Related information

You may also be interested in our other reports relating to attendance

Read Online

Introduction

Regular attendance is essential for students to get the most out of school. Lifting attendance is a ‘whole of society’ challenge, but school leaders and teachers play an important and powerful role. The Education Review Office looked at the evidence base and at what leaders and teachers are doing across the country. This guide sets out the most effective actions schools can take to improve attendance – by focusing on the things that have the most impact.

Regular attendance is essential for students to get the most out of school. Lifting attendance is a ‘whole of society’ challenge, but school leaders and teachers play an important and powerful role. The Education Review Office looked at the evidence base and at what leaders and teachers are doing across the country. This guide sets out the most effective actions schools can take to improve attendance – by focusing on the things that have the most impact.

What does this guide cover?

When students are in classrooms as expected, their achievement, wellbeing, and lifelong outcomes are much higher. The more students attend, the more they achieve. Irregular attendance has long-lasting effects on learning because the impact of absence builds over time.

ERO, from the report Back to class – How are attitudes to attendance changing? (2025)

Attendance is closely linked to academic achievement in both primary and secondary schools. The more students attend, the better they perform, including gaining more NCEA credits. Even missing just two days per term can lower their achievement. Students who are otherwise engaged still miss vital learning when absent. Schools that do the best at lifting and maintaining attendance are aspirational and focus deliberately and relentlessly on improving attendance. ERO’s report Back to class: How are attitudes to attendance changing? found out what schools in New Zealand do that has the biggest impact. This good practice guide focuses on doing what works. It outlines the most effective strategies in New Zealand, that are successfully raising attendance.

Who is this guide for?

The Government has set a target that 80 percent of students will be present for more of 90 percent of the term by 2030. This guide is intended to support school leaders, school boards, and classroom teachers to reach this goal.

How to use this guide

Schools are taking a range of actions to improve attendance. To support schools this guide sets out five good practice areas, which have had proven success in New Zealand schools: 1) student belonging 2) clear expectations 3) practical supports 4) rewards 5) patterns of closures. It also sets out case studies of schools that have effectively put in place an end-to-end approach. This good practice guide is supported by findings from the ERO’s national review Back to class: How are attitudes to attendance changing? and acts as a companion resource. You can find the report here: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/ back-to-class-how-are-attitudes-to-attendance-changing-research-report.

This guide links to the Ministry of Education’s guidance to schools on attendance Everyone has a role to play in improving attendance — schools, parents, and Government agencies — and new rules and systems are being introduced to make responsibilities clearer.

From Term 1 2026, all schools will be required to have an Attendance Management Plan. These plans aim to improve student attendance by providing clear pathways to identify and address student absences. When developing and implementing Attendance Management Plans, schools will need to align to the Stepped Attendance Response (STAR) guidance issued by the Ministry of Education. The STAR framework outlines actions at absence thresholds (see the table below), and promotes school-wide approaches to strengthen attendance culture, improve attendance data quality and use, enable timely support and escalation points, and help schools identify what works and which areas need improvement.

- Green (0-4 days missed): School follows up on absences with parents.

- Yellow (5-9 days): School meets with parents to make a plan

- Orange (10-14 days): Support from external services may be needed

- Red (15+ days): The Ministry may step in, including legal action if necessary

The practice areas outlined in this guide give proven examples of strategies that can be used as part of the requirement to report on ‘how we respond’ to attendance.

What is regular attendance?

The current definition for regular attendance is an attendance rate of more than 90 percent. This means a student would miss fewer than five days a term. The Government has set a target of 80 percent of students attending school regularly by 2030. This guide is focused on actions schools can take to increase regular attendance. This guide does not cover actions schools can take for students who are chronically absent – advice on this is in ERO’s 2024 report Left behind: How do we get our chronically absent students back to school?

When students are in classrooms as expected, their achievement, wellbeing, and lifelong outcomes are much higher. The more students attend, the more they achieve. Irregular attendance has long-lasting effects on learning because the impact of absence builds over time.

ERO, from the report Back to class – How are attitudes to attendance changing? (2025)

Attendance is closely linked to academic achievement in both primary and secondary schools. The more students attend, the better they perform, including gaining more NCEA credits. Even missing just two days per term can lower their achievement. Students who are otherwise engaged still miss vital learning when absent. Schools that do the best at lifting and maintaining attendance are aspirational and focus deliberately and relentlessly on improving attendance. ERO’s report Back to class: How are attitudes to attendance changing? found out what schools in New Zealand do that has the biggest impact. This good practice guide focuses on doing what works. It outlines the most effective strategies in New Zealand, that are successfully raising attendance.

Who is this guide for?

The Government has set a target that 80 percent of students will be present for more of 90 percent of the term by 2030. This guide is intended to support school leaders, school boards, and classroom teachers to reach this goal.

How to use this guide

Schools are taking a range of actions to improve attendance. To support schools this guide sets out five good practice areas, which have had proven success in New Zealand schools: 1) student belonging 2) clear expectations 3) practical supports 4) rewards 5) patterns of closures. It also sets out case studies of schools that have effectively put in place an end-to-end approach. This good practice guide is supported by findings from the ERO’s national review Back to class: How are attitudes to attendance changing? and acts as a companion resource. You can find the report here: https://www.evidence.ero.govt.nz/documents/ back-to-class-how-are-attitudes-to-attendance-changing-research-report.

This guide links to the Ministry of Education’s guidance to schools on attendance Everyone has a role to play in improving attendance — schools, parents, and Government agencies — and new rules and systems are being introduced to make responsibilities clearer.

From Term 1 2026, all schools will be required to have an Attendance Management Plan. These plans aim to improve student attendance by providing clear pathways to identify and address student absences. When developing and implementing Attendance Management Plans, schools will need to align to the Stepped Attendance Response (STAR) guidance issued by the Ministry of Education. The STAR framework outlines actions at absence thresholds (see the table below), and promotes school-wide approaches to strengthen attendance culture, improve attendance data quality and use, enable timely support and escalation points, and help schools identify what works and which areas need improvement.

- Green (0-4 days missed): School follows up on absences with parents.

- Yellow (5-9 days): School meets with parents to make a plan

- Orange (10-14 days): Support from external services may be needed

- Red (15+ days): The Ministry may step in, including legal action if necessary

The practice areas outlined in this guide give proven examples of strategies that can be used as part of the requirement to report on ‘how we respond’ to attendance.

What is regular attendance?

The current definition for regular attendance is an attendance rate of more than 90 percent. This means a student would miss fewer than five days a term. The Government has set a target of 80 percent of students attending school regularly by 2030. This guide is focused on actions schools can take to increase regular attendance. This guide does not cover actions schools can take for students who are chronically absent – advice on this is in ERO’s 2024 report Left behind: How do we get our chronically absent students back to school?

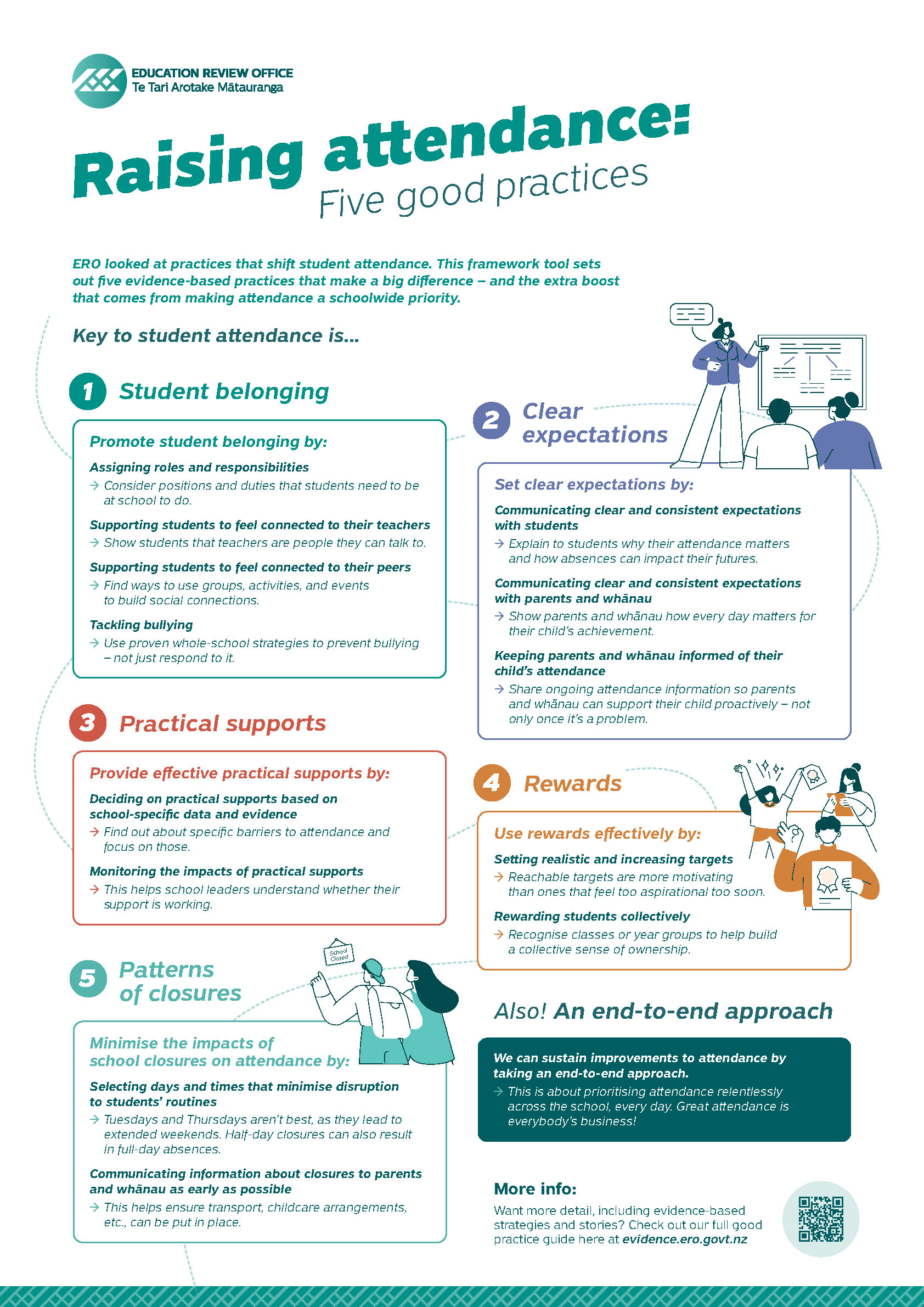

Summary of key practices

PRACTICE 1: STUDENT BELONGING

We can promote student belonging by:

1) assigning roles and responsibilities

2) supporting students to feel connected to their teachers

3) supporting students to feel connected to their peers

4) tackling bullying

PRACTICE 2: CLEAR EXPECTATIONS

We can set clear expectations by:

1) communicating clear and consistent expectations with students

2) communicating clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

3) keeping parents and whānau informed of their child’s attendance.

PRACTICE 3: PRACTICAL SUPPORTS

We can provide effective practical supports by:

1) deciding on practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

2) monitoring the impacts of practical supports. ACT

PRACTICE 4: REWARDS

We can use rewards effectively by:

1) setting realistic and increasing targets

2) rewarding students collectively. ICE

PRACTICE 5: PATTERNS OF CLOSURES

We can minimise the impacts of school closures on attendance by:

1) selecting days and times that minimise disruption to students’ routine

2) communicating information about closures to parents and whānau as early as possible.

AN END-TO-END APPROACH

We can sustain improvements to attendance by taking an end-to–end approach. This is about prioritising attendance relentlessly across the school, every day. .

PRACTICE 1: STUDENT BELONGING

We can promote student belonging by:

1) assigning roles and responsibilities

2) supporting students to feel connected to their teachers

3) supporting students to feel connected to their peers

4) tackling bullying

PRACTICE 2: CLEAR EXPECTATIONS

We can set clear expectations by:

1) communicating clear and consistent expectations with students

2) communicating clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

3) keeping parents and whānau informed of their child’s attendance.

PRACTICE 3: PRACTICAL SUPPORTS

We can provide effective practical supports by:

1) deciding on practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

2) monitoring the impacts of practical supports. ACT

PRACTICE 4: REWARDS

We can use rewards effectively by:

1) setting realistic and increasing targets

2) rewarding students collectively. ICE

PRACTICE 5: PATTERNS OF CLOSURES

We can minimise the impacts of school closures on attendance by:

1) selecting days and times that minimise disruption to students’ routine

2) communicating information about closures to parents and whānau as early as possible.

AN END-TO-END APPROACH

We can sustain improvements to attendance by taking an end-to–end approach. This is about prioritising attendance relentlessly across the school, every day. .

Student belonging

The evidence is clear that supporting students to feel connected

to school has the biggest impact on student attitudes to daily

attendance.

Why does student belonging matter?

Students’ sense of belonging and connectedness to school is critical for attendance, so promoting belonging should be a key part of any attendance plan. This connection is well documented in international research as well as ERO’s national review. When students feel part of a school community, they are more likely to show up, engage, and succeed. A decreased sense of belonging is linked to lower motivation, increased anxiety, and early school dropout. For students from low socio-economic backgrounds, in particular, a sense of belonging is one of the stronger predictors of attendance. In ERO’s review, we found that relationships are one of the strongest motivators for students to go to school. Students often referred to friendships, peer interactions, and social opportunities as motivators for attending school. This is especially important for secondary students, because this is a time when they are particularly focused on their identity and social place.

“Having a strong community helps you want to be part of it. And when you want to be part of it, you’re going to be there, you’re going to show up, you’re going to do the right things. It’s just mostly what pushes me forward is the community and having small form groups where we all know each other quite well.”

- STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

In New Zealand, of all factors tested, belonging has the biggest impact on student attitudes towards the importance of school for their future. Students are over five times more likely to report school is important for their future if they feel they belong.

How can we promote student belonging?

The evidence is clear, to help students feel like they belong, school leaders and teachers can:

1) assign roles and responsibilities

2) support students to feel connected to their teachers

3) support students to feel connected to their peers

4) tackle bullying.

Assigning roles and responsibilities

Students can feel a sense of belonging at school for a range of reasons. One way that students can feel connected to their school is by having a role or responsibility that they need to be there to do. This can include holding leadership roles like prefects, or responsibilities such as road patrol or showing visitors around the school. Students with roles and responsibilities want to attend school to fulfil their duties. Leadership roles that require attendance thresholds can be motivating for students who want them. We found that students with roles and responsibilities want to attend school because they feel pride in fulfilling their duties - they don’t want to let anyone down. For example, we heard from a student with previously poor attendance, who was motivated to attend when she became a school prefect.

“I was given a lot of leadership responsibilities, people started coming up to

me to ask me for help, and now I am a prefect, and I don’t want to be a

prefect that doesn’t come to school.”

- STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

Students in New Zealand are almost twice as likely to think daily attendance is important if they have a role or responsibility at school. Students are also more likely to report that their attitudes to daily attendance have improved in the last year if they have a role or responsibility.

Promoting students’ connection to teachers

The relationship between students and someone on staff at school is another crucial part of their sense of belonging. Ensuring that students have a positive relationship with their teachers or another adult at school has a significant impact on attendance. We heard that students are more likely to attend if they feel that their teacher will notice if they are absent. Alternatively, conflict with a teacher can disrupt a student’s sense of belonging and impact attendance negatively. Form classes and homeroom groups provide a good opportunity for students to form connections with teachers. Teachers can also improve students’ attitudes to attendance by showing an interest in students’ attendance patterns. We heard from students that they felt more accountable when a teacher they respected followed up on their attendance and showed concern.

“The teachers will have one-on-one talks with you if they understand what’s going on... made me feel better. And that made me come to school a bit more.”

STUDENT

Promoting students’ connection to their peers

ERO found that most students (80 percent) report that seeing and spending time with their friends makes them want to go to school. While these relationships occur naturally for many students, this is not always the case. There are steps that teachers and school leaders can take to provide as many opportunities as possible for students to make these connections. Encouraging students to participate in extra-curricular activities and groups is one way to help students maximise their connections. Building social learning activities into the school calendar can also help. School events such as sports days or performing arts events provide structures that help students to connect with others. Having some events or group activities that run across a range of year levels is another way that students can broaden their social connections within the school.

“Before, I wasn’t interested in coming to school. Since I’ve had this class, school wasn’t a place to be bored anymore, I got to get to know a group of students each morning, we weren’t friends before but now we all go out to dinner together. I started to want to come to school to see them.”

- STUDENT

Tackling bullying

A significant barrier to belonging is bullying - this directly affects students’ sense of belonging. Students who experienced bullying behaviour felt less accepted at school and reported enjoying school less. Tackling bullying is critical so that attendance is not impacted by students feeling unsafe at school.

DID YOU KNOW?

13 percent of students reported wanting to miss school because they get bullied or picked on.

Effective schools tackle bullying by taking a consistent, whole-school approach that includes several key actions. They ensure that staff, students, and the wider community share a clear understanding of what constitutes bullying, and that policies and practices are consistently applied. These schools also strengthen their use of data – collecting, analysing, and evaluating bullying incidents and prevention strategies to understand what works and where support is needed. Students are actively involved in shaping prevention efforts through leadership roles and student-led initiatives, which helps build a positive school climate. Additionally, effective schools engage parents and whānau proactively, not just in responding to incidents, but in working together to prevent bullying and promote wellbeing.

Real-life example: Assigning roles and responsibilities

This medium size, urban intermediate school serving a low socio-economic community puts a strong focus on student roles and responsibilities. Students are given opportunities to lead and contribute, such as becoming cultural leaders, monitors, or house representatives. One student shared that being a leader makes them feel responsible to show up: “I’ve got to be there that day because I can’t let people down.” Another student proudly mentioned wearing their ‘Cultural Leader’ badge. Matching roles to students’ interests and strengths is especially motivating for attendance.

This small, urban area school is strengthening student belonging and improving attendance by giving students meaningful roles and responsibilities. Students are also involved in organising and participating in sports events, which are closely tied to attendance expectations.

Other roles are more age specific. In the junior school, Year 6 students become PAWS leaders – Physical Activity Leaders – who run games for younger children, helping them feel connected and valued.

“We’ve just set up PAWS leaders, which is your physical activity leaders. So that gives them something to look forward to – the Year 6 leaders supplying games for the younger kids.”

- TEACHER

Senior students are given the opportunity to take part in a coffee club, where they train as baristas and serve staff, which helps build pride and their relationships with teachers.

“I like making coffee. I make coffee for teachers… Students get trained up on how to make coffee… and then teachers have coffee orders.”

- STUDENT

Real-life example: Supporting students’ connection to peers

This small, rural secondary school has created a morning form class for their students with chronic lateness. This class is staffed by a teacher and focused on providing a time and space for the students to connect with an adult and other students at the start of each day. The teacher takes time to understand their unique challenges and supports them to deal with these. The 14 students enrolled in this class are also supported to form connections with each other and to see themselves as part of a group. The students are also encouraged to engage more widely with the school and there is a strong focus on creating cultural connection.

The meeting space for this morning class is equipped with a small kitchen and the school reached out to a local business to provide breakfast. Students know they can arrive at school and immediately have something to eat. This first hour of every day provides students with a safe space and support to gradually transition, sometimes from a challenging home environment, into the rhythm of school. There have been significant shifts in these students’ attendance patterns, which is helping to lift regular attendance at the school.

This medium size, urban primary school uses the Zones of Regulation framework to help students recognise and manage their emotions, which in turn reduces behavioural incidents and supports positive peer relationships. Teachers explained that “we’re explicitly teaching interpersonal skills, reflections on how we’re feeling and how our responses impact others and ourselves,” and that “kids are learning… they’re all using the same language, they’re all using the same terminology.” One teacher noted:

“The progression of that is first of all noticing how you’re feeling, how that might have an impact on others and yourself, and your learning and your relationships, and then what can I do about it?”

- TEACHER

Students themselves described how this approach helps them “go into a quiet place” or “ask our teacher if you can just go on a walk or something, like take one of your friends,” when they need support. By equipping students with tools to regulate their emotions and resolve conflicts, the Zones of Regulation contribute to a safer, more inclusive environment – factors that encourage regular attendance and strengthen students’ sense of belonging at school.

The Zones of Regulation is an internationally recognised, evidence-based framework designed to help children and adults develop self-regulation skills – meaning the ability to understand and manage their emotions, behaviours, and sensory needs.

The programme uses a simple, colour-coded system to categorise emotions and states of alertness into four zones:

- Blue Zone (low states like sadness or tiredness)

- Green Zone (calm, focused, ready to learn)

- Yellow Zone (heightened states like stress, frustration, or excitement)

- Red Zone (extreme emotions such as anger or panic).

Real-life example: Supporting students’ connection to teachers

This medium size, urban secondary school, serving a low socio-economic community uses ‘whānau rooms’ (homerooms) for Year 9 students. Each student is placed in a small group with a dedicated teacher who remains a consistent point of contact throughout the year. This structure is designed to ensure that every student has at least one trusted adult at school – someone who knows them, notices when they’re absent, and can check in when issues arise.

“Having a teacher who gets you helps you feel safer and more willing to come to school, even when things are hard.”

- STUDENT

Both staff and students report that these relationships make a difference, especially for those who might otherwise feel lost in the transition to secondary school. Students say having “a teacher who gets you” helps them feel safer and more willing to attend, even when other challenges make school difficult. Parents also remark on the value of these connections for their child’s attendance.

“It’s definitely about connection for students, but also teachers. That’s my biggest thing. That’s building connection with students… that’s what keeps us coming.”

- PARENT

Reflective questions:

- How do we know whether individual students are feeling like they belong and are connected to our school community? Who is responsible for monitoring this?

- How might we take action to support isolated students to connect with their peers?

- How might we better use roles and responsibilities more purposefully to maximise students’ motivation to be at school?

- How can we support teachers and other staff to grow relationships with students that enable students to feel a sense of belonging?

- Can we identify where bullying is a barrier to attendance and address it?

The evidence is clear that supporting students to feel connected

to school has the biggest impact on student attitudes to daily

attendance.

Why does student belonging matter?

Students’ sense of belonging and connectedness to school is critical for attendance, so promoting belonging should be a key part of any attendance plan. This connection is well documented in international research as well as ERO’s national review. When students feel part of a school community, they are more likely to show up, engage, and succeed. A decreased sense of belonging is linked to lower motivation, increased anxiety, and early school dropout. For students from low socio-economic backgrounds, in particular, a sense of belonging is one of the stronger predictors of attendance. In ERO’s review, we found that relationships are one of the strongest motivators for students to go to school. Students often referred to friendships, peer interactions, and social opportunities as motivators for attending school. This is especially important for secondary students, because this is a time when they are particularly focused on their identity and social place.

“Having a strong community helps you want to be part of it. And when you want to be part of it, you’re going to be there, you’re going to show up, you’re going to do the right things. It’s just mostly what pushes me forward is the community and having small form groups where we all know each other quite well.”

- STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

In New Zealand, of all factors tested, belonging has the biggest impact on student attitudes towards the importance of school for their future. Students are over five times more likely to report school is important for their future if they feel they belong.

How can we promote student belonging?

The evidence is clear, to help students feel like they belong, school leaders and teachers can:

1) assign roles and responsibilities

2) support students to feel connected to their teachers

3) support students to feel connected to their peers

4) tackle bullying.

Assigning roles and responsibilities

Students can feel a sense of belonging at school for a range of reasons. One way that students can feel connected to their school is by having a role or responsibility that they need to be there to do. This can include holding leadership roles like prefects, or responsibilities such as road patrol or showing visitors around the school. Students with roles and responsibilities want to attend school to fulfil their duties. Leadership roles that require attendance thresholds can be motivating for students who want them. We found that students with roles and responsibilities want to attend school because they feel pride in fulfilling their duties - they don’t want to let anyone down. For example, we heard from a student with previously poor attendance, who was motivated to attend when she became a school prefect.

“I was given a lot of leadership responsibilities, people started coming up to

me to ask me for help, and now I am a prefect, and I don’t want to be a

prefect that doesn’t come to school.”

- STUDENT

DID YOU KNOW?

Students in New Zealand are almost twice as likely to think daily attendance is important if they have a role or responsibility at school. Students are also more likely to report that their attitudes to daily attendance have improved in the last year if they have a role or responsibility.

Promoting students’ connection to teachers

The relationship between students and someone on staff at school is another crucial part of their sense of belonging. Ensuring that students have a positive relationship with their teachers or another adult at school has a significant impact on attendance. We heard that students are more likely to attend if they feel that their teacher will notice if they are absent. Alternatively, conflict with a teacher can disrupt a student’s sense of belonging and impact attendance negatively. Form classes and homeroom groups provide a good opportunity for students to form connections with teachers. Teachers can also improve students’ attitudes to attendance by showing an interest in students’ attendance patterns. We heard from students that they felt more accountable when a teacher they respected followed up on their attendance and showed concern.

“The teachers will have one-on-one talks with you if they understand what’s going on... made me feel better. And that made me come to school a bit more.”

STUDENT

Promoting students’ connection to their peers

ERO found that most students (80 percent) report that seeing and spending time with their friends makes them want to go to school. While these relationships occur naturally for many students, this is not always the case. There are steps that teachers and school leaders can take to provide as many opportunities as possible for students to make these connections. Encouraging students to participate in extra-curricular activities and groups is one way to help students maximise their connections. Building social learning activities into the school calendar can also help. School events such as sports days or performing arts events provide structures that help students to connect with others. Having some events or group activities that run across a range of year levels is another way that students can broaden their social connections within the school.

“Before, I wasn’t interested in coming to school. Since I’ve had this class, school wasn’t a place to be bored anymore, I got to get to know a group of students each morning, we weren’t friends before but now we all go out to dinner together. I started to want to come to school to see them.”

- STUDENT

Tackling bullying

A significant barrier to belonging is bullying - this directly affects students’ sense of belonging. Students who experienced bullying behaviour felt less accepted at school and reported enjoying school less. Tackling bullying is critical so that attendance is not impacted by students feeling unsafe at school.

DID YOU KNOW?

13 percent of students reported wanting to miss school because they get bullied or picked on.

Effective schools tackle bullying by taking a consistent, whole-school approach that includes several key actions. They ensure that staff, students, and the wider community share a clear understanding of what constitutes bullying, and that policies and practices are consistently applied. These schools also strengthen their use of data – collecting, analysing, and evaluating bullying incidents and prevention strategies to understand what works and where support is needed. Students are actively involved in shaping prevention efforts through leadership roles and student-led initiatives, which helps build a positive school climate. Additionally, effective schools engage parents and whānau proactively, not just in responding to incidents, but in working together to prevent bullying and promote wellbeing.

Real-life example: Assigning roles and responsibilities

This medium size, urban intermediate school serving a low socio-economic community puts a strong focus on student roles and responsibilities. Students are given opportunities to lead and contribute, such as becoming cultural leaders, monitors, or house representatives. One student shared that being a leader makes them feel responsible to show up: “I’ve got to be there that day because I can’t let people down.” Another student proudly mentioned wearing their ‘Cultural Leader’ badge. Matching roles to students’ interests and strengths is especially motivating for attendance.

This small, urban area school is strengthening student belonging and improving attendance by giving students meaningful roles and responsibilities. Students are also involved in organising and participating in sports events, which are closely tied to attendance expectations.

Other roles are more age specific. In the junior school, Year 6 students become PAWS leaders – Physical Activity Leaders – who run games for younger children, helping them feel connected and valued.

“We’ve just set up PAWS leaders, which is your physical activity leaders. So that gives them something to look forward to – the Year 6 leaders supplying games for the younger kids.”

- TEACHER

Senior students are given the opportunity to take part in a coffee club, where they train as baristas and serve staff, which helps build pride and their relationships with teachers.

“I like making coffee. I make coffee for teachers… Students get trained up on how to make coffee… and then teachers have coffee orders.”

- STUDENT

Real-life example: Supporting students’ connection to peers

This small, rural secondary school has created a morning form class for their students with chronic lateness. This class is staffed by a teacher and focused on providing a time and space for the students to connect with an adult and other students at the start of each day. The teacher takes time to understand their unique challenges and supports them to deal with these. The 14 students enrolled in this class are also supported to form connections with each other and to see themselves as part of a group. The students are also encouraged to engage more widely with the school and there is a strong focus on creating cultural connection.

The meeting space for this morning class is equipped with a small kitchen and the school reached out to a local business to provide breakfast. Students know they can arrive at school and immediately have something to eat. This first hour of every day provides students with a safe space and support to gradually transition, sometimes from a challenging home environment, into the rhythm of school. There have been significant shifts in these students’ attendance patterns, which is helping to lift regular attendance at the school.

This medium size, urban primary school uses the Zones of Regulation framework to help students recognise and manage their emotions, which in turn reduces behavioural incidents and supports positive peer relationships. Teachers explained that “we’re explicitly teaching interpersonal skills, reflections on how we’re feeling and how our responses impact others and ourselves,” and that “kids are learning… they’re all using the same language, they’re all using the same terminology.” One teacher noted:

“The progression of that is first of all noticing how you’re feeling, how that might have an impact on others and yourself, and your learning and your relationships, and then what can I do about it?”

- TEACHER

Students themselves described how this approach helps them “go into a quiet place” or “ask our teacher if you can just go on a walk or something, like take one of your friends,” when they need support. By equipping students with tools to regulate their emotions and resolve conflicts, the Zones of Regulation contribute to a safer, more inclusive environment – factors that encourage regular attendance and strengthen students’ sense of belonging at school.

The Zones of Regulation is an internationally recognised, evidence-based framework designed to help children and adults develop self-regulation skills – meaning the ability to understand and manage their emotions, behaviours, and sensory needs.

The programme uses a simple, colour-coded system to categorise emotions and states of alertness into four zones:

- Blue Zone (low states like sadness or tiredness)

- Green Zone (calm, focused, ready to learn)

- Yellow Zone (heightened states like stress, frustration, or excitement)

- Red Zone (extreme emotions such as anger or panic).

Real-life example: Supporting students’ connection to teachers

This medium size, urban secondary school, serving a low socio-economic community uses ‘whānau rooms’ (homerooms) for Year 9 students. Each student is placed in a small group with a dedicated teacher who remains a consistent point of contact throughout the year. This structure is designed to ensure that every student has at least one trusted adult at school – someone who knows them, notices when they’re absent, and can check in when issues arise.

“Having a teacher who gets you helps you feel safer and more willing to come to school, even when things are hard.”

- STUDENT

Both staff and students report that these relationships make a difference, especially for those who might otherwise feel lost in the transition to secondary school. Students say having “a teacher who gets you” helps them feel safer and more willing to attend, even when other challenges make school difficult. Parents also remark on the value of these connections for their child’s attendance.

“It’s definitely about connection for students, but also teachers. That’s my biggest thing. That’s building connection with students… that’s what keeps us coming.”

- PARENT

Reflective questions:

- How do we know whether individual students are feeling like they belong and are connected to our school community? Who is responsible for monitoring this?

- How might we take action to support isolated students to connect with their peers?

- How might we better use roles and responsibilities more purposefully to maximise students’ motivation to be at school?

- How can we support teachers and other staff to grow relationships with students that enable students to feel a sense of belonging?

- Can we identify where bullying is a barrier to attendance and address it?

Clear expectations

Setting and communicating clear expectations about attendance targets has a significant impact on improving attendance patterns.

Why do clear expectations matter?

Establishing clear expectations supports student engagement and attendance. Messaging from school leaders and teachers set the scene for how students, parents and whānau think about attendance. We found that students who feel like their school expects them to attend regularly are also more likely to view daily attendance as important for their future. This is true for both primary and secondary school students and parents.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools set clear expectations about regular attendance, parents are twice as likely to view daily attendance as important for their child’s future.

How can we set clear expectations?

To lift regular attendance through setting clear expectations, school leaders and teachers need to:

1) communicate clear and consistent expectations with students

2) communicate clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

3) keep parents informed of their child’s attendance.

Communicating clear and consistent expectations with students

Students respond well to explicit teaching about the impacts of absence over time. It’s important to make sure students understand the reason for attendance monitoring and why the school takes it so seriously. This could include clearly explaining to students how one-off absences build up over time, which helps them to understand the importance of daily attendance. Schools can also motivate students by showing how absenteeism has lifelong impacts, like earning lower income. We heard students clearly articulate why they need to attend school and how they are making an effort to attend more regularly.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools set clear expectations about regular attendance, students are more than twice as likely to view daily attendance as important, and to see school as important for their future.

“If you miss one week of school each year it adds up to significant numbers… I didn’t think it would be that many days… [It makes me think] there’s not really a point to take a day off school just because I’m tired.”

- STUDENT

Students also respond well to seeing their own attendance data in relation to a set target. Once they understand what the goal is and why, they are motivated by seeing exactly where they are in relation to that goal. Schools that perform well on attendance are communicating this information to students at every level, at every opportunity. Teachers reinforce messaging in their classrooms, and school leaders reinforce messaging through events like school assemblies.

Communicating clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

Parents and whānau need to know about the impacts of absences so that they don’t write off occasional absences as unimportant. Expectations are most effective when they are explained as part of a broader purpose, such as preparing students for work, or contributing to a team or whole school attendance goal. Providing evidence about the impact of absences on lifelong outcomes is also valuable for students, parents and whānau to understand why attendance is important.

ERO also found that parents report increased belief in the importance of daily attendance when school messaging clearly explains the legal obligations of parents to ensure their child attends school. Some parents report that they would like clearer guidance on what warrants a ‘sick day’ – they sometimes report conflicting messages from school leadership and classroom teachers.

Schools can reinforce attendance expectations through messaging on school websites, newsletters, and social media. Another way schools do this is through direct, targeted engagement with parents themselves. This happens at parent information evenings, at school drop-offs and pick-ups, and through follow-up phone calls about recent student absences.

“Family could see the impact that it had… 80 percent means missing (nearly) a quarter of classes.”

- SCHOOL LEADER

“There is relatively good communication with us about attendance, achievement, learning success, and strong links between attending school and achievement success are regularly reinforced, through newsletters and social media. I believe that the school is doing everything possible to encourage positive attendance patterns.”

- PARENT

DID YOU KNOW?

In New Zealand, parents report feeling less comfortable with their child missing a week or more of school due to school messaging around the importance of attendance. Since 2022, the proportion of parents who are comfortable for their child to miss a week or more of school has decreased by 10 percentage points.

Keep parents informed of their child’s attendance

Parents appreciate early and proactive communication when attendance issues arise. Parents of secondary students might not know when their child has missed classes. Information from the school reduces guesswork and helps parents have informed conversations with their child. Some parents respond best to formal letters from the school, while others said the regular attendance reports, regardless of concerns, helps them understand patterns and avoid surprises.

Detailed weekly reports create a sense of accountability and help parents be proactive. Seeing a drop in their child’s attendance before a formal letter arrives, gives them a chance to address it early. Attendance apps can also provide daily updates, which some parents will check while they are at work. However, inaccurate attendance data can have negative impacts – parents can become frustrated and lose faith in the school’s messaging.

“My daughter, this year has been inclined to miss a class or two. That’s why we’re cracking down quite hard, and why I’m pleased that the school is so proactive in letting us know if she is late for anything or not attending.”

- PARENT

Following up on every absence by contacting parents to find out why their child is not at school has a significant positive impact on attendance. It reinforces the expectation that students need to be at school every day.

Administrative staff, rather than teachers, often play a valued central role in tracking and following up on absences after student rolls have been taken. This makes sense as administrative staff usually receive the calls from parents when their child is going to be absent for sickness or other reasons. If the school doesn’t know why a student is absent, they call home to find out.

Primary parents told us how the anticipation of a call from school staff can make them think twice about absences, especially if they have a good relationship with the school. We also heard that following up on absences highlights to parents that the school cares about their child, especially if the conversations are focused on what the student or family needs to help them improve attendance.

DID YOU KNOW?

Primary school parents are twice as likely to report their child attends school regularly if the school contacts them on any day their child is absent, when the school doesn’t know why.

What does this look like in practice?

Real-life examples: Communicate clear and consistent expectations with students

One urban primary school in a low socio-economic community has improved attendance through consistent and explicit messaging around the impacts of absenteeism on achievement and life outcomes. They have attendance as a standing item on their school assembly agenda. Every week at assembly they revisit the importance of daily attendance, share how the attendance data is tracking within the school, and then move on to awarding points to the groups that have high attendance. (See part 4 of this guide for more about collective rewards).

We heard about students receiving direct messaging about attendance through classroom lessons, notices, and weekly emails. Attendance is embedded into the schools’ PB4L (Positive Behaviour for Learning) frameworks, with themes like punctuality and participation are reinforced through curriculum content and class culture practices.

Real-life example: Communicate clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

This medium sized, urban intermediate school makes expectations about attendance clear to parents through a range of channels, including social media. One parent noted seeing messaging on the school’s Facebook page about a new attendance initiative tied to house points and tokens. Parents learning about the school’s use of thresholds and rewards can support wider messages and reinforce what their child is telling them: “I’ve got to be at school before 8:30, Mum, because I need to get my token,” so everyone is working together to improve attendance.

Real-life example: Keep parents informed of their child’s attendance

Some schools are providing more regular reporting about attendance and with increasing detail. Providing these reports alongside academic reports sends a message to parents that attendance and learning progress are both important.

“We receive on Friday after school, an attendance and academic report. I’ve never received them at other schools… So interesting and new. And they have attendance down to lateness, and they break that up with absences from home class and home groups… even to each subject.”

- SECONDARY PARENT

We heard that a range of communication tools, such as school apps (e.g. Hero, School Loop) help keep attendance front of mind. These allow parents to monitor attendance in real time and receive immediate alerts for unexplained absences. These systems have created a feedback loop that reinforces parental responsibility and encourages prompt action. Parents described how seeing their child’s attendance percentage made it a measurable priority.

“It’s made me think like, ‘Oh, I don’t want their number to drop down below where it should be’.”

- PRIMARY PARENT

Example from overseas: communication with parents

One school in Queensland has been using a traffic light system to show when attendance is within a certain range. The colour-coding makes it easy for parents and students to see when attendance levels are on track or concerning.

Reflective questions:

- How consistently are expectations around attendance communicated across all levels of our school – from leadership to classroom teachers?

- Do our students and parents understand not just what the attendance expectations are, but why they matter for their learning and future? How do we know?

- In what ways are we making attendance data visible and meaningful to students, parents and whānau to help them track attendance and progress toward attendance goals?

Setting and communicating clear expectations about attendance targets has a significant impact on improving attendance patterns.

Why do clear expectations matter?

Establishing clear expectations supports student engagement and attendance. Messaging from school leaders and teachers set the scene for how students, parents and whānau think about attendance. We found that students who feel like their school expects them to attend regularly are also more likely to view daily attendance as important for their future. This is true for both primary and secondary school students and parents.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools set clear expectations about regular attendance, parents are twice as likely to view daily attendance as important for their child’s future.

How can we set clear expectations?

To lift regular attendance through setting clear expectations, school leaders and teachers need to:

1) communicate clear and consistent expectations with students

2) communicate clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

3) keep parents informed of their child’s attendance.

Communicating clear and consistent expectations with students

Students respond well to explicit teaching about the impacts of absence over time. It’s important to make sure students understand the reason for attendance monitoring and why the school takes it so seriously. This could include clearly explaining to students how one-off absences build up over time, which helps them to understand the importance of daily attendance. Schools can also motivate students by showing how absenteeism has lifelong impacts, like earning lower income. We heard students clearly articulate why they need to attend school and how they are making an effort to attend more regularly.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools set clear expectations about regular attendance, students are more than twice as likely to view daily attendance as important, and to see school as important for their future.

“If you miss one week of school each year it adds up to significant numbers… I didn’t think it would be that many days… [It makes me think] there’s not really a point to take a day off school just because I’m tired.”

- STUDENT

Students also respond well to seeing their own attendance data in relation to a set target. Once they understand what the goal is and why, they are motivated by seeing exactly where they are in relation to that goal. Schools that perform well on attendance are communicating this information to students at every level, at every opportunity. Teachers reinforce messaging in their classrooms, and school leaders reinforce messaging through events like school assemblies.

Communicating clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

Parents and whānau need to know about the impacts of absences so that they don’t write off occasional absences as unimportant. Expectations are most effective when they are explained as part of a broader purpose, such as preparing students for work, or contributing to a team or whole school attendance goal. Providing evidence about the impact of absences on lifelong outcomes is also valuable for students, parents and whānau to understand why attendance is important.

ERO also found that parents report increased belief in the importance of daily attendance when school messaging clearly explains the legal obligations of parents to ensure their child attends school. Some parents report that they would like clearer guidance on what warrants a ‘sick day’ – they sometimes report conflicting messages from school leadership and classroom teachers.

Schools can reinforce attendance expectations through messaging on school websites, newsletters, and social media. Another way schools do this is through direct, targeted engagement with parents themselves. This happens at parent information evenings, at school drop-offs and pick-ups, and through follow-up phone calls about recent student absences.

“Family could see the impact that it had… 80 percent means missing (nearly) a quarter of classes.”

- SCHOOL LEADER

“There is relatively good communication with us about attendance, achievement, learning success, and strong links between attending school and achievement success are regularly reinforced, through newsletters and social media. I believe that the school is doing everything possible to encourage positive attendance patterns.”

- PARENT

DID YOU KNOW?

In New Zealand, parents report feeling less comfortable with their child missing a week or more of school due to school messaging around the importance of attendance. Since 2022, the proportion of parents who are comfortable for their child to miss a week or more of school has decreased by 10 percentage points.

Keep parents informed of their child’s attendance

Parents appreciate early and proactive communication when attendance issues arise. Parents of secondary students might not know when their child has missed classes. Information from the school reduces guesswork and helps parents have informed conversations with their child. Some parents respond best to formal letters from the school, while others said the regular attendance reports, regardless of concerns, helps them understand patterns and avoid surprises.

Detailed weekly reports create a sense of accountability and help parents be proactive. Seeing a drop in their child’s attendance before a formal letter arrives, gives them a chance to address it early. Attendance apps can also provide daily updates, which some parents will check while they are at work. However, inaccurate attendance data can have negative impacts – parents can become frustrated and lose faith in the school’s messaging.

“My daughter, this year has been inclined to miss a class or two. That’s why we’re cracking down quite hard, and why I’m pleased that the school is so proactive in letting us know if she is late for anything or not attending.”

- PARENT

Following up on every absence by contacting parents to find out why their child is not at school has a significant positive impact on attendance. It reinforces the expectation that students need to be at school every day.

Administrative staff, rather than teachers, often play a valued central role in tracking and following up on absences after student rolls have been taken. This makes sense as administrative staff usually receive the calls from parents when their child is going to be absent for sickness or other reasons. If the school doesn’t know why a student is absent, they call home to find out.

Primary parents told us how the anticipation of a call from school staff can make them think twice about absences, especially if they have a good relationship with the school. We also heard that following up on absences highlights to parents that the school cares about their child, especially if the conversations are focused on what the student or family needs to help them improve attendance.

DID YOU KNOW?

Primary school parents are twice as likely to report their child attends school regularly if the school contacts them on any day their child is absent, when the school doesn’t know why.

What does this look like in practice?

Real-life examples: Communicate clear and consistent expectations with students

One urban primary school in a low socio-economic community has improved attendance through consistent and explicit messaging around the impacts of absenteeism on achievement and life outcomes. They have attendance as a standing item on their school assembly agenda. Every week at assembly they revisit the importance of daily attendance, share how the attendance data is tracking within the school, and then move on to awarding points to the groups that have high attendance. (See part 4 of this guide for more about collective rewards).

We heard about students receiving direct messaging about attendance through classroom lessons, notices, and weekly emails. Attendance is embedded into the schools’ PB4L (Positive Behaviour for Learning) frameworks, with themes like punctuality and participation are reinforced through curriculum content and class culture practices.

Real-life example: Communicate clear and consistent expectations with parents and whānau

This medium sized, urban intermediate school makes expectations about attendance clear to parents through a range of channels, including social media. One parent noted seeing messaging on the school’s Facebook page about a new attendance initiative tied to house points and tokens. Parents learning about the school’s use of thresholds and rewards can support wider messages and reinforce what their child is telling them: “I’ve got to be at school before 8:30, Mum, because I need to get my token,” so everyone is working together to improve attendance.

Real-life example: Keep parents informed of their child’s attendance

Some schools are providing more regular reporting about attendance and with increasing detail. Providing these reports alongside academic reports sends a message to parents that attendance and learning progress are both important.

“We receive on Friday after school, an attendance and academic report. I’ve never received them at other schools… So interesting and new. And they have attendance down to lateness, and they break that up with absences from home class and home groups… even to each subject.”

- SECONDARY PARENT

We heard that a range of communication tools, such as school apps (e.g. Hero, School Loop) help keep attendance front of mind. These allow parents to monitor attendance in real time and receive immediate alerts for unexplained absences. These systems have created a feedback loop that reinforces parental responsibility and encourages prompt action. Parents described how seeing their child’s attendance percentage made it a measurable priority.

“It’s made me think like, ‘Oh, I don’t want their number to drop down below where it should be’.”

- PRIMARY PARENT

Example from overseas: communication with parents

One school in Queensland has been using a traffic light system to show when attendance is within a certain range. The colour-coding makes it easy for parents and students to see when attendance levels are on track or concerning.

Reflective questions:

- How consistently are expectations around attendance communicated across all levels of our school – from leadership to classroom teachers?

- Do our students and parents understand not just what the attendance expectations are, but why they matter for their learning and future? How do we know?

- In what ways are we making attendance data visible and meaningful to students, parents and whānau to help them track attendance and progress toward attendance goals?

Practical supports

Students’ attendance and attitudes towards attendance are better when schools take action to reduce barriers.

Why does providing practical supports matter?

Providing practical supports can build and reinforce a sense of belonging, which we already know is an important factor for attendance and attitudes. When teachers and school leaders work alongside parents and whānau to support their needs, it makes students feel cared for. In our review, we heard that parents deeply appreciate practical support, especially in lower socio-economic contexts.

The evidence base shows that there are no ‘one-size-fits-all’ practical supports that will be impactful at all schools. Instead, it is key for each school to consider supports that respond directly to the attendance barriers of their students and their families. Practical supports are often critical enablers of attendance, especially for families facing hardship. ERO’s research also found that secondary students are most impacted by the ‘shame’ of practical barriers to attendance, because of peer pressure for adolescents. This may explain why practical supports have the most positive impacts for secondary parents.

DID YOU KNOW?

Students are more than twice as likely to think daily attendance is important if the school is providing practical supports. Parents are nearly one and a half times more likely to report their attitudes to daily attendance have improved in the last year if the school is providing practical supports.

How can we use practical supports to improve daily attendance?

To improve attendance through the provision of practical supports, school leaders and teachers need to:

1) decide on practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

2) monitor the impacts of practical supports.

Decide on practical supports based on evidence

The provision of practical supports needs to be targeted and tailored for individual needs. It is vital that school leaders or teachers take the time to understand what the specific barriers are for their students. Many schools make a point of asking parents and whānau, “How can we support you to improve your child’s attendance?” This is their first point of conversation about attendance. This removes the sense of blame and provides an opportunity to hear about that child’s unique barriers. Providing supports that don’t draw attention to this hardship works best for students.

Support with uniforms helps students feel included, and can reduce stress or embarrassment. Providing food can motivate students to attend, especially when the food is enjoyable. We heard a lot about ‘hot chip lunches’ and ‘pizza day’ being incentives to attend. Providing food can also make school feel more welcoming – food is perceived to be nurturing as part of a wider system of care. Transport to help students get to school – either with the help of a school van or school bus – is especially important for secondary students who typically have to make their own way there. As with food, transport isn’t only a ‘practical’ support – it makes students feel cared for.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools provide practical supports, students are more than twice as likely to think that school is important for their future. Secondary school parents are nearly twice as likely to view daily attendance as important when a school provides practical supports.

“I think the difference [that improved attendance at my child’s school] is that they’re so whānau centred, so community centred. Not everyone’s equipped with what they need to get to school or to do well at school, so bringing it back to how we can help within the family system makes a real change.”

- PARENT

Monitor the impacts of practical supports

It is important to track the impact that a practical intervention has on a students’ attendance and not just assume that attendance improves. The wider evidence on providing practical supports, such as transport, food, or clothing, affirms that they are not instant solutions – they are most effective when part of a wider approach. Teachers and school leaders need to monitor attendance data to see if a shift in attendance patterns has occurred. If there is little or no shift, then it is important to follow up with students, parents and whānau to discuss if additional or different supports.

What does this look like in practice?

Real-life example: Providing practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

At one small area school, we heard that the neighbourhood buses make a big difference for this school’s families. The provision of transport is especially important for students who live further way, who struggle with routine, or whose parents are unable to provide transport due to work commitments.

“I go on the bus on Fridays… my mum goes to work at the same time”

- STUDENT

We also spoke to some primary schools which have arranged walking buses, which can be especially helpful for working parents and families with siblings at different schools.

In one urban secondary school, uniforms are subsidised by a trust board. Students also support each other by sharing spare uniform items. For example, one student regularly brought extra uniform pieces just in case, to help peers avoid consequences.

As well as uniform support, transport costs are covered for students who live far away, and food is provided daily. Staff and parents note that students who might otherwise struggle to attend are enabled through these practical supports.

Some schools are working with local charities to help with practical supports to help students to attend. Schools told us that the KidsCan programme helps them provide coats and shoes. Some schools also have fundraising events. We heard that lack of warm and protective clothing is a particular challenge for attendance in winter. One small primary school in an urban area told us that food is sourced from local supermarket donations, such as bread rolls nearing expiry, and that these are distributed to families or used to prepare meals for students. The school keeps food in the freezer and staff will make toasties or sandwiches as needed.

“We can always find some sandwich. We can always make someone something.”

- TEACHER

Reflective questions

- How well do we understand the specific, practical barriers to attendance faced by students and families in our school community?

- What processes do we have in place to engage with parents and whānau in a way that invites open conversation about attendance challenges without blame, or shame?

- How do we use attendance data to inform decisions, and to monitor and adapt if those supports don’t lead to improved attendance?

- How can we access resources and support from our community, for example, charities or community groups, to help families overcome practical barriers?

Students’ attendance and attitudes towards attendance are better when schools take action to reduce barriers.

Why does providing practical supports matter?

Providing practical supports can build and reinforce a sense of belonging, which we already know is an important factor for attendance and attitudes. When teachers and school leaders work alongside parents and whānau to support their needs, it makes students feel cared for. In our review, we heard that parents deeply appreciate practical support, especially in lower socio-economic contexts.

The evidence base shows that there are no ‘one-size-fits-all’ practical supports that will be impactful at all schools. Instead, it is key for each school to consider supports that respond directly to the attendance barriers of their students and their families. Practical supports are often critical enablers of attendance, especially for families facing hardship. ERO’s research also found that secondary students are most impacted by the ‘shame’ of practical barriers to attendance, because of peer pressure for adolescents. This may explain why practical supports have the most positive impacts for secondary parents.

DID YOU KNOW?

Students are more than twice as likely to think daily attendance is important if the school is providing practical supports. Parents are nearly one and a half times more likely to report their attitudes to daily attendance have improved in the last year if the school is providing practical supports.

How can we use practical supports to improve daily attendance?

To improve attendance through the provision of practical supports, school leaders and teachers need to:

1) decide on practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

2) monitor the impacts of practical supports.

Decide on practical supports based on evidence

The provision of practical supports needs to be targeted and tailored for individual needs. It is vital that school leaders or teachers take the time to understand what the specific barriers are for their students. Many schools make a point of asking parents and whānau, “How can we support you to improve your child’s attendance?” This is their first point of conversation about attendance. This removes the sense of blame and provides an opportunity to hear about that child’s unique barriers. Providing supports that don’t draw attention to this hardship works best for students.

Support with uniforms helps students feel included, and can reduce stress or embarrassment. Providing food can motivate students to attend, especially when the food is enjoyable. We heard a lot about ‘hot chip lunches’ and ‘pizza day’ being incentives to attend. Providing food can also make school feel more welcoming – food is perceived to be nurturing as part of a wider system of care. Transport to help students get to school – either with the help of a school van or school bus – is especially important for secondary students who typically have to make their own way there. As with food, transport isn’t only a ‘practical’ support – it makes students feel cared for.

DID YOU KNOW?

When schools provide practical supports, students are more than twice as likely to think that school is important for their future. Secondary school parents are nearly twice as likely to view daily attendance as important when a school provides practical supports.

“I think the difference [that improved attendance at my child’s school] is that they’re so whānau centred, so community centred. Not everyone’s equipped with what they need to get to school or to do well at school, so bringing it back to how we can help within the family system makes a real change.”

- PARENT

Monitor the impacts of practical supports

It is important to track the impact that a practical intervention has on a students’ attendance and not just assume that attendance improves. The wider evidence on providing practical supports, such as transport, food, or clothing, affirms that they are not instant solutions – they are most effective when part of a wider approach. Teachers and school leaders need to monitor attendance data to see if a shift in attendance patterns has occurred. If there is little or no shift, then it is important to follow up with students, parents and whānau to discuss if additional or different supports.

What does this look like in practice?

Real-life example: Providing practical supports based on school-specific data and evidence

At one small area school, we heard that the neighbourhood buses make a big difference for this school’s families. The provision of transport is especially important for students who live further way, who struggle with routine, or whose parents are unable to provide transport due to work commitments.

“I go on the bus on Fridays… my mum goes to work at the same time”

- STUDENT

We also spoke to some primary schools which have arranged walking buses, which can be especially helpful for working parents and families with siblings at different schools.

In one urban secondary school, uniforms are subsidised by a trust board. Students also support each other by sharing spare uniform items. For example, one student regularly brought extra uniform pieces just in case, to help peers avoid consequences.

As well as uniform support, transport costs are covered for students who live far away, and food is provided daily. Staff and parents note that students who might otherwise struggle to attend are enabled through these practical supports.

Some schools are working with local charities to help with practical supports to help students to attend. Schools told us that the KidsCan programme helps them provide coats and shoes. Some schools also have fundraising events. We heard that lack of warm and protective clothing is a particular challenge for attendance in winter. One small primary school in an urban area told us that food is sourced from local supermarket donations, such as bread rolls nearing expiry, and that these are distributed to families or used to prepare meals for students. The school keeps food in the freezer and staff will make toasties or sandwiches as needed.

“We can always find some sandwich. We can always make someone something.”

- TEACHER

Reflective questions

- How well do we understand the specific, practical barriers to attendance faced by students and families in our school community?

- What processes do we have in place to engage with parents and whānau in a way that invites open conversation about attendance challenges without blame, or shame?

- How do we use attendance data to inform decisions, and to monitor and adapt if those supports don’t lead to improved attendance?

- How can we access resources and support from our community, for example, charities or community groups, to help families overcome practical barriers?

Rewards

Rewarding students for improving or maintaining high attendance can motivate students and positively impact their attitudes towards attendance.

Why does using rewards matter?

Students value rewards because they recognise and affirm their efforts. Rewards also reinforce expectations, as students track their progress against attendance targets in pursuit of these incentives. How rewards work can vary, with some being targeted at individual students and others being more broadly targeted, with things like celebrations, house points, or prizes. Collective rewards strengthen belonging and motivate students to attend so they can contribute to something larger than themselves.

DID YOU KNOW?

When their school uses rewards, students are about one-and-a-half times more likely to think daily attendance is important and one-anda-half times more likely to think school is important for their future. These impacts are more pronounced for primary students than secondary students.

Parents value rewards because they provide tangible recognition of the student’s and family’s efforts to achieve and maintain regular attendance. Parents told us that rewards can provide a meaningful nudge for children who might otherwise struggle with attendance.

Parents think rewards are especially motivating for younger children because they make attendance feel like a fun challenge and align well with how younger children respond to playful, goal-oriented systems. We heard from some secondary parents that their child could be embarrassed receiving individual rewards in front of their peers, but ‘secretly’ likes the recognition. Collective rewards can minimise individual pressure and incentivise students encouraging each other to attend.

DID YOU KNOW?

Parents are nearly twice as likely to view daily attendance as important if the school rewards good attendance. This is more pronounced for primary parents who are more than twice as likely to view daily attendance as important if the school is providing rewards.

How can we use rewards to improve daily attendance?

To improve daily attendance using rewards, school leaders and teachers need to:

1) set realistic and increasing targets

2) reward collectively.

Set realistic and increasing targets

Rewards only have a positive impact on attendance when the targets are realistic and valued by students. If targets are perceived by students and parents as being too far out of their reach, then rewards can have the opposite effect and become de-motivating. Rewards are motivating when they are framed as a fun challenge. This is especially true for younger students who respond to playful, goal-oriented reward systems.

We heard from older students that when the targets are high, they can miss out on attaining them with just a few absences. This makes them feel like the reward system is actually a punishment system. Setting students an individualised target and then gradually increasing this over time works well. This means students can close the gap between their current attendance and the aspirational target. It also stops rewards from becoming de-motivating.

Reward collectively

Collective rewards can further strengthen belonging, motivating students to attend so they can contribute to something larger than themselves. Group-based recognition, like rewarding top attendance by class or year group, is particularly powerful. Students are driven by not wanting to let their peers down, and the team aspect adds a sense of fun. In schools using collective rewards, students described messaging their ‘teammates’ in the morning to check they will attend and said this makes them think twice about staying home.

Using consequences

Consequences need to be used carefully. We found they have a positive impact on parents’ attitudes towards attendance, but a negative impact on students’ attitudes.