we surveyed, a quarter reported not being confident to assess and report on progress. The lack of clear development expectations and indicators of progress, and lack of alignment between Te Whāriki and the New Zealand Curriculum, makes this difficult. Half of parents (53 percent) do not get information from their service about their child’s oral language progress.

Finding 17: Being able to assess children’s oral language progress and identify potential difficulties is an important part of teaching young children. However, not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to identify difficulties in oral language (15 percent of ECE teachers and 24 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed report not being confident).

Finding 18: For children who are struggling, support from specialists, such as speech-language therapists, who can help with oral language development is key. But not all teachers are confident to work with these specialists, with 12 percent of ECE teachers and 17 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed reporting not being confident.

“Many are attending ECE, but not being referred early enough once the delay in oral language is noticed. Then when trying to get intervention, the wait times are too long and the support is inconsistent.” (New entrant teacher)

ERO has identified five areas for action to support children’s oral language development.

Area 1: Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities

1) Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities through removing barriers.

2) Raise the quality of ECE for children in low socio-economic communities – including through ERO reviews and Ministry of Education interventions.

Area 2: Put in place clear and consistent expectations and track children’s progress

3) Review how the New Zealand Curriculum at the start of school and

Te Whāriki work together to provide clear and consistent progress

indicators for oral language.

4) Make sure there are good tools that are used by ECE teachers to track progress and identify difficulties in children’s language development.

5) Assess children’s oral language at the start of school to help teachers to identify any tailored support or approaches they may need.

Area 3: Increase teachers’ use of effective practices

6) In initial teacher education for ECE and new entrant teachers, have a clear focus on the evidence-based practices that support oral language development.

7) Increase professional knowledge of oral language development, in

particular for non-qualified ECE teachers, through effective professional

learning and development.

Area 4: Support parents and whānau to develop language at home

8) Support ECE services to provide regular updates on children’s oral language development to parents and whānau.

9) Support ECE services in low socio-economic communities to provide

resources to parents and whānau to use with their children.

Area 5: Increase targeted support

10) Invest in targeted programmes and approaches that prevent and address delays in language development (e.g., Oral Language and Literacy Initiative and Better Start Literacy Approach).

Conclusion

Oral language is a critical building block for all children and essential to setting them up to succeed at school and beyond. Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind (including children in lower socio-economic communities), and Covid-19 has made this worse. Quality ECE can make a difference.

We have identified five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development. Together, these areas of action can help address the oral language challenges children face. We have developed a suite of oral language evaluation, practice, and support resources for key individuals in the education sector and parents and whānau to use to support children with their oral language development.

ERO’s suite of oral language evaluation, practice, and support resources

|

Title |

What’s it about? |

Who is it for? |

|

Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years (Evaluation report) |

The evaluation report shares what ERO found out about what is happening with oral language in ECE and new entrant classrooms.

|

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector. |

|

Good practice: Oral |

The good practice report sets out how services can support oral language

|

Teachers, leaders, |

|

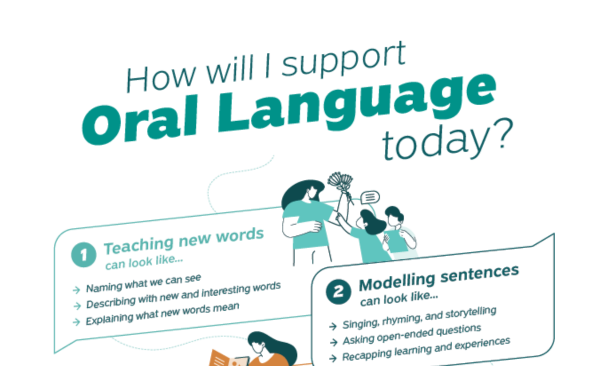

Poster for teachers: |

This poster sets out

|

Early childhood teachers |

|

Guide for ECE teachers: Oral language development in |

This guide for ECE

|

ECE teachers |

|

Guide for ECE leaders: Oral language |

This guide for ECE leaders explains how they can support oral language development.

|

ECE leaders |

|

Insights for new entrant teachers: Oral language development in the |

This brief guide for new

|

New entrant teachers |

|

Insights for parents |

This brief guide parents

|

Parents and whānau |

Language is the foundation for children’s learning and success. Children use oral language to become good thinkers and communicators, and to develop the literacy skills they need to achieve well in school and beyond. This report draws together a range of evidence to look at how well children are developing the oral language skills they need when they start school. We also look at how early childhood education (ECE) can help children to develop these important skills.

ERO found that while most children’s oral language is developing well, there is a significant group of children who struggle, and Covid-19 has made this worse. Quality ECE makes a difference, and the evidence shows there are key teaching practices that matter. We recommend five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development.

What is oral language?

Oral language is how we use spoken words to express ideas, knowledge, and feelings. Developing oral language involves developing the skills and knowledge that go into listening and speaking. These skills are important foundations for learning how to read and write. ERO looked at eight areas of language development:

|

Gestures |

Using and adding gestures as part of communication |

|

Words |

Learning, understanding, and using a range of words |

|

Sounds |

Adding, using, and understanding sounds |

|

Social communication |

Changing their language, using words to express needs |

|

Syntax |

Combining words to form sentences |

|

Stories |

Enjoy listening to, being read to, and telling stories |

|

Grammar |

Constructing nearly correct sentences and asking questions |

|

Rhyming |

Making rhymes |

What are the early years?

ERO looked at oral language development of children aged 0 to 7 years old in ECE and new entrant classes.

What did ERO look at?

ERO drew together a wide range of established international and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence. We also surveyed and spoke to parents and whānau, ECE and new entrant teachers, ECE service leaders, and a range of sector experts to understand how well children across Aotearoa New Zealand are developing oral language skills and how well supported they are. ERO visited a selection of ECE services and new entrant classrooms across Aotearoa New Zealand to better understand children’s progress and the teaching practices that support them.

Key findings

Oral language is critical for achieving the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Finding 1: Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and delays in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind and Covid-19 has made this worse.

Finding 2: A large Aotearoa New Zealand study found 80 percent of children at age 5 are doing well, but 20 percent are struggling with oral language. ECE and new entrant teachers also report that a group of children are struggling and half of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Finding 3: Covid-19 has had a significant impact. Nearly two-thirds of teachers (59 percent of ECE teachers and 65 percent of new entrant teachers) report that Covid-19 has impacted children’s language development. Teachers told us that social communication was particularly impacted by Covid-19, particularly language skills for social communication. International studies confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on language development.

"A lot of children are not able to communicate their needs. They are difficult to understand when they speak. They are not used to having conversations." (Teacher)

Children from low socio-economic communities and boys are struggling the most.

Finding 4: Evidence both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally is clear that children from lower socio-economic communities are more likely to struggle with oral language skills. We found that new entrant teachers we surveyed in schools in low socio-economic communities were nine times more likely to report children being below expected levels of oral language. Parents and whānau with lower qualifications were also more likely to report that their child has difficulty with oral language.

Finding 5: Both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally, boys have more difficulty developing oral language than girls. Parents and whānau we surveyed reported 70 percent of boys are not at the expected development level, compared with 56 percent of girls.

Difficulties with oral language emerge as children develop and oral language becomes more complex.

Finding 6: Teachers and parents and whānau report more concerns about children being behind as they become older and start school. For example, 56 percent of parents and whānau report their child has difficulty as a toddler (aged 18 months to 3 years old), compared to over two-thirds of parents and whānau (70 percent) reporting that their child has difficulty as a preschooler (aged 3 to 5).

Finding 7: Teachers and parents and whānau reported to us that children who are behind most often struggle with constructing sentences, telling stories, and using social communication to talk about their thoughts and feelings. For example, 43 percent of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral grammar, but only 13 percent report difficulty with gestures.

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

Finding 8: International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

Finding 9: Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

The evidence is clear about the practices that matter for language development, and most teachers report using them frequently.

Finding 10: International and Aotearoa New Zealand evidence is clear that the practices that best support the development of oral language skills are:

|

Practice area 1 |

Teaching new words and how to use them |

|

Practice area 2 |

Modelling how words make sentences |

|

Practice area 3 |

Reading interactively with children |

|

Practice area 4 |

Using conversation to extend language |

|

Practice area 5 |

Developing positive social communication |

Finding 11: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed reported they use these evidence-based practices often. ECE teachers reported that they most often teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), use conversation to extend language (95 percent), and read interactively with children (95 percent). New entrant teachers we surveyed reported they most frequently read interactively with children (99 percent), teach new words and how to use them (96 percent), and model how words make sentences (95 percent).

Teachers’ practices to develop social communication are weaker.

Finding 12: ECE and new entrant teachers we surveyed both reported to us they develop social communication skills least frequently.

Professional knowledge is the strongest driver of teachers using evidence-based good practices. Qualified ECE teachers reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about oral language.

Finding 13: Qualified ECE teachers we surveyed reported being almost twice as confident in their knowledge about how oral language develops than non-qualified teachers. Most qualified ECE teachers (94 percent) reported being confident, but only two-thirds (64 percent) of non-qualified teachers reported being confident.

Finding 14: Qualified teachers reported more frequently using key practices, for example, using conversation to extend language (96 percent compared with 92 percent of non-qualified teachers).

Finding 15: ECE teachers who reported being extremely confident in their professional knowledge of how children’s language develops were up to seven times more likely to report using effective teaching practices regularly.

“We got the [provider] to come in and talk to us about the science, and the brain, and the neuroscience behind basically play-based learning.” (Teacher)

“You know that you are using this strategy that is researched and proven to work.” (Teacher)

Teachers and parents often do not know how well their children are developing and this matters as timely support can prevent problems later.

Finding 16: Not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to assess oral language progress. Of the new entrant teachers we surveyed, a quarter reported not being confident to assess and report on progress. The lack of clear development expectations and indicators of progress, and lack of alignment between Te Whāriki and the New Zealand Curriculum, makes this difficult. Half of parents (53 percent) do not get information from their service about their child’s oral language progress.

Finding 17: Being able to assess children’s oral language progress and identify potential difficulties is an important part of teaching young children. However, not all ECE and new entrant teachers are confident to identify difficulties in oral language (15 percent of ECE teachers and 24 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed report not being confident).

Finding 18: For children who are struggling, support from specialists, such as speech-language therapists, who can help with oral language development is key. But not all teachers are confident to work with these specialists, with 12 percent of ECE teachers and 17 percent of new entrant teachers surveyed reporting not being confident.

“Many are attending ECE, but not being referred early enough once the delay in oral language is noticed. Then when trying to get intervention, the wait times are too long and the support is inconsistent.” (New entrant teacher)

ERO has identified five areas for action to support children’s oral language development.

Area 1: Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities

1) Increase participation in quality ECE for children from low socio-economic communities through removing barriers.

2) Raise the quality of ECE for children in low socio-economic communities – including through ERO reviews and Ministry of Education interventions.

Area 2: Put in place clear and consistent expectations and track children’s progress

3) Review how the New Zealand Curriculum at the start of school and

Te Whāriki work together to provide clear and consistent progress

indicators for oral language.

4) Make sure there are good tools that are used by ECE teachers to track progress and identify difficulties in children’s language development.

5) Assess children’s oral language at the start of school to help teachers to identify any tailored support or approaches they may need.

Area 3: Increase teachers’ use of effective practices

6) In initial teacher education for ECE and new entrant teachers, have a clear focus on the evidence-based practices that support oral language development.

7) Increase professional knowledge of oral language development, in

particular for non-qualified ECE teachers, through effective professional

learning and development.

Area 4: Support parents and whānau to develop language at home

8) Support ECE services to provide regular updates on children’s oral language development to parents and whānau.

9) Support ECE services in low socio-economic communities to provide

resources to parents and whānau to use with their children.

Area 5: Increase targeted support

10) Invest in targeted programmes and approaches that prevent and address delays in language development (e.g., Oral Language and Literacy Initiative and Better Start Literacy Approach).

Conclusion

Oral language is a critical building block for all children and essential to setting them up to succeed at school and beyond. Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind (including children in lower socio-economic communities), and Covid-19 has made this worse. Quality ECE can make a difference.

We have identified five key areas of action to support children’s oral language development. Together, these areas of action can help address the oral language challenges children face. We have developed a suite of oral language evaluation, practice, and support resources for key individuals in the education sector and parents and whānau to use to support children with their oral language development.

ERO’s suite of oral language evaluation, practice, and support resources

|

Title |

What’s it about? |

Who is it for? |

|

Let’s keep talking: Oral language development in the early years (Evaluation report) |

The evaluation report shares what ERO found out about what is happening with oral language in ECE and new entrant classrooms.

|

Teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, learning support staff, specialists, and the wider education sector. |

|

Good practice: Oral |

The good practice report sets out how services can support oral language

|

Teachers, leaders, |

|

Poster for teachers: |

This poster sets out

|

Early childhood teachers |

|

Guide for ECE teachers: Oral language development in |

This guide for ECE

|

ECE teachers |

|

Guide for ECE leaders: Oral language |

This guide for ECE leaders explains how they can support oral language development.

|

ECE leaders |

|

Insights for new entrant teachers: Oral language development in the |

This brief guide for new

|

New entrant teachers |

|

Insights for parents |

This brief guide parents

|

Parents and whānau |

About this report

Language is the foundation for children’s ongoing learning and success. Children use oral language to become good thinkers and communicators, and to develop the literacy skills they need to achieve well in school and in life. This report looks at how well children are developing oral language skills, and at the range of teaching practices that support oral language development.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early childhood education services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at the performance of the education system, the effectiveness of programmes and interventions, and good educational practice.

In this report, ERO looks at how well children’s oral language is developing in the early years, the teaching practices used by Early Childhood Education (ECE) teachers and new entrant teachers to develop children’s oral language, and the conditions which support good practices. We also outline what good practice strategies look like, based on research evidence, for supporting children’s oral language development.

This report describes what we found out about the current state of oral language in the early years in Aotearoa New Zealand. To do this, we looked at international and local evidence, and worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group that included academics, teachers, practitioners, and oral language experts.

As well as drawing together the established evidence, we learned through rich observations in early learning services and new entrant classrooms. Through surveys as well as in-depth interviews, we draw on the experiences of ECE leaders and teachers, new entrant teachers, primary school leaders, parents and whānau, and key experts. Together, these present a picture of how children’s oral language development is tracking, as well as the teaching that is happening to strengthen children’s oral language.

What we looked at

This evaluation looks at the current state of oral language in the early years and what can be done to improve children’s oral language. Across this work, we answer five key questions.

- What is the current level of oral language development? (for 0 to 7-year-olds)

- What impact has Covid-19 had?

- How can ECE support oral language development and what does good practice look like?

- How well are teachers in ECE and new entrant classes supporting oral language development?

- What could strengthen oral language development in ECE?

Good practice teaching strategies for promoting children’s oral language development, and the supports that underpin them, are unpacked in greater detail in our companion report: Good practice: Oral language development in the early years.

Our companion good practice resources for ECE teachers and leaders, parents and whānau, and new entrant teachers, can be found on our website: evidence.ero.govt.nz

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on children in ECE and in new entrant classes, their parents and whānau, and teachers and leaders in ECE services and new entrant classes across Aotearoa New Zealand.

This report does not look specifically at the oral language development needs of disabled learners.

Many children in Aotearoa New Zealand come from multilingual households and are learning two or more languages. We do not report specifically on children who are learning English as an additional language as a group in this report, but do discuss multilingual language learning.

English, te reo Māori, and more.

Our site visits and surveys draw from ‘English medium’ services and schools. (For evaluations that look at language learning in Māori-medium and Māori immersion early learning services, see our reports: ‘Āhuru mōwai’ (Te Kōhanga Reo) and ‘Tuia te here tangata: Making meaningful connections' (Puna Reo).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, all licensed ECE services are expected to provide opportunities for children to build their understanding of te reo Māori as well as English (and/or other languages relevant to the community), as part of the everyday experiences and learning that happen there. Ensuring children are able to access te reo Māori, and reflecting the cultures and languages of children and families at the service, is required and affirmed by our guiding curriculum and regulatory frameworks. When we talk about oral language in this report, this includes oral language in English, te reo Māori, and more.

Some of our survey and site visit data comes from Pacific bilingual services, which primarily use Pacific languages as well as some English and te reo Maori.

How we found out about the current state of oral language and teachers’ practice

This report draws together the wide range of international and New Zealand evidence about oral language development in the early years. In particular we draw on:

- international meta-analysis of good practice in supporting oral language and contextualising it to Aotearoa New Zealand

- Aotearoa New Zealand and international longitudinal studies (GUiNZ4, SEED5 and EPPSE6) and administrative data

- surveys of:

- 540 parents and whānau of children at early childhood education services and new entrant classes

- 308 ECE teachers

- 105 new entrant teachers

- observations of:

- 10 ECE services across Aotearoa New Zealand

- 10 new entrant classrooms in six schools

- in-depth interviews with:

- 15 parents and whānau

- 35 ECE teachers

- 10 new entrant teachers from six schools

- five speech-language therapists

- five key informants (e.g., Ministry of Education leads).

International and New Zealand evidence, alongside our surveys, rich observations and in-depth interviews presents a nuanced picture of the current level of oral language of children in New Zealand and how children can best be supported to develop their oral language.

How this fits with previous ERO reviews

In 2017, ERO asked early learning services and schools what they were doing in response to children’s oral language and development. We reported on the importance of supporting oral language learning and development from a very early age, with evidence showing these years are critical in terms of the rapid language development of children.

Appendix 1 sets out findings and recommendations from ERO’s 2017 report in more detail.

Report structure

This report is divided into six chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of oral language, the role of ECE in supporting language development, and which children attend ECE.

- Chapter 2 describes how well children are developing in oral language.

- Chapter 3 sets out good practice in oral language development. (More detail can be found in our companion good practice report.)

- Chapter 4 sets out how well teachers are supporting children’s language development using key teaching practices.

- Chapter 5 describes how well teachers are supported to develop children’s oral language.

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.

Language is the foundation for children’s ongoing learning and success. Children use oral language to become good thinkers and communicators, and to develop the literacy skills they need to achieve well in school and in life. This report looks at how well children are developing oral language skills, and at the range of teaching practices that support oral language development.

The Education Review Office (ERO) is responsible for reviewing and reporting on the performance of early childhood education services, kura, and schools. As part of this role, ERO looks at the performance of the education system, the effectiveness of programmes and interventions, and good educational practice.

In this report, ERO looks at how well children’s oral language is developing in the early years, the teaching practices used by Early Childhood Education (ECE) teachers and new entrant teachers to develop children’s oral language, and the conditions which support good practices. We also outline what good practice strategies look like, based on research evidence, for supporting children’s oral language development.

This report describes what we found out about the current state of oral language in the early years in Aotearoa New Zealand. To do this, we looked at international and local evidence, and worked closely with an Expert Advisory Group that included academics, teachers, practitioners, and oral language experts.

As well as drawing together the established evidence, we learned through rich observations in early learning services and new entrant classrooms. Through surveys as well as in-depth interviews, we draw on the experiences of ECE leaders and teachers, new entrant teachers, primary school leaders, parents and whānau, and key experts. Together, these present a picture of how children’s oral language development is tracking, as well as the teaching that is happening to strengthen children’s oral language.

What we looked at

This evaluation looks at the current state of oral language in the early years and what can be done to improve children’s oral language. Across this work, we answer five key questions.

- What is the current level of oral language development? (for 0 to 7-year-olds)

- What impact has Covid-19 had?

- How can ECE support oral language development and what does good practice look like?

- How well are teachers in ECE and new entrant classes supporting oral language development?

- What could strengthen oral language development in ECE?

Good practice teaching strategies for promoting children’s oral language development, and the supports that underpin them, are unpacked in greater detail in our companion report: Good practice: Oral language development in the early years.

Our companion good practice resources for ECE teachers and leaders, parents and whānau, and new entrant teachers, can be found on our website: evidence.ero.govt.nz

Where we looked

We focused our investigation on children in ECE and in new entrant classes, their parents and whānau, and teachers and leaders in ECE services and new entrant classes across Aotearoa New Zealand.

This report does not look specifically at the oral language development needs of disabled learners.

Many children in Aotearoa New Zealand come from multilingual households and are learning two or more languages. We do not report specifically on children who are learning English as an additional language as a group in this report, but do discuss multilingual language learning.

English, te reo Māori, and more.

Our site visits and surveys draw from ‘English medium’ services and schools. (For evaluations that look at language learning in Māori-medium and Māori immersion early learning services, see our reports: ‘Āhuru mōwai’ (Te Kōhanga Reo) and ‘Tuia te here tangata: Making meaningful connections' (Puna Reo).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, all licensed ECE services are expected to provide opportunities for children to build their understanding of te reo Māori as well as English (and/or other languages relevant to the community), as part of the everyday experiences and learning that happen there. Ensuring children are able to access te reo Māori, and reflecting the cultures and languages of children and families at the service, is required and affirmed by our guiding curriculum and regulatory frameworks. When we talk about oral language in this report, this includes oral language in English, te reo Māori, and more.

Some of our survey and site visit data comes from Pacific bilingual services, which primarily use Pacific languages as well as some English and te reo Maori.

How we found out about the current state of oral language and teachers’ practice

This report draws together the wide range of international and New Zealand evidence about oral language development in the early years. In particular we draw on:

- international meta-analysis of good practice in supporting oral language and contextualising it to Aotearoa New Zealand

- Aotearoa New Zealand and international longitudinal studies (GUiNZ4, SEED5 and EPPSE6) and administrative data

- surveys of:

- 540 parents and whānau of children at early childhood education services and new entrant classes

- 308 ECE teachers

- 105 new entrant teachers

- observations of:

- 10 ECE services across Aotearoa New Zealand

- 10 new entrant classrooms in six schools

- in-depth interviews with:

- 15 parents and whānau

- 35 ECE teachers

- 10 new entrant teachers from six schools

- five speech-language therapists

- five key informants (e.g., Ministry of Education leads).

International and New Zealand evidence, alongside our surveys, rich observations and in-depth interviews presents a nuanced picture of the current level of oral language of children in New Zealand and how children can best be supported to develop their oral language.

How this fits with previous ERO reviews

In 2017, ERO asked early learning services and schools what they were doing in response to children’s oral language and development. We reported on the importance of supporting oral language learning and development from a very early age, with evidence showing these years are critical in terms of the rapid language development of children.

Appendix 1 sets out findings and recommendations from ERO’s 2017 report in more detail.

Report structure

This report is divided into six chapters.

- Chapter 1 sets out the context of oral language, the role of ECE in supporting language development, and which children attend ECE.

- Chapter 2 describes how well children are developing in oral language.

- Chapter 3 sets out good practice in oral language development. (More detail can be found in our companion good practice report.)

- Chapter 4 sets out how well teachers are supporting children’s language development using key teaching practices.

- Chapter 5 describes how well teachers are supported to develop children’s oral language.

We appreciate the work of all those who supported this research, particularly the teachers, leaders, parents and whānau, and experts who shared with us. Their experiences and insights are at the heart of what we have learnt.

Chapter 1: Context

Oral language is the most common way we share our ideas, experiences, and feelings with others and how we understand people around us. Oral language is also foundational to reading and writing. Children need to learn to speak and listen before they can learn to read. Quality early childhood education can help build and strengthen children’s oral language so that they are set up for success to communicate well with others, share their ideas and experiences, read and write when they start school, and more.

This section sets out what oral language is, why it is important, and the role of early childhood education services in supporting oral language development.

This chapter outlines:

- what oral language is, including the aspects of oral language

- why oral language is important

- oral language indicators of progress

- how ECE can help children develop oral language

- which children are participating in ECE.

What we found: An overview

Oral language is critical for the achievement of the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and difficulties in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

1) What is oral language?

Language is key to human connection and communication. It is essential for people to navigate through the world effectively. People communicate in a variety of ways, ranging from gestures to written and oral language. Oral language is the most common form of communication and includes:

→ listening (receptive language) skills: the ability to hear, process, and understand information

→ speaking (expressive language) skills: the ability to respond and make meaning from sounds, words, gestures or signing.

Through listening and speaking, children learn to communicate their views, understand others, and make and share their discoveries. In Te Whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s ECE curriculum, oral language includes any method of communication the child uses in their first language.

We recognise Te Whāriki includes non-verbal methods of communication (e.g., NZSL, and use of assistive technologies). However, in this report, we refer to oral language as spoken communication in a child’s first language (the language they speak at home), because the evidence base available is robust for spoken language, while non-verbal language encompasses vastly different skills and strategies.

2) Why is oral language important?

Children’s early oral language learning is critical for educational achievement later. It predicts academic success and retention rates at secondary school. Early measures of language, such as vocabulary at 2 years of age, predict academic achievement at 12 years of age and in secondary school.

Children need oral language to become proficient thinkers, communicators, and learners. Oral language is the foundation of literacy, helps children fully participate at school, is critical for children to recognise and express their own feelings and needs, and to recognise and respond to the feelings and needs of others.

Oral language is the foundation of literacy.

Before children can read and write, they need to be able to understand language. Children’s early reading, writing, and comprehension skills all build on their oral language.16 Oral language development links to better outcomes in reading comprehension, articulation of thoughts and ideas, vocabulary, and grammar.

Oral language enables communication in the learning environment.

Oral language is used for sharing thoughts and transmitting knowledge. Oral language development includes using language for social communication and discussions with peers at ECE and school. It is needed for conversational skills in small groups, including being able to initiate, join, and end conversations. It also helps children learn more effectively, apply their learning through problem solving,

and address challenges.

Oral language skills help children communicate their needs and wants.

Poor social communication skills in childhood relate to behavioural problems when children have difficulty communicating what they need and want, and get frustrated, which is estimated to affect up to 10 percent of children in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Raising literacy levels

With many students starting below expected levels at secondary school, the New Zealand Government has set expectations for achieving improved literacy levels for Year 8 students. The Government has set a target that 80 percent of Year 8 students will be at or above the expected curriculum level for their age in reading and writing by December 2030.

To achieve this, children need the foundations of reading comprehension. Longitudinal studies in the UK and Aotearoa New Zealand link oral language in the early years and achievement in reading comprehension and literacy assessments in primary and secondary school.

3) What are the indicators of progress for oral language?

In Aotearoa New Zealand, there are a range of sources for oral language progress markers or indicators. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health have both developed guidance and expectations for typical language development for children in their first five years. The Ministry of Education’s ‘Stepping stones’ for oral language development in the early years are set out in Table 1.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, early childhood education and school have separate curriculum documents. The ECE curriculum, Te Whāriki, provides an indication of some of the growing interests and capabilities seen in infants, toddlers, and young children. Oral language learning is also a part of the school curriculum, which includes guidance for oral language for 5 to 8-year-olds. The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) English learning area sets out achievement objectives on:

- making meaning of ideas or information that they receive, including listening

- creating meaning for themselves or others, including speaking.

Multilingual children

In Aotearoa New Zealand, 18 percent of children under the age of 14 years speak more than one language. Multilingual children can learn multiple languages at home, or can learn to speak one language at home and another in their learning environment.

Multilingual children who are capable in more than one language can have better creative thinking and multi-tasking skills, but children acquiring two or more languages at the same time do develop language at a different pace. It’s useful for teachers to be aware that it’s normal for multilingual children to take longer than children learning one language to:

→ have the same number of words in each language

→ combine words

→ build sentences

→ speak clearly.

Table 1: Stepping stones for language development

|

Stepping stones |

NZ Curriculum |

||

|

Infants (0-18 months) |

Toddlers (1-3 years) |

Pre-schoolers (2.5 – 5 years) |

New Entrants |

|

|

|

|

4) What is the role of ECE in supporting language development?

Quality early childhood education has a central role in supporting oral language development in the early years. In Aotearoa New Zealand, high quality ECE reflects ERO’s Indicators of Quality. ERO sets out domains, process indicators, and examples of effective practice that include professional learning, leadership, and curriculum expectations that contribute to positive learning outcomes for children. These include specific indicators and examples around:

- effective assessment, planning and evaluation of teaching and its impact on children’s learning and development

- the expectation that the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki are prioritised, and should provide the basis for assessment for learning

- thoughtfully and intentionally giving priority to oral language, recognising that it plays a crucial role in learning.

How does oral language fit in to Te Whāriki, the ECE curriculum?

Te Whāriki includes specific goals and outcomes related to oral language – such as developing non-verbal communication skills for a range of purposes (goal), and understanding oral language and using it for a range of purposes (learning outcome). The Mana Reo | Communication strand focuses on children’s communication skills, both verbal and non-verbal. As of May 2024, the principles, strands, goals, and learning outcomes of Te Whāriki will be gazetted - which means that all licensed early childhood services will be required to implement them.

Quality ECE supports language development.

Oral language and communication focused teaching in ECE services can help children make seven months’ additional progress on their language in a year.

Quality ECE reduces disparities in oral language for children when they start school.

Attending quality early childhood education services not only improves children’s language outcomes, but also reduces the disparity in the level of oral language at school entry.

Children from low socio-economic communities benefit most from quality ECE that focuses on language and communication development. Quality early childhood education services and skilled ECE teachers can provide rich, immersive language experiences for children, which have particular value if children are missing these opportunities at home.

The duration of enrolment and hours of attendance also make a significant difference to the long-term outcomes for children from low socio-economic communities. International studies show that regularly attending a quality early childhood education service reduces the effects of multiple disadvantages on later achievement and progress in primary school, with these children achieving better outcomes in reading, writing, and science at 7 years of age.

Quality ECE enables children who need additional support to be identified and supported earlier.

ECE teachers can notice language difficulties that may not be apparent to parents. Support from ECE services and speech-language therapists are effective in helping children get back on track.

5) Which children are participating in ECE?

In Aotearoa New Zealand it is not compulsory for children to attend early learning services, but most do.

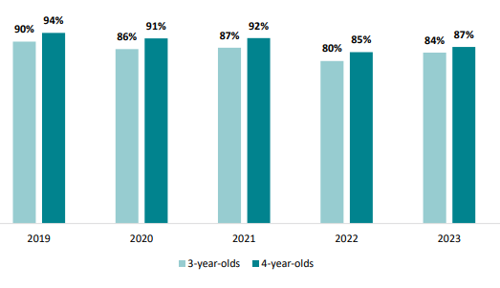

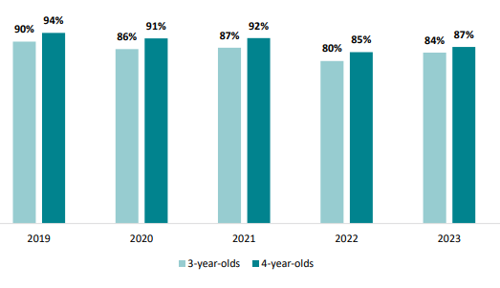

Nearly nine in 10 3- to 4-year-olds attend ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds attending ECE increased between 2022 and 2023, but it is still lower than before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds attending licensed ECE services, 2019-2023

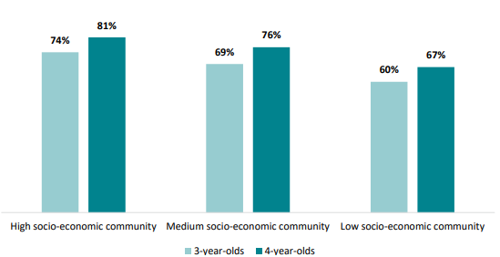

Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours.

International evidence shows that children from lower socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours. We also find this in Aotearoa New Zealand

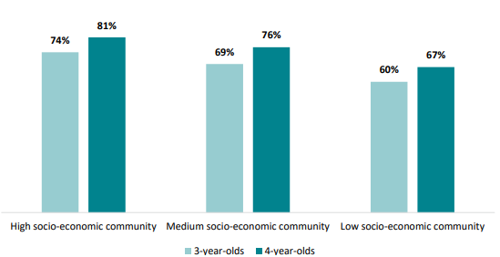

Of the 3-year-olds who attend ECE, less than two-thirds (60 percent) of children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for more than 10 hours per week, compared with three-quarters (74 percent) of children from high socio-economic communities.

Of the 4-year-olds who attend ECE, only two-thirds (67 percent) from low socio-economic communities attend more than 10 hours per week, compared with four in five (81 percent) from high socio-economic communities.

Figure 2: Proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds who attended ECE more than 10 hours per week, by socio-economic community, 2023

Conclusion

Good oral language skills support children’s later literacy and academic

achievement. Quality ECE can play a key role in supporting children’s oral language and literacy development. But concerningly, fewer children are attending ECE than before the Covid-19 pandemic, and children from lower socio-economic communities attend less. This is worrying, as the evidence is clear that quality ECE is especially effective in reducing inequity at school entry.

In the next chapter of the report we look at children’s oral language development, the impact of Covid-19, and the practices teachers in ECE services and new entrant classes are using to build children’s oral language.

Oral language is the most common way we share our ideas, experiences, and feelings with others and how we understand people around us. Oral language is also foundational to reading and writing. Children need to learn to speak and listen before they can learn to read. Quality early childhood education can help build and strengthen children’s oral language so that they are set up for success to communicate well with others, share their ideas and experiences, read and write when they start school, and more.

This section sets out what oral language is, why it is important, and the role of early childhood education services in supporting oral language development.

This chapter outlines:

- what oral language is, including the aspects of oral language

- why oral language is important

- oral language indicators of progress

- how ECE can help children develop oral language

- which children are participating in ECE.

What we found: An overview

Oral language is critical for the achievement of the Government’s literacy ambitions.

Oral language is critical for later literacy and education outcomes. It also plays a key role in developing key social-emotional skills that support behaviour. Children’s vocabulary at age 2 is strongly linked to their literacy and numeracy achievement at age 12, and difficulties in oral language in the early years are reflected in poor reading comprehension at school.

Quality ECE makes a difference, particularly to children in low socio-economic communities, but they attend ECE less often.

International studies find that quality ECE supports language development and can accelerate literacy by up to a year (particularly for children in low socio-economic communities), and that quality ECE leads to better academic achievement at age 16 for children from low socio-economic communities.

Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours than children in high socio-economic areas, which can be due to a range of factors.

1) What is oral language?

Language is key to human connection and communication. It is essential for people to navigate through the world effectively. People communicate in a variety of ways, ranging from gestures to written and oral language. Oral language is the most common form of communication and includes:

→ listening (receptive language) skills: the ability to hear, process, and understand information

→ speaking (expressive language) skills: the ability to respond and make meaning from sounds, words, gestures or signing.

Through listening and speaking, children learn to communicate their views, understand others, and make and share their discoveries. In Te Whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s ECE curriculum, oral language includes any method of communication the child uses in their first language.

We recognise Te Whāriki includes non-verbal methods of communication (e.g., NZSL, and use of assistive technologies). However, in this report, we refer to oral language as spoken communication in a child’s first language (the language they speak at home), because the evidence base available is robust for spoken language, while non-verbal language encompasses vastly different skills and strategies.

2) Why is oral language important?

Children’s early oral language learning is critical for educational achievement later. It predicts academic success and retention rates at secondary school. Early measures of language, such as vocabulary at 2 years of age, predict academic achievement at 12 years of age and in secondary school.

Children need oral language to become proficient thinkers, communicators, and learners. Oral language is the foundation of literacy, helps children fully participate at school, is critical for children to recognise and express their own feelings and needs, and to recognise and respond to the feelings and needs of others.

Oral language is the foundation of literacy.

Before children can read and write, they need to be able to understand language. Children’s early reading, writing, and comprehension skills all build on their oral language.16 Oral language development links to better outcomes in reading comprehension, articulation of thoughts and ideas, vocabulary, and grammar.

Oral language enables communication in the learning environment.

Oral language is used for sharing thoughts and transmitting knowledge. Oral language development includes using language for social communication and discussions with peers at ECE and school. It is needed for conversational skills in small groups, including being able to initiate, join, and end conversations. It also helps children learn more effectively, apply their learning through problem solving,

and address challenges.

Oral language skills help children communicate their needs and wants.

Poor social communication skills in childhood relate to behavioural problems when children have difficulty communicating what they need and want, and get frustrated, which is estimated to affect up to 10 percent of children in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Raising literacy levels

With many students starting below expected levels at secondary school, the New Zealand Government has set expectations for achieving improved literacy levels for Year 8 students. The Government has set a target that 80 percent of Year 8 students will be at or above the expected curriculum level for their age in reading and writing by December 2030.

To achieve this, children need the foundations of reading comprehension. Longitudinal studies in the UK and Aotearoa New Zealand link oral language in the early years and achievement in reading comprehension and literacy assessments in primary and secondary school.

3) What are the indicators of progress for oral language?

In Aotearoa New Zealand, there are a range of sources for oral language progress markers or indicators. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health have both developed guidance and expectations for typical language development for children in their first five years. The Ministry of Education’s ‘Stepping stones’ for oral language development in the early years are set out in Table 1.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, early childhood education and school have separate curriculum documents. The ECE curriculum, Te Whāriki, provides an indication of some of the growing interests and capabilities seen in infants, toddlers, and young children. Oral language learning is also a part of the school curriculum, which includes guidance for oral language for 5 to 8-year-olds. The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) English learning area sets out achievement objectives on:

- making meaning of ideas or information that they receive, including listening

- creating meaning for themselves or others, including speaking.

Multilingual children

In Aotearoa New Zealand, 18 percent of children under the age of 14 years speak more than one language. Multilingual children can learn multiple languages at home, or can learn to speak one language at home and another in their learning environment.

Multilingual children who are capable in more than one language can have better creative thinking and multi-tasking skills, but children acquiring two or more languages at the same time do develop language at a different pace. It’s useful for teachers to be aware that it’s normal for multilingual children to take longer than children learning one language to:

→ have the same number of words in each language

→ combine words

→ build sentences

→ speak clearly.

Table 1: Stepping stones for language development

|

Stepping stones |

NZ Curriculum |

||

|

Infants (0-18 months) |

Toddlers (1-3 years) |

Pre-schoolers (2.5 – 5 years) |

New Entrants |

|

|

|

|

4) What is the role of ECE in supporting language development?

Quality early childhood education has a central role in supporting oral language development in the early years. In Aotearoa New Zealand, high quality ECE reflects ERO’s Indicators of Quality. ERO sets out domains, process indicators, and examples of effective practice that include professional learning, leadership, and curriculum expectations that contribute to positive learning outcomes for children. These include specific indicators and examples around:

- effective assessment, planning and evaluation of teaching and its impact on children’s learning and development

- the expectation that the learning outcomes in Te Whāriki are prioritised, and should provide the basis for assessment for learning

- thoughtfully and intentionally giving priority to oral language, recognising that it plays a crucial role in learning.

How does oral language fit in to Te Whāriki, the ECE curriculum?

Te Whāriki includes specific goals and outcomes related to oral language – such as developing non-verbal communication skills for a range of purposes (goal), and understanding oral language and using it for a range of purposes (learning outcome). The Mana Reo | Communication strand focuses on children’s communication skills, both verbal and non-verbal. As of May 2024, the principles, strands, goals, and learning outcomes of Te Whāriki will be gazetted - which means that all licensed early childhood services will be required to implement them.

Quality ECE supports language development.

Oral language and communication focused teaching in ECE services can help children make seven months’ additional progress on their language in a year.

Quality ECE reduces disparities in oral language for children when they start school.

Attending quality early childhood education services not only improves children’s language outcomes, but also reduces the disparity in the level of oral language at school entry.

Children from low socio-economic communities benefit most from quality ECE that focuses on language and communication development. Quality early childhood education services and skilled ECE teachers can provide rich, immersive language experiences for children, which have particular value if children are missing these opportunities at home.

The duration of enrolment and hours of attendance also make a significant difference to the long-term outcomes for children from low socio-economic communities. International studies show that regularly attending a quality early childhood education service reduces the effects of multiple disadvantages on later achievement and progress in primary school, with these children achieving better outcomes in reading, writing, and science at 7 years of age.

Quality ECE enables children who need additional support to be identified and supported earlier.

ECE teachers can notice language difficulties that may not be apparent to parents. Support from ECE services and speech-language therapists are effective in helping children get back on track.

5) Which children are participating in ECE?

In Aotearoa New Zealand it is not compulsory for children to attend early learning services, but most do.

Nearly nine in 10 3- to 4-year-olds attend ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds attending ECE increased between 2022 and 2023, but it is still lower than before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds attending licensed ECE services, 2019-2023

Children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours.

International evidence shows that children from lower socio-economic communities attend ECE for fewer hours. We also find this in Aotearoa New Zealand

Of the 3-year-olds who attend ECE, less than two-thirds (60 percent) of children from low socio-economic communities attend ECE for more than 10 hours per week, compared with three-quarters (74 percent) of children from high socio-economic communities.

Of the 4-year-olds who attend ECE, only two-thirds (67 percent) from low socio-economic communities attend more than 10 hours per week, compared with four in five (81 percent) from high socio-economic communities.

Figure 2: Proportion of 3- and 4-year-olds who attended ECE more than 10 hours per week, by socio-economic community, 2023

Conclusion

Good oral language skills support children’s later literacy and academic

achievement. Quality ECE can play a key role in supporting children’s oral language and literacy development. But concerningly, fewer children are attending ECE than before the Covid-19 pandemic, and children from lower socio-economic communities attend less. This is worrying, as the evidence is clear that quality ECE is especially effective in reducing inequity at school entry.

In the next chapter of the report we look at children’s oral language development, the impact of Covid-19, and the practices teachers in ECE services and new entrant classes are using to build children’s oral language.

Chapter 2: How well are children developing in oral language?

Children’s oral language development is critical to later literacy but some children are having difficulties, and this impacts on their ongoing learning. Boys, and children from low socio-economic communities, struggle the most.

In this chapter, we set out how different aspects of children’s language are developing, where there are key differences are in children’s capabilities, and discuss the impact Covid-19 has had on children’s oral language.

What we did

There are many aspects to oral language development, and factors that contribute to successful development. To understand how well children are developing oral language in the early years, we looked at:

- international evidence

- national longitudinal studies

- our surveys of ECE teachers, new entrant teachers, and parents and whānau

- our interviews with ECE leaders and teachers, primary school leaders and new entrant teachers, key experts, and parents and whānau.

This section sets out what we found about:

- language development in the early years

- where children are at when they start school

- impacts of Covid-19

- which aspects of oral language children can struggle with most

- differences in progress for boys, multilingual children, and children in low socio-economic communities.

What we found: an overview

Most children’s oral language is developing well, but there is a significant group of children who are behind and Covid-19 has made this worse.

A large Aotearoa New Zealand study found 80 percent of children at age 5 are developing well, but 20 percent are struggling with oral language. ECE and new entrant teachers also report that a group of children are struggling and more than half of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Covid-19 has had a significant impact. Nearly two-thirds of teachers (59 percent of ECE teachers and 65 percent of new entrant teachers) report that Covid-19 has impacted children’s language development, particularly language skills for social communication. International studies confirm the significant impact of Covid-19 on language development.

Children from low socio-economic communities and boys are struggling the most.

Evidence both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally is clear that children from lower socio-economic communities are more likely to struggle with oral language skills. We found that new entrant teachers we surveyed in schools in low socio-economic communities were nine times more likely to report children being below expected levels of oral language. Parents and whānau with lower qualifications were also more likely to report that their child has difficulty with oral

language.

Both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally, boys have more difficulty developing oral language than girls. Parents and whānau we surveyed reported 70 percent of boys are not at the expected development level, compared with 56 percent of girls.

Difficulties with oral language emerge as children develop and oral language becomes more complex.

Teachers and parents and whānau report more concerns about students being behind as they become older and start school. For example, 56 percent of parents and whānau report their child has difficulty as a toddler (aged 18 months to 3 years old), compared to over two-thirds of parents and whānau (70 percent) reporting that their child has difficulty as a preschooler (aged 3 to 5).

Parents and whānau and teachers reported to us that children who are behind most often struggle with constructing sentences, telling stories, and using social communication to talk about their thoughts and feelings. For example, 43 percent of parents and whānau report their child has some difficulty with oral grammar, but only 13 percent report difficulty with gestures.

1) How well is oral language developing in the early years?

There is limited curriculum guidance and no national assessments.

Te Whāriki, the curriculum for early childhood education, includes goals and outcomes for oral language – such as ‘developing non-verbal communication skills for a range of purposes’ and ‘understanding oral language and using it for a range of purposes.’

The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) includes key competencies for students such as use of language. These are not closely related to Te Whāriki outcomes for children in ECE.

There is no national measure or system-level national data for how well children under 5 are developing oral language. While ‘B4 School Check’ assessments help identify hearing problems or speech difficulty for 4-year-olds, they don’t measure broader oral language development.

We have to rely on studies, such as the Growing Up in New Zealand study (GUiNZ) and what parents and whānau and ECE teachers see, to get a broader understanding of how well children’s oral language is developing in ECE and into junior primary school.

Most children develop oral language well, but around one in five children in Aotearoa New Zealand have poor oral language skills.

The GUiNZ study investigated over 5,000 4.5 - 5-year-olds’ oral language in 2019, using two verbal tasks. According to GUiNZ, one in five children had lower language ability in the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test which looks at children’s understanding of words, and a lower ability in the DIBELS Letter Naming Fluency task which looks at children’s ability to say the ‘names’ of letters.

According to GUiNZ, there is a high degree of variability in oral language in children. This variability continues in the first two years of primary school and can reflect that children’s development is not the same for all children and it does not always progress linearly.

ECE teachers report that most children’s oral language development is on track, but there is a significant group of children who are behind.

Most ECE teachers (89 percent) report three-quarters of the children they work with are at the expected level of oral language development. But 12 percent report that a quarter of the children they work with are behind.

Parents and whānau are also concerned.

More than half of parents and whānau (60 percent) with children under five report that their child has some difficulty with oral language in the early years.

Figure 3: Parents and whānau reporting of whether their child has difficulty with oral language

Teachers, parents and whānau become more concerned about language development as children get older.

In our surveys, we asked parents and whānau about whether their child has difficulty with oral language skills that are generally expected at their age. For example, ‘say simple sentences with two or more words in them’ for toddlers, and ‘tell longer stories’ for preschoolers.