Related insights

Explore related documents that might be interested in.

Read Online

Introduction

ERO found that Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) is critical to the learning, development, and wellbeing of New Zealand’s young people. We continue to have a range of worrying health and safety issues that directly relate to relationships and sexuality, including family and sexual violence, bullying, and racism. At a time where young people are increasingly exposed to harmful online content, including pornography and misinformation through social media, and hate speech, we heard that RSE plays an increasingly important role.

ERO’s evaluation found that while there is widespread support from students and parents for RSE being taught in schools, there is inconsistency in the RSE teaching and learning that students experience throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. What students are taught, if they are taught it, and when they are taught it can depend on where they go to school.

What is RSE?

Relationships and sexuality education (RSE) can include topics on bodies, reproduction, sexualities, bullying and online safety. RSE falls under the ‘Health and Physical Education’ learning area of the New Zealand Curriculum, which is compulsory in Years 1-10 (approx. ages 5-14). This requirement is similar to other countries, except New Zealand is less prescriptive about content, has a stronger requirement for consultation, and offers less guidance and support for teachers.

Schools design their own RSE programmes based on the New Zealand Curriculum and the optional RSE guidelines provided by the Ministry of Education. There are no set topics they must cover or amount of time students must study RSE. School boards are required to consult with their communities at least every two years on their RSE programme.

Why does RSE matter?

Most developed countries teach some form of RSE to support children’s and young people’s development, health, and safety. RSE focuses on a range key issues including preventing bullying, promoting healthy relationships and sexual health, and promoting inclusion and reducing discrimination - in the classroom and more widely in society. RSE also plays a key role in helping students to navigate a changing world, where online safety risks, misinformation and harmful attitudes are increasingly prevalent.

ERO found that Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) is critical to the learning, development, and wellbeing of New Zealand’s young people. We continue to have a range of worrying health and safety issues that directly relate to relationships and sexuality, including family and sexual violence, bullying, and racism. At a time where young people are increasingly exposed to harmful online content, including pornography and misinformation through social media, and hate speech, we heard that RSE plays an increasingly important role.

ERO’s evaluation found that while there is widespread support from students and parents for RSE being taught in schools, there is inconsistency in the RSE teaching and learning that students experience throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. What students are taught, if they are taught it, and when they are taught it can depend on where they go to school.

What is RSE?

Relationships and sexuality education (RSE) can include topics on bodies, reproduction, sexualities, bullying and online safety. RSE falls under the ‘Health and Physical Education’ learning area of the New Zealand Curriculum, which is compulsory in Years 1-10 (approx. ages 5-14). This requirement is similar to other countries, except New Zealand is less prescriptive about content, has a stronger requirement for consultation, and offers less guidance and support for teachers.

Schools design their own RSE programmes based on the New Zealand Curriculum and the optional RSE guidelines provided by the Ministry of Education. There are no set topics they must cover or amount of time students must study RSE. School boards are required to consult with their communities at least every two years on their RSE programme.

Why does RSE matter?

Most developed countries teach some form of RSE to support children’s and young people’s development, health, and safety. RSE focuses on a range key issues including preventing bullying, promoting healthy relationships and sexual health, and promoting inclusion and reducing discrimination - in the classroom and more widely in society. RSE also plays a key role in helping students to navigate a changing world, where online safety risks, misinformation and harmful attitudes are increasingly prevalent.

Key findings

Our evaluation led to 21 key findings in five areas:

Area 1: Is teaching RSE in schools supported?

We looked at whether students and parents and whānau support RSE being taught in schools.

Finding 1: There is wide support from students and parents and whānau for RSE being taught in schools.

- Over nine in 10 (91 percent) students support RSE being taught in schools. Girls are more likely to support it being taught, with 95 percent of girls supporting it and 88 percent of boys supporting it.

- Most parents and whānau (87 percent) support RSE being taught in schools.

- Parents and whānau who know what is being taught are happier with RSE.

- Some students d ecide to miss school to avoid RSE (7 percent), but others go to school because they want to learn RSE (9 percent).

Finding 2: Pacific parents, parents of primary aged students, and parents of faith are less supportive.

- Nearly three in 10 (29 percent) Pacific parents and whānau do not support RSE being taught in schools, due to cultural beliefs and reasons to do with their faith. Seventy-one percent do support it.

- Primary school parents and whānau are slightly less supportive (82 percent) than intermediate (89 percent) and secondary school (89 percent) parents and whānau, due to concerns about RSE content being appropriate for their children’s age.

- Parents and whānau who practice a faith are over two times more likely to not support RSE being taught. Over one in five parents who practice a faith (22 percent) do not support RSE being taught, compared to 9 percent of parents who do not practice a faith.

- Six percent of parents and whānau withdraw their child from RSE.

Figure 1: Parents and whānau views on whether RSE should be taught in schools

Area 2: What is being taught in RSE?

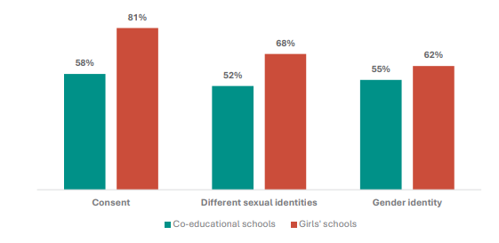

Finding 3: What students learn about depends on where they go to school.

- There is a lot of flexibility for schools around exactly which RSE content is taught, and how it is taught. Schools can develop their own programmes, rely on external providers, or both. No RSE content is compulsory, which means what students learn depends entirely on their school.

- RSE teaching across the country includes coverage of a wide range of topics, which relate broadly to personal safety, managing feelings, bodies, health, diverse identities, wellbeing, and relationships with other people.

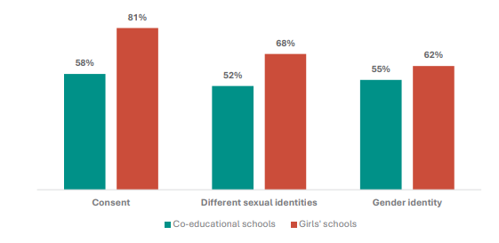

- Students in girls’ schools are more likely to learn about consent, different sexual identities, and gender identity than students at co-ed schools.

Finding 4: What students are taught changes as they grow up.

- In Years 0-4 (ages 5-8), almost all students learn about feelings and emotions, friendships and bullying, and personal safety. As they progress through years 5-8 (ages 8-12), they begin to learn about getting help with their health and changes to their body.

- At Years 9-10 (ages 12-14), around eight in 10 students learn about consent, romantic relationships, sexual identities, human reproduction, and gender identity.

- Students do not have to learn RSE in Years 11-13 (ages 14-18), but many do.

Finding 5: Sensitive topics are taught later. Different sexual identities, gender identity, and human reproduction are mostly taught in secondary school.

- Less than one in five teachers of students aged 8-10 report teaching sexual identities, gender identity, and human reproduction, compared to three-quarters of teachers of students aged 12-14.

Figure 3: Teachers report human reproduction, gender identity, and different sexual identities are taught at each level

Finding 6: What is taught in RSE is changing over time, as society changes.

- Only around one third of recent school leavers report they learnt about gender identity, gender stereotypes, and celebrating differences, compared to over two-thirds of current Year 11-13 students who report they learn about these topics.

Area 3: Does RSE meet students’ needs?

We looked at how well RSE is meeting the needs of students, and how this differs across different groups.

Finding 7: Most students agree that they are taught the right amount of most RSE topics and at the right age, though some topics aren’t being delivered at the right time to meet students’ needs.

- Across most topics, seven in 10 students say they are being taught the right amount and around half (41-55 percent) agree that they are learning it at the right time.

- Seven in 10 students want to learn about personal safety (including online safety) and friendships and bullying earlier.

- Students think the middle school years are too early for human reproduction learning. Six in 10 of Years 5-6 (60 percent) and half of Years 7-8 students (51 percent) want to learn about human reproduction later.

Figure 4: Students report when they would like to learn about friendships and bullying, and personal safety, including online safety

Finding 8: Boys are more likely to want to learn all topics later than girls, reflecting that boys may go through puberty later.

- Boys are more likely to want to learn all topics later than girls. The most common topics they want to learn about later are human reproduction (35 percent), different sexual identities (22 percent), and romantic relationships including intimate relationships (22 percent).

- Girls often want to learn more and earlier on key topics. Over a quarter of girls want to learn more about managing feelings and emotions (25 percent) and gender stereotypes (31 percent). Over three-quarters of girls want to learn about friendship and bullying (82 percent) and personal safety including online safety (75 percent) earlier.

Finding 9: Students’ views are split about when and how much they learn about human reproduction, different sexual identities, gender identity, and romantic relationships.

- Three in 10 students want to learn about human reproduction earlier (28 percent), and three in 10 want to learn it later (28 percent).

- A third of students want to learn about different sexual identities (33 percent), gender identity (36 percent), and romantic relationships (31 percent) earlier, and nearly one in five want to learn about these subjects later (16-18 percent).

Figure 5: Students report how much they learn about different sexual identities and gender identity

Finding 10: Students’ faith and sexuality impacts how well RSE meets their needs.

- Students of faith are more likely to want to learn less about gender identity and different sexual identities than students who do not practice a faith.

- Secondary school students from rainbow communities want to learn about all RSE topics earlier than other students.

Finding 11: Recent school leavers report that there were significant gaps in their RSE learning.

- Over three-quarters of the students didn’t learn and would have liked to learn about consent (82 percent), managing feelings and emotions (78 percent), personal safety, including online safety (78 percent), and changes to their body (75 percent). This reflects that what they learn depends on schools individual programmes.

Area 4: Does RSE meet the expectations of parents and whānau?

We looked at how well RSE is meeting the needs of parents and whānau, and how this differs across different groups.

Finding 12: A third of parents and whānau want to change what or how RSE is taught, and over one in 10 do not want it taught in schools.

- Thirty-four percent of parents and whānau think that RSE should be taught, but what or how it is taught should change. The proportion is higher for primary school parents and whānau (38 percent) than secondary (32 percent) because they are concerned about RSE content not being age appropriate.

- Fifty-three percent of parents and whānau think that what or how RSE is taught should stay as it is now. The proportion is higher for secondary school parents and whānau (57 percent) than for primary (44 percent).

- Thirteen percent of parents and whānau do not want RSE taught in schools.

Figure 6: Parent and whānau views on whether RSE should be taught, by primary and secondary school

Finding 13: For most RSE topics, parents and whānau broadly agree their child is learning the right amount, but primary school parents more often want sensitive topics taught later.

- More than six in 10 parents and whānau think that the right amount of each individual RSE topic is being taught.

- More than half of primary school parents and whānau want human reproduction (63 percent), gender identity (54 percent), and gender stereotypes (51 percent) covered later because they are concerned about age appropriateness.

Finding 14: Many parents and whānau want their children to learn more about consent, relationships, and health, and learn earlier about friendships, safety, and managing emotions.

- The most common topics that parents and whānau want their children to learn more about are consent (31 percent), romantic relationships (28 percent), and health and contraception (27 percent). The most common topics that parents want their children to learn earlier are friendships and bullying (61 percent), personal safety including online safety (58 percent), and managing feelings and emotions (47 percent), often because they want them to be safe.

Finding 15: Parent and whānau views are split on teaching about gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes.

- Almost a third of parents and whānau want different sexual identities taught earlier and a quarter want it taught more. A quarter want it taught later/less.

- Almost a third of parents and whānau want gender stereotypes taught earlier and a quarter want it taught more. Almost a third want it taught later and a quarter want it taught less.

- A quarter of parents and whānau want gender identity taught earlier and one-fifth want it taught more. A third want it taught later and a quarter want it taught less.

Figure 7: Parent and whānau views on how much gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes should be taught

Finding 16: Parents’ gender, faith, and their children’s identities, impacts how well RSE meets their expectations.

- Mothers are more likely to report their children are learning too little, in particular around consent, managing feelings and emotions, gender stereotypes, and friendships and bullying, because of protective concerns about their children’s safety.

- Fathers are more likely to report that their child is learning too much, particularly around gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes, in line with more traditional values.

- Parents and whānau that practice a faith want less RSE, in particular around gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes, because of concerns that this content does not align with the views outlined in their faith, and that it is the role of their church or faith-based community to teach RSE to their child - especially some of the more sensitive topics.

- Parents and whānau of students from rainbow communities are more likely to want their children to learn about all RSE topics earlier, especially topics on diverse identities and bodies. They want coverage of these topics so that their children can be confident with their body and body image, feel empowered, and feel a sense of belonging by seeing themselves in their learning.

- Parents and whānau of girls want their children to learn about changes to their body and consent earlier, compared to parents and whānau of boys.

Figure 8: Parents and whānau who report they want their children to learn about RSE topics earlier, by whether or not their child identifies as part of rainbow communities

Area 5: Is teaching RSE manageable for schools?

We looked at how school leaders, teachers, and boards are finding the current settings and requirements for RSE teaching.

Finding 17: Most, but not all schools are meeting the current consultation requirement.

- Just over a quarter (28 percent) don’t know they are required to consult at least once every two years and worryingly almost one in 10 board chairs (8 percent) last consulted their community more than two years ago. One-fifth of board chairs (20 percent) don’t know when their school last consulted.

Figure 9: Board chairs report their school last consulted on the health curriculum, including RSE

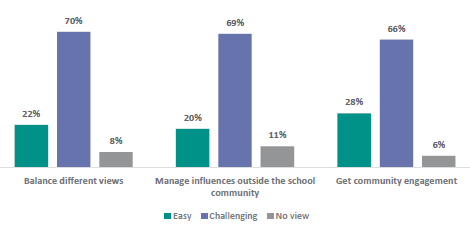

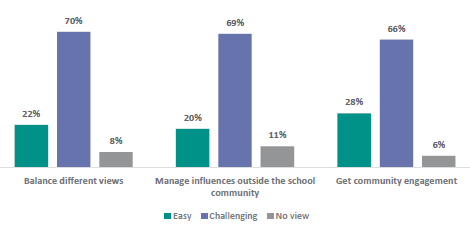

Finding 18: Schools face significant challenges in consulting on what to teach in RSE, particularly rural schools and schools with a high Māori roll.

- Schools find consulting difficult and divisive – almost half of school leaders find consulting challenging or very challenging. In the worst cases, consultation processes result in abuse and aggression.

- New principals find it more challenging (60 percent find it challenging).

- Rural schools find it particularly challenging to maintain relationships with parents and whānau during consultation. Over four in 10 rural schools (44 percent) find maintaining relations challenging, compared to one third of urban schools (34 percent), because consultations often involve the wider community, not only school parents and whānau.

- Around half of schools with a high Māori roll find it challenging to consult with their community (52 percent), because schools often need to consider more carefully how to build trust with whānau Māori and which methods of engagement will work best.

Figure 10: School leader views on how challenging they find aspects of consultation

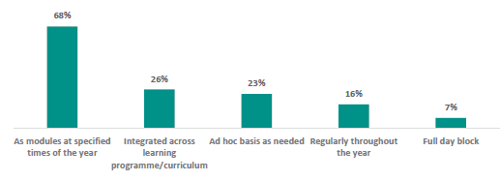

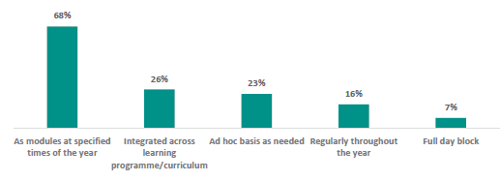

Finding 19: Schools most commonly deliver RSE as modules, but nearly a quarter deliver RSE on an ad-hoc basis.

- Schools have flexibility in how and when they deliver RSE. They can deliver it at any time they want through the year through modules, by integrating it across the curriculum, or as they think it is needed. This means there is variation in the RSE education students receive.

- Only 16 percent of schools deliver RSE lessons regularly throughout the year.

- Twenty-three percent deliver RSE on an ad-hoc basis, as needed.

Figure 11: School leaders report when they deliver RSE lessons at their school

Finding 20: Most, but not all teachers have the capability they need to teach RSE and many find it stressful, particularly in primary.

- Most schools are using teachers from their school to deliver RSE, either exclusively (58 percent) or in combination with external providers (37 percent).

- One in 10 school leaders do not think their teachers have the capability to teach RSE, this rises to one in seven in primary schools.

- Almost one third of teachers find teaching RSE stressful. Teachers in primary school find it more stressful than teachers in secondary school because they usually aren’t subject specialists and because they are often dealing with parents and whānau concerns about what is age appropriate to teach.

Figure 12: Teachers report how stressful they find teaching RSE

Finding 21: Most schools find the Curriculum and RSE guidelines useful.

- Four in five school leaders find the curriculum (79 percent) and RSE guidelines (85 percent) useful for developing their school’s approach to RSE. Teachers who don’t use the RSE guidelines are 1.6 times more likely to be stressed.

Our evaluation led to 21 key findings in five areas:

Area 1: Is teaching RSE in schools supported?

We looked at whether students and parents and whānau support RSE being taught in schools.

Finding 1: There is wide support from students and parents and whānau for RSE being taught in schools.

- Over nine in 10 (91 percent) students support RSE being taught in schools. Girls are more likely to support it being taught, with 95 percent of girls supporting it and 88 percent of boys supporting it.

- Most parents and whānau (87 percent) support RSE being taught in schools.

- Parents and whānau who know what is being taught are happier with RSE.

- Some students d ecide to miss school to avoid RSE (7 percent), but others go to school because they want to learn RSE (9 percent).

Finding 2: Pacific parents, parents of primary aged students, and parents of faith are less supportive.

- Nearly three in 10 (29 percent) Pacific parents and whānau do not support RSE being taught in schools, due to cultural beliefs and reasons to do with their faith. Seventy-one percent do support it.

- Primary school parents and whānau are slightly less supportive (82 percent) than intermediate (89 percent) and secondary school (89 percent) parents and whānau, due to concerns about RSE content being appropriate for their children’s age.

- Parents and whānau who practice a faith are over two times more likely to not support RSE being taught. Over one in five parents who practice a faith (22 percent) do not support RSE being taught, compared to 9 percent of parents who do not practice a faith.

- Six percent of parents and whānau withdraw their child from RSE.

Figure 1: Parents and whānau views on whether RSE should be taught in schools

Area 2: What is being taught in RSE?

Finding 3: What students learn about depends on where they go to school.

- There is a lot of flexibility for schools around exactly which RSE content is taught, and how it is taught. Schools can develop their own programmes, rely on external providers, or both. No RSE content is compulsory, which means what students learn depends entirely on their school.

- RSE teaching across the country includes coverage of a wide range of topics, which relate broadly to personal safety, managing feelings, bodies, health, diverse identities, wellbeing, and relationships with other people.

- Students in girls’ schools are more likely to learn about consent, different sexual identities, and gender identity than students at co-ed schools.

Finding 4: What students are taught changes as they grow up.

- In Years 0-4 (ages 5-8), almost all students learn about feelings and emotions, friendships and bullying, and personal safety. As they progress through years 5-8 (ages 8-12), they begin to learn about getting help with their health and changes to their body.

- At Years 9-10 (ages 12-14), around eight in 10 students learn about consent, romantic relationships, sexual identities, human reproduction, and gender identity.

- Students do not have to learn RSE in Years 11-13 (ages 14-18), but many do.

Finding 5: Sensitive topics are taught later. Different sexual identities, gender identity, and human reproduction are mostly taught in secondary school.

- Less than one in five teachers of students aged 8-10 report teaching sexual identities, gender identity, and human reproduction, compared to three-quarters of teachers of students aged 12-14.

Figure 3: Teachers report human reproduction, gender identity, and different sexual identities are taught at each level

Finding 6: What is taught in RSE is changing over time, as society changes.

- Only around one third of recent school leavers report they learnt about gender identity, gender stereotypes, and celebrating differences, compared to over two-thirds of current Year 11-13 students who report they learn about these topics.

Area 3: Does RSE meet students’ needs?

We looked at how well RSE is meeting the needs of students, and how this differs across different groups.

Finding 7: Most students agree that they are taught the right amount of most RSE topics and at the right age, though some topics aren’t being delivered at the right time to meet students’ needs.

- Across most topics, seven in 10 students say they are being taught the right amount and around half (41-55 percent) agree that they are learning it at the right time.

- Seven in 10 students want to learn about personal safety (including online safety) and friendships and bullying earlier.

- Students think the middle school years are too early for human reproduction learning. Six in 10 of Years 5-6 (60 percent) and half of Years 7-8 students (51 percent) want to learn about human reproduction later.

Figure 4: Students report when they would like to learn about friendships and bullying, and personal safety, including online safety

Finding 8: Boys are more likely to want to learn all topics later than girls, reflecting that boys may go through puberty later.

- Boys are more likely to want to learn all topics later than girls. The most common topics they want to learn about later are human reproduction (35 percent), different sexual identities (22 percent), and romantic relationships including intimate relationships (22 percent).

- Girls often want to learn more and earlier on key topics. Over a quarter of girls want to learn more about managing feelings and emotions (25 percent) and gender stereotypes (31 percent). Over three-quarters of girls want to learn about friendship and bullying (82 percent) and personal safety including online safety (75 percent) earlier.

Finding 9: Students’ views are split about when and how much they learn about human reproduction, different sexual identities, gender identity, and romantic relationships.

- Three in 10 students want to learn about human reproduction earlier (28 percent), and three in 10 want to learn it later (28 percent).

- A third of students want to learn about different sexual identities (33 percent), gender identity (36 percent), and romantic relationships (31 percent) earlier, and nearly one in five want to learn about these subjects later (16-18 percent).

Figure 5: Students report how much they learn about different sexual identities and gender identity

Finding 10: Students’ faith and sexuality impacts how well RSE meets their needs.

- Students of faith are more likely to want to learn less about gender identity and different sexual identities than students who do not practice a faith.

- Secondary school students from rainbow communities want to learn about all RSE topics earlier than other students.

Finding 11: Recent school leavers report that there were significant gaps in their RSE learning.

- Over three-quarters of the students didn’t learn and would have liked to learn about consent (82 percent), managing feelings and emotions (78 percent), personal safety, including online safety (78 percent), and changes to their body (75 percent). This reflects that what they learn depends on schools individual programmes.

Area 4: Does RSE meet the expectations of parents and whānau?

We looked at how well RSE is meeting the needs of parents and whānau, and how this differs across different groups.

Finding 12: A third of parents and whānau want to change what or how RSE is taught, and over one in 10 do not want it taught in schools.

- Thirty-four percent of parents and whānau think that RSE should be taught, but what or how it is taught should change. The proportion is higher for primary school parents and whānau (38 percent) than secondary (32 percent) because they are concerned about RSE content not being age appropriate.

- Fifty-three percent of parents and whānau think that what or how RSE is taught should stay as it is now. The proportion is higher for secondary school parents and whānau (57 percent) than for primary (44 percent).

- Thirteen percent of parents and whānau do not want RSE taught in schools.

Figure 6: Parent and whānau views on whether RSE should be taught, by primary and secondary school

Finding 13: For most RSE topics, parents and whānau broadly agree their child is learning the right amount, but primary school parents more often want sensitive topics taught later.

- More than six in 10 parents and whānau think that the right amount of each individual RSE topic is being taught.

- More than half of primary school parents and whānau want human reproduction (63 percent), gender identity (54 percent), and gender stereotypes (51 percent) covered later because they are concerned about age appropriateness.

Finding 14: Many parents and whānau want their children to learn more about consent, relationships, and health, and learn earlier about friendships, safety, and managing emotions.

- The most common topics that parents and whānau want their children to learn more about are consent (31 percent), romantic relationships (28 percent), and health and contraception (27 percent). The most common topics that parents want their children to learn earlier are friendships and bullying (61 percent), personal safety including online safety (58 percent), and managing feelings and emotions (47 percent), often because they want them to be safe.

Finding 15: Parent and whānau views are split on teaching about gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes.

- Almost a third of parents and whānau want different sexual identities taught earlier and a quarter want it taught more. A quarter want it taught later/less.

- Almost a third of parents and whānau want gender stereotypes taught earlier and a quarter want it taught more. Almost a third want it taught later and a quarter want it taught less.

- A quarter of parents and whānau want gender identity taught earlier and one-fifth want it taught more. A third want it taught later and a quarter want it taught less.

Figure 7: Parent and whānau views on how much gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes should be taught

Finding 16: Parents’ gender, faith, and their children’s identities, impacts how well RSE meets their expectations.

- Mothers are more likely to report their children are learning too little, in particular around consent, managing feelings and emotions, gender stereotypes, and friendships and bullying, because of protective concerns about their children’s safety.

- Fathers are more likely to report that their child is learning too much, particularly around gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes, in line with more traditional values.

- Parents and whānau that practice a faith want less RSE, in particular around gender identity, different sexual identities, and gender stereotypes, because of concerns that this content does not align with the views outlined in their faith, and that it is the role of their church or faith-based community to teach RSE to their child - especially some of the more sensitive topics.

- Parents and whānau of students from rainbow communities are more likely to want their children to learn about all RSE topics earlier, especially topics on diverse identities and bodies. They want coverage of these topics so that their children can be confident with their body and body image, feel empowered, and feel a sense of belonging by seeing themselves in their learning.

- Parents and whānau of girls want their children to learn about changes to their body and consent earlier, compared to parents and whānau of boys.

Figure 8: Parents and whānau who report they want their children to learn about RSE topics earlier, by whether or not their child identifies as part of rainbow communities

Area 5: Is teaching RSE manageable for schools?

We looked at how school leaders, teachers, and boards are finding the current settings and requirements for RSE teaching.

Finding 17: Most, but not all schools are meeting the current consultation requirement.

- Just over a quarter (28 percent) don’t know they are required to consult at least once every two years and worryingly almost one in 10 board chairs (8 percent) last consulted their community more than two years ago. One-fifth of board chairs (20 percent) don’t know when their school last consulted.

Figure 9: Board chairs report their school last consulted on the health curriculum, including RSE

Finding 18: Schools face significant challenges in consulting on what to teach in RSE, particularly rural schools and schools with a high Māori roll.

- Schools find consulting difficult and divisive – almost half of school leaders find consulting challenging or very challenging. In the worst cases, consultation processes result in abuse and aggression.

- New principals find it more challenging (60 percent find it challenging).

- Rural schools find it particularly challenging to maintain relationships with parents and whānau during consultation. Over four in 10 rural schools (44 percent) find maintaining relations challenging, compared to one third of urban schools (34 percent), because consultations often involve the wider community, not only school parents and whānau.

- Around half of schools with a high Māori roll find it challenging to consult with their community (52 percent), because schools often need to consider more carefully how to build trust with whānau Māori and which methods of engagement will work best.

Figure 10: School leader views on how challenging they find aspects of consultation

Finding 19: Schools most commonly deliver RSE as modules, but nearly a quarter deliver RSE on an ad-hoc basis.

- Schools have flexibility in how and when they deliver RSE. They can deliver it at any time they want through the year through modules, by integrating it across the curriculum, or as they think it is needed. This means there is variation in the RSE education students receive.

- Only 16 percent of schools deliver RSE lessons regularly throughout the year.

- Twenty-three percent deliver RSE on an ad-hoc basis, as needed.

Figure 11: School leaders report when they deliver RSE lessons at their school

Finding 20: Most, but not all teachers have the capability they need to teach RSE and many find it stressful, particularly in primary.

- Most schools are using teachers from their school to deliver RSE, either exclusively (58 percent) or in combination with external providers (37 percent).

- One in 10 school leaders do not think their teachers have the capability to teach RSE, this rises to one in seven in primary schools.

- Almost one third of teachers find teaching RSE stressful. Teachers in primary school find it more stressful than teachers in secondary school because they usually aren’t subject specialists and because they are often dealing with parents and whānau concerns about what is age appropriate to teach.

Figure 12: Teachers report how stressful they find teaching RSE

Finding 21: Most schools find the Curriculum and RSE guidelines useful.

- Four in five school leaders find the curriculum (79 percent) and RSE guidelines (85 percent) useful for developing their school’s approach to RSE. Teachers who don’t use the RSE guidelines are 1.6 times more likely to be stressed.

Areas for action

Based on these 21 key findings, ERO has identified seven recommendations, in three areas, that require action to improve RSE and support the impact that it needs to have. These are set out below.

Area 1: Extend teaching and learning of RSE into senior secondary school.

The findings show that RSE is a key area of learning for children and young people, particularly at a time of increased risks through social media and harmful online content.

ERO found widespread support from parents and whānau and students for RSE to be taught in schools. Eighty-seven percent of parents and 91 percent of students support RSE being taught in schools.

However, we also found that students aren’t always getting the content that they need, at the right time for when they need it. We found that boys in particular want to learn about RSE later when key topics become more relevant to them. Boys later maturity means that stopping RSE at Year 10 may be too early. We also heard from young people who have finished secondary school that they did not receive RSE knowledge that they need for their life beyond school.

In the senior secondary school timetables are crowded and students have choice about the subjects they study. But even in this context RSE is too important to leave to chance.

Recommendation 1: RSE continues to be compulsory from Years 1 to 10.

Recommendation 2: The Government consider how to extend RSE teaching and learning into Years 11 to 13 (including whether it should be compulsory), and schools looks at how they can prioritise it.

Area 2: Increase consistency of what is taught.

The findings show that RSE is not being consistently taught across schools. There is variability in what students are taught and when they are taught it depending on where they go to school. This was highlighted in ERO’s previous reviews (2018 and 2007) and remains a problem.

New Zealand’s approach to RSE is significantly less prescriptive than other countries, where there are clearer and consistent national expectations for what will be covered. The flexibility of our curriculum, combined with the autonomy given to individual schools and teachers in delivering RSE, has led to significant variations in the education received by our children and young people.

The challenges our children and young people face are also changing, for example from increased risks of social media and online bullying and abuse. Many parents and students agree on the essential topics they wish to see addressed in RSE at an earlier stage, such as friendships, combating bullying, safety (including online safety), managing emotions, and understanding consent.

ERO has also found that not all teachers are well prepared to teach RSE, particularly in primary schools where RSE is often taught by the classroom teacher. One in three teachers find teaching RSE stressful. It is important all teachers have the skills and support they need.

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education review the relationships and sexuality education (RSE) curriculum (within the Health and Physical Education learning area) to ensure clarity on what should be taught and when, spanning from Years 0 to 13. This review should clarify the knowledge, skills, and understanding students are expected to develop.

Recommendation 4: The Ministry of Education provides evidence based resources and supports for school leaders and teachers, including curriculum and teaching guidance.

Recommendation 5: Teachers, especially those in primary schools, receive the professional development necessary to effectively teach RSE. This support should include training during their initial teacher education, as well as ongoing professional development.

Area 3: Look at the consultation requirement on boards.

ERO has found that the requirement for school boards to consult at least once every two years is creating significant challenges for schools. The increasingly divided views on sensitive topics that are being seen globally are reflected in our findings. On some topics parents and whānau have conflicting views on what should be taught, the extent of that teaching, and the appropriate timing for teaching it. Achieving consensus is frequently difficult, leaving schools caught between opposing perspectives from parents and whānau, as well as external influence from individuals and groups not directly connected to the school. School staff can be subject to ongoing abuse and intimidation. Some schools respond by scaling back RSE teaching, which results in students missing out on learning opportunities.

A more prescriptive curriculum (Recommendation 3) could reduce the need for schools to consult their community as there will be less local variation in what they will teach.

New Zealand is unique in the level of consultation that is required for RSE. The health and physical education learning area is the only part of our national curriculum that mandates consultation at least every two years. Other countries require less or no consultation, instead informing parents about the content and delivery of in-school RSE programmes and allowing them to opt out of lessons if it doesn’t fit their needs. Our study found that parents and whānau do take up the option of withdrawing their children. We also found that the provision of clear information for parents and whānau about what will be taught significantly increases how happy they are with a school’s RSE programme. Parents who know most of what is being taught are most likely to be happy with RSE being taught as it is now (65 percent). Parents who don’t know what is being taught are most likely to disagree that RSE should be taught.

Recommendation 6: Consider replacing the requirement on school boards to consult the school community on RSE (as part of the Health and Physical Education curriculum) with a requirement to inform parents and whānau about what they plan to teach and how they plan to teach it, before they teach it. Schools should continue to take steps to understand students’ needs. Schools should also ensure that parents and whānau know that they can withdraw their children from any element of RSE that they are uncomfortable with.

Recommendation 7: Retain the ability for parents and whānau to withdraw their children from RSE lessons and provide clear information about how to do this.

Based on these 21 key findings, ERO has identified seven recommendations, in three areas, that require action to improve RSE and support the impact that it needs to have. These are set out below.

Area 1: Extend teaching and learning of RSE into senior secondary school.

The findings show that RSE is a key area of learning for children and young people, particularly at a time of increased risks through social media and harmful online content.

ERO found widespread support from parents and whānau and students for RSE to be taught in schools. Eighty-seven percent of parents and 91 percent of students support RSE being taught in schools.

However, we also found that students aren’t always getting the content that they need, at the right time for when they need it. We found that boys in particular want to learn about RSE later when key topics become more relevant to them. Boys later maturity means that stopping RSE at Year 10 may be too early. We also heard from young people who have finished secondary school that they did not receive RSE knowledge that they need for their life beyond school.

In the senior secondary school timetables are crowded and students have choice about the subjects they study. But even in this context RSE is too important to leave to chance.

Recommendation 1: RSE continues to be compulsory from Years 1 to 10.

Recommendation 2: The Government consider how to extend RSE teaching and learning into Years 11 to 13 (including whether it should be compulsory), and schools looks at how they can prioritise it.

Area 2: Increase consistency of what is taught.

The findings show that RSE is not being consistently taught across schools. There is variability in what students are taught and when they are taught it depending on where they go to school. This was highlighted in ERO’s previous reviews (2018 and 2007) and remains a problem.

New Zealand’s approach to RSE is significantly less prescriptive than other countries, where there are clearer and consistent national expectations for what will be covered. The flexibility of our curriculum, combined with the autonomy given to individual schools and teachers in delivering RSE, has led to significant variations in the education received by our children and young people.

The challenges our children and young people face are also changing, for example from increased risks of social media and online bullying and abuse. Many parents and students agree on the essential topics they wish to see addressed in RSE at an earlier stage, such as friendships, combating bullying, safety (including online safety), managing emotions, and understanding consent.

ERO has also found that not all teachers are well prepared to teach RSE, particularly in primary schools where RSE is often taught by the classroom teacher. One in three teachers find teaching RSE stressful. It is important all teachers have the skills and support they need.

Recommendation 3: The Ministry of Education review the relationships and sexuality education (RSE) curriculum (within the Health and Physical Education learning area) to ensure clarity on what should be taught and when, spanning from Years 0 to 13. This review should clarify the knowledge, skills, and understanding students are expected to develop.

Recommendation 4: The Ministry of Education provides evidence based resources and supports for school leaders and teachers, including curriculum and teaching guidance.

Recommendation 5: Teachers, especially those in primary schools, receive the professional development necessary to effectively teach RSE. This support should include training during their initial teacher education, as well as ongoing professional development.

Area 3: Look at the consultation requirement on boards.

ERO has found that the requirement for school boards to consult at least once every two years is creating significant challenges for schools. The increasingly divided views on sensitive topics that are being seen globally are reflected in our findings. On some topics parents and whānau have conflicting views on what should be taught, the extent of that teaching, and the appropriate timing for teaching it. Achieving consensus is frequently difficult, leaving schools caught between opposing perspectives from parents and whānau, as well as external influence from individuals and groups not directly connected to the school. School staff can be subject to ongoing abuse and intimidation. Some schools respond by scaling back RSE teaching, which results in students missing out on learning opportunities.

A more prescriptive curriculum (Recommendation 3) could reduce the need for schools to consult their community as there will be less local variation in what they will teach.

New Zealand is unique in the level of consultation that is required for RSE. The health and physical education learning area is the only part of our national curriculum that mandates consultation at least every two years. Other countries require less or no consultation, instead informing parents about the content and delivery of in-school RSE programmes and allowing them to opt out of lessons if it doesn’t fit their needs. Our study found that parents and whānau do take up the option of withdrawing their children. We also found that the provision of clear information for parents and whānau about what will be taught significantly increases how happy they are with a school’s RSE programme. Parents who know most of what is being taught are most likely to be happy with RSE being taught as it is now (65 percent). Parents who don’t know what is being taught are most likely to disagree that RSE should be taught.

Recommendation 6: Consider replacing the requirement on school boards to consult the school community on RSE (as part of the Health and Physical Education curriculum) with a requirement to inform parents and whānau about what they plan to teach and how they plan to teach it, before they teach it. Schools should continue to take steps to understand students’ needs. Schools should also ensure that parents and whānau know that they can withdraw their children from any element of RSE that they are uncomfortable with.

Recommendation 7: Retain the ability for parents and whānau to withdraw their children from RSE lessons and provide clear information about how to do this.

Want to know more?

To find out more about how RSE is working in our schools, check out our main evaluation report, and insights for school leaders and school boards. These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz.

To find out more about how RSE is working in our schools, check out our main evaluation report, and insights for school leaders and school boards. These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website, www.evidence.ero.govt.nz.

What ERO did

ERO has taken a mixed-methods approach to assess what is and isn’t working in RSE, and why. We focused our investigation on experiences of students, teachers, leaders, school boards, and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand. We ensured that we visited a wide range of schools, including co-educational, girls’ and boys’ schools, rural and urban schools, primary, intermediate, secondary, and area schools, state and state-integrated (including faith-based) schools and schools with high Māori and high Pacific rolls. We visited schools across the country.

In all of ERO’s evaluations, we seek views from a wide range of people. For this study, in addition to speaking with students, parents and whānau, teachers, leaders, and school boards, we invited a wide range of stakeholders to speak with us. We heard from parent groups, external providers of RSE, agencies related to youth mental health, sexual health, and health more broadly, professional teacher associations, cultural and faith-based groups, non-government organisations (NGOs), and advocacy groups.

To help us understand what is happening with RSE in New Zealand, we worked with an Expert Advisory Group which included academics, educators, practitioners and other RSE experts.

Data collected for this report includes:

|

Over 12,000 survey responses from: |

6,470 students 506 recent leavers 700 school leaders 759 teachers 344 board chairs/presiding members 3,809 parents and whānau |

|

Interviews and focus groups with over 300 participants including: |

156 students 42 school leaders 55 teachers 19 board members 38 parents and whānau A range of stakeholders |

|

Site visits at: |

20 English medium schools |

|

Data from: |

An in-depth review of national and international literature In-depth reviews of national and international guidance and policy documents |

We appreciate the work of those who supported this research, particularly the students, parents and whānau, school staff, school boards and experts who shared with us. Their experience and insights are at the heart of what we learnt.

ERO has taken a mixed-methods approach to assess what is and isn’t working in RSE, and why. We focused our investigation on experiences of students, teachers, leaders, school boards, and parents and whānau across Aotearoa New Zealand. We ensured that we visited a wide range of schools, including co-educational, girls’ and boys’ schools, rural and urban schools, primary, intermediate, secondary, and area schools, state and state-integrated (including faith-based) schools and schools with high Māori and high Pacific rolls. We visited schools across the country.

In all of ERO’s evaluations, we seek views from a wide range of people. For this study, in addition to speaking with students, parents and whānau, teachers, leaders, and school boards, we invited a wide range of stakeholders to speak with us. We heard from parent groups, external providers of RSE, agencies related to youth mental health, sexual health, and health more broadly, professional teacher associations, cultural and faith-based groups, non-government organisations (NGOs), and advocacy groups.

To help us understand what is happening with RSE in New Zealand, we worked with an Expert Advisory Group which included academics, educators, practitioners and other RSE experts.

Data collected for this report includes:

|

Over 12,000 survey responses from: |

6,470 students 506 recent leavers 700 school leaders 759 teachers 344 board chairs/presiding members 3,809 parents and whānau |

|

Interviews and focus groups with over 300 participants including: |

156 students 42 school leaders 55 teachers 19 board members 38 parents and whānau A range of stakeholders |

|

Site visits at: |

20 English medium schools |

|

Data from: |

An in-depth review of national and international literature In-depth reviews of national and international guidance and policy documents |

We appreciate the work of those who supported this research, particularly the students, parents and whānau, school staff, school boards and experts who shared with us. Their experience and insights are at the heart of what we learnt.