Related information

You may also be interested in our other reports relating to English and Maths

Read Online

Introduction

Literacy and numeracy skills are key to future achievement, earning, health, and other outcomes. Developing these foundational skills effectively at primary school sets children up to succeed later. Domestic and international evidence shows that significant improvement is needed to get New Zealand students to the expected levels in reading, writing and maths. They also show the scale of the challenge. Improvements are being made, and encouragingly, they are starting to have an impact.

The Government has made a series of changes to improve achievement across New Zealand, as part of Teaching the Basics Brilliantly. The changes include refreshing the New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (TMoA), and requiring schools to teach one hour a day on each of reading, writing, and maths.

The refreshed English and Te Reo Rangatira (Years 0–6) and mathematics and statistics and pāngarau (Years 0–8) learning areas were published in October 2024. Schools were required to use the refreshed learning areas from Term 1, 2025. While it is still early days, school teachers and leaders have worked hard to change what and how they teach, and are already seeing the impacts of the changes.

Literacy and numeracy skills are key to future achievement, earning, health, and other outcomes. Developing these foundational skills effectively at primary school sets children up to succeed later. Domestic and international evidence shows that significant improvement is needed to get New Zealand students to the expected levels in reading, writing and maths. They also show the scale of the challenge. Improvements are being made, and encouragingly, they are starting to have an impact.

The Government has made a series of changes to improve achievement across New Zealand, as part of Teaching the Basics Brilliantly. The changes include refreshing the New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (TMoA), and requiring schools to teach one hour a day on each of reading, writing, and maths.

The refreshed English and Te Reo Rangatira (Years 0–6) and mathematics and statistics and pāngarau (Years 0–8) learning areas were published in October 2024. Schools were required to use the refreshed learning areas from Term 1, 2025. While it is still early days, school teachers and leaders have worked hard to change what and how they teach, and are already seeing the impacts of the changes.

Are schools using the refreshed English and maths learning areas?

Already, nearly all schools have started using the refreshed curriculum for English and maths, and teachers are changing their practice, using the new content and strategies.

- Nearly all schools report they have started teaching the refreshed English learning area for students in Years 0–6 (98 percent), and the refreshed learning area for maths in Years 0–8 (98 percent).

- All the components of English are taught by more than nine out of ten teachers.

- All the components of maths are taught by more than eight out of ten teachers. Teachers focus on number more than any other part of maths.

- Encouragingly, more than eight in ten teachers report they have changed how they teach English (88 percent) and maths (85 percent). Nearly all teachers (more than 97 percent) use the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

Figure 1: Proportion of teachers who report a change in teaching practice for English and maths

- Teachers and leaders report that a significant change is their increased focus on explicit teaching. Nearly all teachers of Years 0–3 students report using strategies for explicit teaching often.

“I am making sure that I am being more explicit with my instructions. I am also making sure that we are moving through things quicker than I previously would have due to the fact there is a lot to cover in the new curriculums.”

TEACHER

Importantly, teachers across all school types, sizes, and locations are teaching the components of the refreshed curriculum, using the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

- Often, the Education Review Office (ERO) sees differences between schools’ adoption of change. But in this review, ERO found that teachers across socio-economic communities,

different school types, and in both urban and rural areas are all teaching the refreshed curriculum for both English and maths. - Teachers are also using the same strategies of the science of learning across the country.

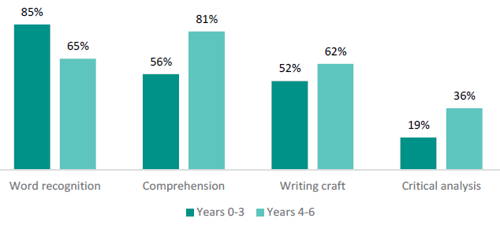

In English, what is taught at different year levels is what is expected – more complex components are taught more for older students. In maths, there is not yet the expected level of shift to more complex components as students get older.

- As expected, more fundamental components of English – like word recognition – are taught more to students in Years 0–3. Older students are taught more comprehension, writing craft, and critical analysis than younger students.

Figure 2: The components of English taught ‘a lot’ across different year groups

“[The biggest change is] the changes in expectations at different year levels. Things we have not taught before at Year 3 the children are now expected to know.”

TEACHER

- In maths, teachers focus on the foundational components across all year levels. For instance, in Years 7–8, three-quarters of teachers (75 percent) teach number ‘a lot’, when we would expect them to teach more of things like algebra, probability and statistics. We found this is due to a combination of factors:

- The change needed in what and how number is taught is greater than the change in other components of maths, so some teachers are prioritising this.

Students need greater support with number. Number has been a relative weakness for New Zealand students, and students are not yet at the level they need to be.

- Teachers are more confident to start with changing their practice in teaching number compared to other aspects of maths.

“The students coming into our school do not have the base of prior knowledge and skills required to competently work in Phase 3 of the new curriculum. Hopefully this improves with time as the curriculum is rolled out across our feeding Primary Schools.”

LEADER

Already, nearly all schools have started using the refreshed curriculum for English and maths, and teachers are changing their practice, using the new content and strategies.

- Nearly all schools report they have started teaching the refreshed English learning area for students in Years 0–6 (98 percent), and the refreshed learning area for maths in Years 0–8 (98 percent).

- All the components of English are taught by more than nine out of ten teachers.

- All the components of maths are taught by more than eight out of ten teachers. Teachers focus on number more than any other part of maths.

- Encouragingly, more than eight in ten teachers report they have changed how they teach English (88 percent) and maths (85 percent). Nearly all teachers (more than 97 percent) use the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

Figure 1: Proportion of teachers who report a change in teaching practice for English and maths

- Teachers and leaders report that a significant change is their increased focus on explicit teaching. Nearly all teachers of Years 0–3 students report using strategies for explicit teaching often.

“I am making sure that I am being more explicit with my instructions. I am also making sure that we are moving through things quicker than I previously would have due to the fact there is a lot to cover in the new curriculums.”

TEACHER

Importantly, teachers across all school types, sizes, and locations are teaching the components of the refreshed curriculum, using the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

- Often, the Education Review Office (ERO) sees differences between schools’ adoption of change. But in this review, ERO found that teachers across socio-economic communities,

different school types, and in both urban and rural areas are all teaching the refreshed curriculum for both English and maths. - Teachers are also using the same strategies of the science of learning across the country.

In English, what is taught at different year levels is what is expected – more complex components are taught more for older students. In maths, there is not yet the expected level of shift to more complex components as students get older.

- As expected, more fundamental components of English – like word recognition – are taught more to students in Years 0–3. Older students are taught more comprehension, writing craft, and critical analysis than younger students.

Figure 2: The components of English taught ‘a lot’ across different year groups

“[The biggest change is] the changes in expectations at different year levels. Things we have not taught before at Year 3 the children are now expected to know.”

TEACHER

- In maths, teachers focus on the foundational components across all year levels. For instance, in Years 7–8, three-quarters of teachers (75 percent) teach number ‘a lot’, when we would expect them to teach more of things like algebra, probability and statistics. We found this is due to a combination of factors:

- The change needed in what and how number is taught is greater than the change in other components of maths, so some teachers are prioritising this.

Students need greater support with number. Number has been a relative weakness for New Zealand students, and students are not yet at the level they need to be.

- Teachers are more confident to start with changing their practice in teaching number compared to other aspects of maths.

“The students coming into our school do not have the base of prior knowledge and skills required to competently work in Phase 3 of the new curriculum. Hopefully this improves with time as the curriculum is rolled out across our feeding Primary Schools.”

LEADER

What are the early impacts?

It is still early days, but there are positive signs that students’ achievement and engagement in both English and maths are improving.

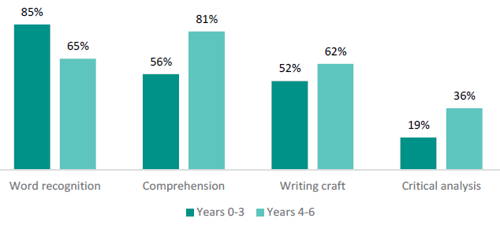

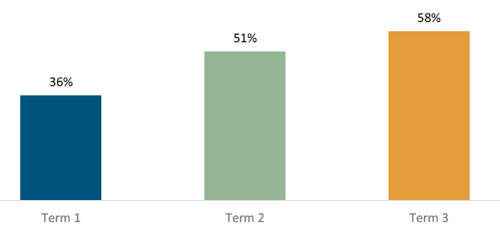

- Phonics checks show a significant improvement in student achievement. In Term 1, 2025, only a third of students (36 percent) achieved at or above the curriculum expectation after 20 weeks of school. In Term 2, over half of students (51 percent) achieved at or above and in Term 3, this rose even further (58 percent). The biggest increase was in the number of students exceeding curriculum expectations, which more than doubled from Term 1 to Term 3 (from 20 percent to 43 percent).

- The data also shows that the curriculum changes are having a positive impact for all

students, with students of different ethnicities and socio-economic groups all making

progress.

Figure 3: Proportion of students at or above the curriculum expectation in phonics checks, after 20 weeks’ instruction

“My reading is getting better… taking time to look at the words. I am reading faster than usual. My fluency has increased.”

STUDENT

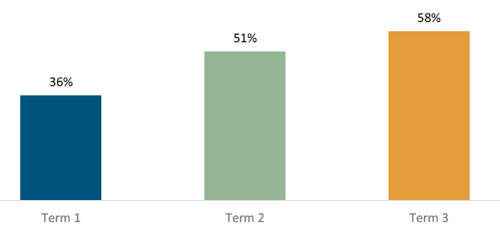

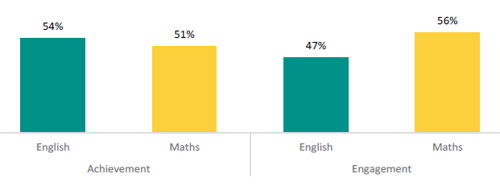

- Encouragingly, half of teachers, across year levels, report improved achievement in English (54 percent) and in maths (51 percent) compared to last year.

- Parents agree. Three-quarters of parents report their child’s progress has improved in English (77 percent) and maths (75 percent) since one hour a day was implemented.

“Structured literacy has been incredibly successful for my child in Year 2. Especially when I compared to my child in Year 4, who didn't follow structured literacy. Much quicker progress, reading fluency, and better spelling.”

PARENT/WHĀNAU

- Students are also more engaged in their learning. Almost half (47 percent) of teachers report improved student engagement in English, and over half (56 percent) of teachers report improved student engagement in maths. Teachers reported that structured literacy approaches have improved attention and behaviour in the classroom.

Figure 4: Percentage of teachers reporting improved student achievement and engagement compared to last year

“Structured literacy has been one of the absolute benefits we’ve had and the most impactful things we’ve had around engagement. We have seen the spinoff of that in other spaces. In particular, with spelling. Some talk of [it being] too structured, ending up with robot kids. But I would absolutely disagree. You can still have fun, spread joy, and love. Make sure you don’t lose the art of teaching.”

TEACHER

- Students also report being engaged. Nine out of ten students report finding their lessons in English and maths interesting.

“It is good [to] see your own progress at the beginning and end of the term…It is more organised this year… Maths is the focus at school this year…There is [a] better whole class explanation this year, more set out and easier to learn.”

STUDENT

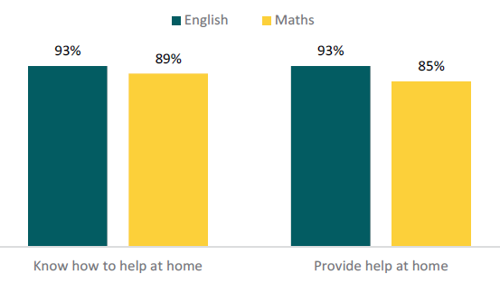

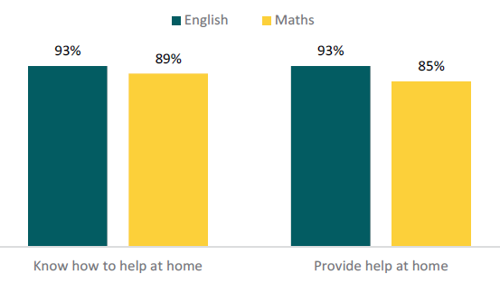

Parents know how to help their child at home, and do. Parents are less confident helping with maths, and would like more guidance.

- Nine in ten parents and whānau members report they know how to help their child at home with reading and writing (93 percent), and maths (89 percent).

- Almost nine in ten parents report helping their child at home with reading, writing (93 percent), and maths (85 percent). For both English and maths, we heard that parents and whānau like to know what content is being covered at school, so they can supplement this learning at home. They would like more guidance to help their child with maths.

Figure 5: Percentage of parents supporting learning at home for English and maths

“It would be good to see the curriculum and how it is taught to have a better understanding of how to support learning from home. I understand the way of teaching has changed over the years, so knowing we are not using outdated techniques would be good.”

PARENT/WHĀNAU

It is still early days, but there are positive signs that students’ achievement and engagement in both English and maths are improving.

- Phonics checks show a significant improvement in student achievement. In Term 1, 2025, only a third of students (36 percent) achieved at or above the curriculum expectation after 20 weeks of school. In Term 2, over half of students (51 percent) achieved at or above and in Term 3, this rose even further (58 percent). The biggest increase was in the number of students exceeding curriculum expectations, which more than doubled from Term 1 to Term 3 (from 20 percent to 43 percent).

- The data also shows that the curriculum changes are having a positive impact for all

students, with students of different ethnicities and socio-economic groups all making

progress.

Figure 3: Proportion of students at or above the curriculum expectation in phonics checks, after 20 weeks’ instruction

“My reading is getting better… taking time to look at the words. I am reading faster than usual. My fluency has increased.”

STUDENT

- Encouragingly, half of teachers, across year levels, report improved achievement in English (54 percent) and in maths (51 percent) compared to last year.

- Parents agree. Three-quarters of parents report their child’s progress has improved in English (77 percent) and maths (75 percent) since one hour a day was implemented.

“Structured literacy has been incredibly successful for my child in Year 2. Especially when I compared to my child in Year 4, who didn't follow structured literacy. Much quicker progress, reading fluency, and better spelling.”

PARENT/WHĀNAU

- Students are also more engaged in their learning. Almost half (47 percent) of teachers report improved student engagement in English, and over half (56 percent) of teachers report improved student engagement in maths. Teachers reported that structured literacy approaches have improved attention and behaviour in the classroom.

Figure 4: Percentage of teachers reporting improved student achievement and engagement compared to last year

“Structured literacy has been one of the absolute benefits we’ve had and the most impactful things we’ve had around engagement. We have seen the spinoff of that in other spaces. In particular, with spelling. Some talk of [it being] too structured, ending up with robot kids. But I would absolutely disagree. You can still have fun, spread joy, and love. Make sure you don’t lose the art of teaching.”

TEACHER

- Students also report being engaged. Nine out of ten students report finding their lessons in English and maths interesting.

“It is good [to] see your own progress at the beginning and end of the term…It is more organised this year… Maths is the focus at school this year…There is [a] better whole class explanation this year, more set out and easier to learn.”

STUDENT

Parents know how to help their child at home, and do. Parents are less confident helping with maths, and would like more guidance.

- Nine in ten parents and whānau members report they know how to help their child at home with reading and writing (93 percent), and maths (89 percent).

- Almost nine in ten parents report helping their child at home with reading, writing (93 percent), and maths (85 percent). For both English and maths, we heard that parents and whānau like to know what content is being covered at school, so they can supplement this learning at home. They would like more guidance to help their child with maths.

Figure 5: Percentage of parents supporting learning at home for English and maths

“It would be good to see the curriculum and how it is taught to have a better understanding of how to support learning from home. I understand the way of teaching has changed over the years, so knowing we are not using outdated techniques would be good.”

PARENT/WHĀNAU

How are schools doing it?

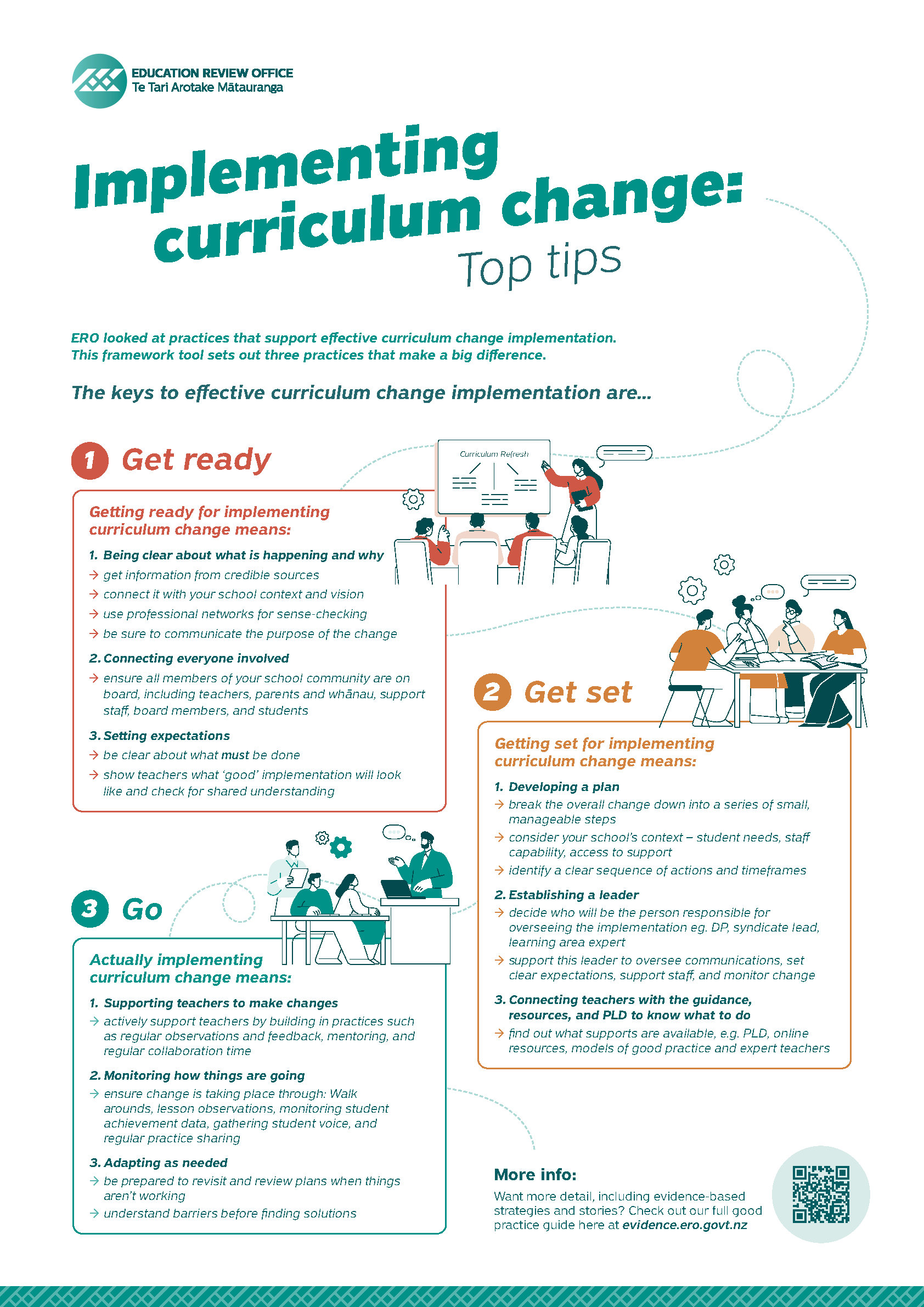

ERO found that schools are achieving this change through:

1) Increasing the time spent on reading, writing, and maths.

2) Planning, setting expectations, and providing support

3) Accessing impactful resources and support.

1) Increasing the time

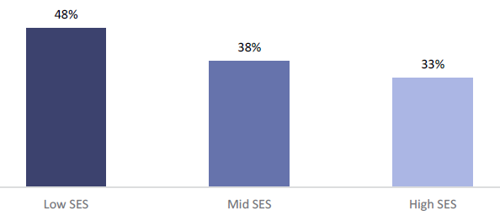

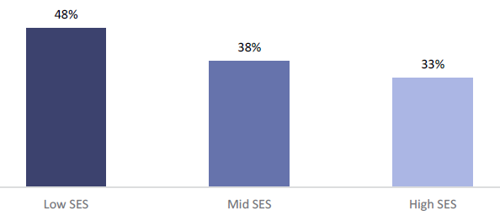

Encouragingly, around one third of teachers report they have increased the time spent on reading, writing, and maths, since the requirement to do an hour a day. Even more schools in lower socio-economic communities have increased the time spent on these subjects.

- Around a third of teachers report an increase in time spent teaching reading, writing, and maths. For many teachers, they report that this is an increase in time spent on explicit teaching.

- Almost half of teachers in schools in low socio-economic communities have increased the time spent on maths, compared to just under two in five teachers in the middle of the socio-economic scale and a third in schools serving high socio-economic communities. This is especially important, as students in schools in low socio-economic communities tend to have lower achievement.

Figure 6: Percentage of teachers who report an increase in the time spent on maths since 2023 across socio-economic status

- Importantly, around two-thirds of teachers report they do an hour a day every day for reading (60 percent) and maths (67 percent).

“The school has one more hour focusing on reading and writing, focusing on the area of my child’s weakness and trying to improve it. I have seen so many improvements in my child.”

PARENT/ WHĀNAU

2) Planning, setting expectations, and providing support

Most schools have expectations and plans in place. More school leaders are supporting teachers to make the changes to maths, than to English.

- Nine out of ten leaders report they know what they need to do to implement the new curriculum for English (89 percent) and maths (95 percent). Most schools have a plan, and someone to lead the delivery of the plan.

- School leaders told us that they know what they need to do to implement the curriculum because of the information they have received from different sources, such as the guidance documents, communications from the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), and through peer networks.

- Nearly all school leaders have set expectations for teachers to use the new curriculum (85 percent for English, 95 percent for maths). Leaders told us that, while they are balancing competing demands on teachers’ time, they are clear with teachers that they are expected to be delivering the new curriculum.

- Leaders are supporting teachers more for maths, as many were already using some form of structured literacy approach, so the change for maths was greater.

“We started planning last year, we started using the training and resources with the cohorts this year… We wanted everyone across the school in each year group to have strong knowledge around the science of reading. We have decided to wait till Term 3 to roll out the maths once all the teachers have had maths professional development.”

LEADER

3) Impactful resources and support

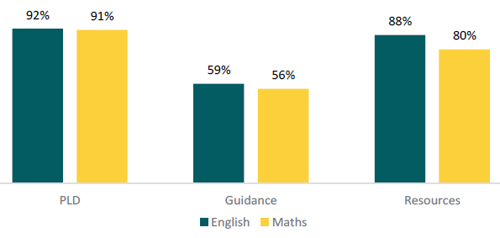

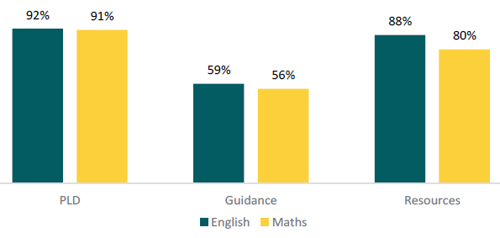

Guidance and resources for English and maths are making a big impact for teachers who have accessed it.

- Over eight in ten teachers (82 percent) have accessed professional learning and development (PLD) on structured literacy approaches, and over three-quarters of teachers

(76 percent) have accessed the Ministry’s maths PLD. More than nine out of ten teachers have accessed professional development for English (92 percent) or maths (91 percent) more

generally. Leaders and teachers told us that they find the clarity and practicality of the PLD particularly useful. - Teachers who have accessed guidance for English are 3.5 times more likely to have changed their practice. Teachers who accessed any resources for maths were nearly 4 times more likely to report changing their teaching practice.

Figure 7: Proportion of teachers who access any PLD, guidance, and resources for English and maths

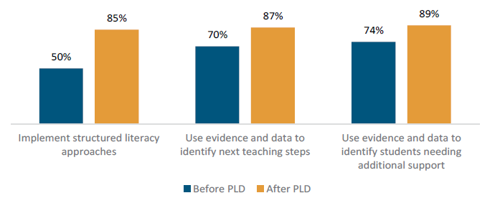

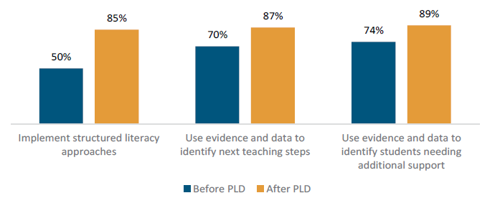

Professional development on structured literacy approaches improves teachers’ knowledge and confidence.

- Teachers who participated in the Ministry’s professional development on structured literacy approaches grew their knowledge of the approaches. Before the development, teachers had 60 percent correct answers on knowledge questions, and this increased to 78 percent following the development. Teachers also reported improved confidence to:

- implement structured literacy approaches (a shift from 50 percent before the professional development to 85 percent after)

- use evidence and data to identify next teaching steps (70 percent to 87 percent)

- use evidence and data to identify students needing additional support (74 percent to 89 percent).

Figure 8: Percentage of teachers who report they are confident to use elements of structured literacy approaches before and after professional development

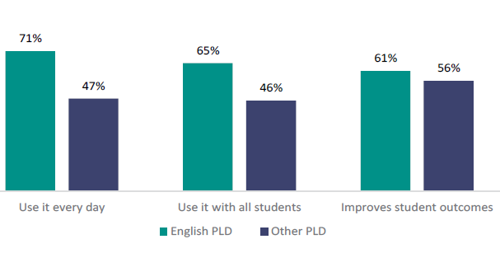

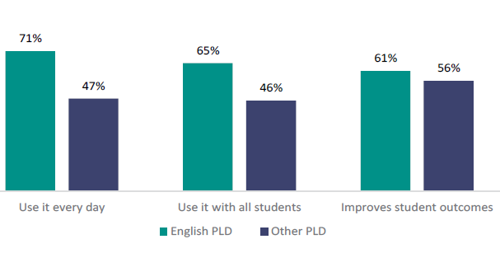

The professional development to support teachers with the English and maths learning areas is useful, and more useful than other professional development.

- Of those who accessed the PLD for supporting them to implement the refreshed English maths learning areas, nearly all teachers report that it was useful. For example;

- 96 percent report professional development on structured literacy approaches is useful

- 91 percent report professional development on maths is useful - This compares to eight of ten primary school teachers who report that PLD is useful overall.

- Teachers whose most recent external professional development was on English report they use what they have learnt every day (71 percent), use it with all students (65 percent) and see improvements in student outcomes (61 percent).

Figure 9: Primary school teachers who report their most recent external professional development was on English, compared to teachers receiving other professional development

“[The] structured literacy programme explicitly taught us how to use the resources, how to go through the entire book and the speed words, fun ways of teaching. [It got us] understanding why it works, how it goes through all the letters, and being able to read independently and confidently.”

BEGINNING TEACHER

ERO found that schools are achieving this change through:

1) Increasing the time spent on reading, writing, and maths.

2) Planning, setting expectations, and providing support

3) Accessing impactful resources and support.

1) Increasing the time

Encouragingly, around one third of teachers report they have increased the time spent on reading, writing, and maths, since the requirement to do an hour a day. Even more schools in lower socio-economic communities have increased the time spent on these subjects.

- Around a third of teachers report an increase in time spent teaching reading, writing, and maths. For many teachers, they report that this is an increase in time spent on explicit teaching.

- Almost half of teachers in schools in low socio-economic communities have increased the time spent on maths, compared to just under two in five teachers in the middle of the socio-economic scale and a third in schools serving high socio-economic communities. This is especially important, as students in schools in low socio-economic communities tend to have lower achievement.

Figure 6: Percentage of teachers who report an increase in the time spent on maths since 2023 across socio-economic status

- Importantly, around two-thirds of teachers report they do an hour a day every day for reading (60 percent) and maths (67 percent).

“The school has one more hour focusing on reading and writing, focusing on the area of my child’s weakness and trying to improve it. I have seen so many improvements in my child.”

PARENT/ WHĀNAU

2) Planning, setting expectations, and providing support

Most schools have expectations and plans in place. More school leaders are supporting teachers to make the changes to maths, than to English.

- Nine out of ten leaders report they know what they need to do to implement the new curriculum for English (89 percent) and maths (95 percent). Most schools have a plan, and someone to lead the delivery of the plan.

- School leaders told us that they know what they need to do to implement the curriculum because of the information they have received from different sources, such as the guidance documents, communications from the Ministry of Education (the Ministry), and through peer networks.

- Nearly all school leaders have set expectations for teachers to use the new curriculum (85 percent for English, 95 percent for maths). Leaders told us that, while they are balancing competing demands on teachers’ time, they are clear with teachers that they are expected to be delivering the new curriculum.

- Leaders are supporting teachers more for maths, as many were already using some form of structured literacy approach, so the change for maths was greater.

“We started planning last year, we started using the training and resources with the cohorts this year… We wanted everyone across the school in each year group to have strong knowledge around the science of reading. We have decided to wait till Term 3 to roll out the maths once all the teachers have had maths professional development.”

LEADER

3) Impactful resources and support

Guidance and resources for English and maths are making a big impact for teachers who have accessed it.

- Over eight in ten teachers (82 percent) have accessed professional learning and development (PLD) on structured literacy approaches, and over three-quarters of teachers

(76 percent) have accessed the Ministry’s maths PLD. More than nine out of ten teachers have accessed professional development for English (92 percent) or maths (91 percent) more

generally. Leaders and teachers told us that they find the clarity and practicality of the PLD particularly useful. - Teachers who have accessed guidance for English are 3.5 times more likely to have changed their practice. Teachers who accessed any resources for maths were nearly 4 times more likely to report changing their teaching practice.

Figure 7: Proportion of teachers who access any PLD, guidance, and resources for English and maths

Professional development on structured literacy approaches improves teachers’ knowledge and confidence.

- Teachers who participated in the Ministry’s professional development on structured literacy approaches grew their knowledge of the approaches. Before the development, teachers had 60 percent correct answers on knowledge questions, and this increased to 78 percent following the development. Teachers also reported improved confidence to:

- implement structured literacy approaches (a shift from 50 percent before the professional development to 85 percent after)

- use evidence and data to identify next teaching steps (70 percent to 87 percent)

- use evidence and data to identify students needing additional support (74 percent to 89 percent).

Figure 8: Percentage of teachers who report they are confident to use elements of structured literacy approaches before and after professional development

The professional development to support teachers with the English and maths learning areas is useful, and more useful than other professional development.

- Of those who accessed the PLD for supporting them to implement the refreshed English maths learning areas, nearly all teachers report that it was useful. For example;

- 96 percent report professional development on structured literacy approaches is useful

- 91 percent report professional development on maths is useful - This compares to eight of ten primary school teachers who report that PLD is useful overall.

- Teachers whose most recent external professional development was on English report they use what they have learnt every day (71 percent), use it with all students (65 percent) and see improvements in student outcomes (61 percent).

Figure 9: Primary school teachers who report their most recent external professional development was on English, compared to teachers receiving other professional development

“[The] structured literacy programme explicitly taught us how to use the resources, how to go through the entire book and the speed words, fun ways of teaching. [It got us] understanding why it works, how it goes through all the letters, and being able to read independently and confidently.”

BEGINNING TEACHER

Where do schools need more support?

Overall, teachers and leaders are embracing the changes. There are three areas, however, where teachers need more support. These are:

1) To teach maths.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools.

3) To enable and extend students’ learning.

1) To teach maths

Teachers report needing more support to teach maths, and to fill in gaps in students’ learning.

- More than eight out of ten teachers teach all components of maths.

- Concerningly, so far, teachers focus on number, and all other components are taught less. The focus on teaching number does not shift, even in more senior levels.

- This focus on number is not new. Teachers also focused on number in the previous maths learning area, where nearly all Year 5 students had been taught elements of number, and significantly fewer had been taught other topics.

- Number has been an area of challenge for students over time, and teachers and leaders report the revised curriculum expects even more from students than the previous.

- Some teachers are less confident to teach complex maths content, and are more comfortable teaching number, and are focusing first on adapting their practice in this area.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools

Small schools and rural schools face bigger challenges in implementing the change. For example, they are less likely to have someone leading implementation, or to have a plan for implementing the changes.

- Only eight in ten small schools have a plan for implementing the changes for maths (84 percent), or someone leading delivery on the plan (78 percent). This is even lower for implementing English, where only seven in ten (69 percent) of small schools have a plan.

“In a small school with only four teachers, and two are beginning teachers and a teaching Principal, there is only one senior teacher available to lead the curriculum implementation, while teaching full-time and mentoring the other teachers. She hasn’t had the time to look through all the documents; we are running behind on maths."

PRINCIPAL

3) To enable and extend students’ learning

Some teachers need further support to know how to enable students to reach the curriculum level for their year, and extend students’ learning.

- It is still early days for the curriculum, and teachers and leaders are not always sure what the core components of structured literacy or maths are, and where there is flexibility.

- To manage this, leaders told us they support teachers to contextualise what they learn in PLD in their classroom. They put effort into agreeing on common practices and ensuring that teachers have consistent messages, especially if teachers shift between schools.

- Some teachers report being unsure about adapting their teaching to meet students’ needs, in particular, to support or extend students in multi-year classrooms, or when there is a wide range of ability within a year group.

- They are also uncertain about adapting for neurodivergent or disabled learners. They want further guidance on when and how to escalate support for students who need additional help and more resources to enable this.

“[There are challenges in] how to structure year group lessons across multi-level classrooms, ensuring that students have their ‘gaps’ filled before building age-appropriate knowledge and skills, how to keep a track of where students are at in each year group and track assessments.”

LEADER

It is earlier days for kura and rumaki. While they generally support the changes, leaders and teachers report challenges accessing the supports and using them in their specific settings.

While positive about the support they have received, leaders and teachers in kura and rumaki report some significant barriers to accessing the PLD, guidance, and resources they need to implement the changes.

Leaders shared that PLD, guidance, and resources for Māori-medium provision do not necessarily reflect the breadth of the settings students are learning in. This means there is little change in what and how students are being taught. Teachers in rumaki told us they find it especially challenging. They often translate and adapt English-medium PLD, guidance, and resources for their classes, as they have greater access to these.

Some settings are managing to make it work. Experienced leaders told us that where changes have begun, it is because of the capability and experience of both their leaders

and teachers.

“Once staff got started we actually enjoyed it.”

LEADER/TUMUAKI

Overall, teachers and leaders are embracing the changes. There are three areas, however, where teachers need more support. These are:

1) To teach maths.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools.

3) To enable and extend students’ learning.

1) To teach maths

Teachers report needing more support to teach maths, and to fill in gaps in students’ learning.

- More than eight out of ten teachers teach all components of maths.

- Concerningly, so far, teachers focus on number, and all other components are taught less. The focus on teaching number does not shift, even in more senior levels.

- This focus on number is not new. Teachers also focused on number in the previous maths learning area, where nearly all Year 5 students had been taught elements of number, and significantly fewer had been taught other topics.

- Number has been an area of challenge for students over time, and teachers and leaders report the revised curriculum expects even more from students than the previous.

- Some teachers are less confident to teach complex maths content, and are more comfortable teaching number, and are focusing first on adapting their practice in this area.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools

Small schools and rural schools face bigger challenges in implementing the change. For example, they are less likely to have someone leading implementation, or to have a plan for implementing the changes.

- Only eight in ten small schools have a plan for implementing the changes for maths (84 percent), or someone leading delivery on the plan (78 percent). This is even lower for implementing English, where only seven in ten (69 percent) of small schools have a plan.

“In a small school with only four teachers, and two are beginning teachers and a teaching Principal, there is only one senior teacher available to lead the curriculum implementation, while teaching full-time and mentoring the other teachers. She hasn’t had the time to look through all the documents; we are running behind on maths."

PRINCIPAL

3) To enable and extend students’ learning

Some teachers need further support to know how to enable students to reach the curriculum level for their year, and extend students’ learning.

- It is still early days for the curriculum, and teachers and leaders are not always sure what the core components of structured literacy or maths are, and where there is flexibility.

- To manage this, leaders told us they support teachers to contextualise what they learn in PLD in their classroom. They put effort into agreeing on common practices and ensuring that teachers have consistent messages, especially if teachers shift between schools.

- Some teachers report being unsure about adapting their teaching to meet students’ needs, in particular, to support or extend students in multi-year classrooms, or when there is a wide range of ability within a year group.

- They are also uncertain about adapting for neurodivergent or disabled learners. They want further guidance on when and how to escalate support for students who need additional help and more resources to enable this.

“[There are challenges in] how to structure year group lessons across multi-level classrooms, ensuring that students have their ‘gaps’ filled before building age-appropriate knowledge and skills, how to keep a track of where students are at in each year group and track assessments.”

LEADER

It is earlier days for kura and rumaki. While they generally support the changes, leaders and teachers report challenges accessing the supports and using them in their specific settings.

While positive about the support they have received, leaders and teachers in kura and rumaki report some significant barriers to accessing the PLD, guidance, and resources they need to implement the changes.

Leaders shared that PLD, guidance, and resources for Māori-medium provision do not necessarily reflect the breadth of the settings students are learning in. This means there is little change in what and how students are being taught. Teachers in rumaki told us they find it especially challenging. They often translate and adapt English-medium PLD, guidance, and resources for their classes, as they have greater access to these.

Some settings are managing to make it work. Experienced leaders told us that where changes have begun, it is because of the capability and experience of both their leaders

and teachers.

“Once staff got started we actually enjoyed it.”

LEADER/TUMUAKI

What key lessons have we learned about effective curriculum change?

By reflecting on what was particularly successful through implementing the English and maths learning area changes, and where there have been particular challenges, we identified three key lessons to inform future curriculum change.

1) A well-designed curriculum change package can be highly impactful in igniting change across all schools.

- A clear purpose is key to successful curriculum change. This needs to be communicated effectively so that the purpose is understood by teachers, leaders, families, and the wider community.

- Signalling and sequencing of change works. A curriculum change package works best when it is supported by evidence and tailored for New Zealand’s students. It needs to be supported by a well-planned sequence of changes, and the right support needs to be available at the

right time. - Strong leadership can drive change in schools. Schools make change best when supported by a leader who is responsible for driving the curriculum change and setting clear expectations. Good leaders reinforce and embed changes through supports and resources, and set aside time for teachers to embed learning.

2) Building teacher capability is essential for successful curriculum change, which makes a difference for students.

- High-quality professional development can build capability and motivation. Professional development can change practice in schools when it builds knowledge, motivates teachers to use what they learn, develops teaching techniques, and provides structures and strategies to embed good practice.

- Providing targeted support to teachers who most need it can ensure change happens in all classrooms. This includes building foundational capability where teachers lack confidence or knowledge.

3) Tailored approaches for schools with greater challenges are key to generating change where it is needed most.

- With support, it is possible to achieve the biggest shift in schools facing the most challenges. These supports can work well when provided through a national change package.

- Parent engagement can support the implementation of change. Tailored communication to communities from trusted sources, such as teachers and school leaders, can be the most successful.

By reflecting on what was particularly successful through implementing the English and maths learning area changes, and where there have been particular challenges, we identified three key lessons to inform future curriculum change.

1) A well-designed curriculum change package can be highly impactful in igniting change across all schools.

- A clear purpose is key to successful curriculum change. This needs to be communicated effectively so that the purpose is understood by teachers, leaders, families, and the wider community.

- Signalling and sequencing of change works. A curriculum change package works best when it is supported by evidence and tailored for New Zealand’s students. It needs to be supported by a well-planned sequence of changes, and the right support needs to be available at the

right time. - Strong leadership can drive change in schools. Schools make change best when supported by a leader who is responsible for driving the curriculum change and setting clear expectations. Good leaders reinforce and embed changes through supports and resources, and set aside time for teachers to embed learning.

2) Building teacher capability is essential for successful curriculum change, which makes a difference for students.

- High-quality professional development can build capability and motivation. Professional development can change practice in schools when it builds knowledge, motivates teachers to use what they learn, develops teaching techniques, and provides structures and strategies to embed good practice.

- Providing targeted support to teachers who most need it can ensure change happens in all classrooms. This includes building foundational capability where teachers lack confidence or knowledge.

3) Tailored approaches for schools with greater challenges are key to generating change where it is needed most.

- With support, it is possible to achieve the biggest shift in schools facing the most challenges. These supports can work well when provided through a national change package.

- Parent engagement can support the implementation of change. Tailored communication to communities from trusted sources, such as teachers and school leaders, can be the most successful.

Recommendations

ERO used these findings and key lessons learned to make 12 recommendations across six areas. One term in, there is already widespread adoption of the changes, and teachers are changing their practice across the country, we can build on this success.

Area 1: Continue doing what works

To help maintain focus on the things that work, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1 - The Ministry of Education continue to clearly communicate the purpose for the changes.

Recommendation 2 - The Ministry continue to provide tightly defined, centrally commissioned, high-quality PLD.

Recommendation 3 -The Ministry continue to provide a package of support for school leaders and teachers, so they know what to do and have the skills and resources to do it.

Recommendation 4 -The Ministry continue to focus support for schools in low socio-economic communities.

Area 2: Strengthen teachers’ capability in maths

To make sure teachers have the capability to improve student achievement in maths, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 5 -The Ministry develop and implement a package of supports for leaders and teachers to raise their capability to teach more complex maths.

Area 3: Support teachers to enable and extend students appropriately

To strengthen teachers’ capability to meet the needs of all students, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6 - The Ministry provide a package of support – including PLD, guidance, and resources – to help leaders and teachers enable students to catch up or extend their learning.

Recommendation 7 - The Ministry ensure adequate and appropriate specialist supports are available for students who need it, and teachers have guidance to know when it is needed.

Recommendation 8 - Initial teacher education should have a strong focus on the teaching practices needed to enable and extend students’ learning.

Area 4: Ensure support reaches the schools and teachers that most need it

To better support small and isolated schools, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 9 - The Ministry develop a new model for enabling small or isolated schools to access the PLD and the support they need to implement curriculum changes.

Area 5: Strengthen and prioritise resources for implementing TMoA

To help ensure Kura and rūmaki have the knowledge, skills and resources to implement TMoA, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 10 - The Ministry work to increase access and uptake of resources and support for embedding TMoA changes, especially focusing on tailored supports for pāngarau.

Area 6: Embed and sustain the changes

To make sure progress continues, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 11 - The Ministry provide guidance to parents, to help them more effectively support their child’s maths learning at home.

Recommendation 12 - ERO and the Ministry continue to monitor schools’ implementation of the curriculum changes, to identify and take any action needed to ensure schools can embed and sustain the changes to practice.

ERO used these findings and key lessons learned to make 12 recommendations across six areas. One term in, there is already widespread adoption of the changes, and teachers are changing their practice across the country, we can build on this success.

Area 1: Continue doing what works

To help maintain focus on the things that work, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 1 - The Ministry of Education continue to clearly communicate the purpose for the changes.

Recommendation 2 - The Ministry continue to provide tightly defined, centrally commissioned, high-quality PLD.

Recommendation 3 -The Ministry continue to provide a package of support for school leaders and teachers, so they know what to do and have the skills and resources to do it.

Recommendation 4 -The Ministry continue to focus support for schools in low socio-economic communities.

Area 2: Strengthen teachers’ capability in maths

To make sure teachers have the capability to improve student achievement in maths, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 5 -The Ministry develop and implement a package of supports for leaders and teachers to raise their capability to teach more complex maths.

Area 3: Support teachers to enable and extend students appropriately

To strengthen teachers’ capability to meet the needs of all students, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 6 - The Ministry provide a package of support – including PLD, guidance, and resources – to help leaders and teachers enable students to catch up or extend their learning.

Recommendation 7 - The Ministry ensure adequate and appropriate specialist supports are available for students who need it, and teachers have guidance to know when it is needed.

Recommendation 8 - Initial teacher education should have a strong focus on the teaching practices needed to enable and extend students’ learning.

Area 4: Ensure support reaches the schools and teachers that most need it

To better support small and isolated schools, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 9 - The Ministry develop a new model for enabling small or isolated schools to access the PLD and the support they need to implement curriculum changes.

Area 5: Strengthen and prioritise resources for implementing TMoA

To help ensure Kura and rūmaki have the knowledge, skills and resources to implement TMoA, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 10 - The Ministry work to increase access and uptake of resources and support for embedding TMoA changes, especially focusing on tailored supports for pāngarau.

Area 6: Embed and sustain the changes

To make sure progress continues, ERO recommends:

Recommendation 11 - The Ministry provide guidance to parents, to help them more effectively support their child’s maths learning at home.

Recommendation 12 - ERO and the Ministry continue to monitor schools’ implementation of the curriculum changes, to identify and take any action needed to ensure schools can embed and sustain the changes to practice.

Want to know more?

To learn more about how teachers and leaders are using the refreshed English and maths learning areas, and what is helping them make the change, check out our full national review report and short good practice guide for school leaders.

These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website: www.evidence.ero.govt.nz

To learn more about how teachers and leaders are using the refreshed English and maths learning areas, and what is helping them make the change, check out our full national review report and short good practice guide for school leaders.

These can be downloaded for free from ERO’s Evidence and Insights website: www.evidence.ero.govt.nz

ERO’s suite National Review suite of products

|

Title A new chapter:

School leaders’ good practice: Implementing |

What's it about? The review report shares what ERO found out about how teachers are using refreshed English and maths learning areas.

The good practice guide sets out |

Whos is it for? School leaders, teachers, board

School leader

|

|

Title A new chapter:

School leaders’ good practice: Implementing |

What's it about? The review report shares what ERO found out about how teachers are using refreshed English and maths learning areas.

The good practice guide sets out |

Whos is it for? School leaders, teachers, board

School leader

|

What ERO did

Data collected for this report includes:

Over 6300 survey responses from:

- 1031 responses from school leaders

- 1122 responses from teachers of students in Years 0-8

- 2524 responses from parents and whānau of students in Years 0-8

- 1632 responses from students in Years 4–8

- 38 Kura ā Iwi and Kura Motuhake

- 32 rumaki / reo rua units

More than 500 interviews, including:

- 113 interviews with school leaders

- 123 interviews with teachers

- 35 interviews with parents and whānau

- 232 interviews with students

- Leaders and teachers at three kura and five rumaki

Site visits to:

- 36 schools with students in Years 0–8

Observations of:

- 54 English or maths lessons in Years 0–8 classes

ERO Evaluation Partner judgments:

- 432 schools

Data from:

- 5728 termly Ministry check-in survey responses

- Administrative data from the Ministry, including phonics checks

assessments and pre- and post-testing of students and teachers - An in-depth review of local and international literature

- Ministry of Education guidance and information

Data collected for this report includes:

Over 6300 survey responses from:

- 1031 responses from school leaders

- 1122 responses from teachers of students in Years 0-8

- 2524 responses from parents and whānau of students in Years 0-8

- 1632 responses from students in Years 4–8

- 38 Kura ā Iwi and Kura Motuhake

- 32 rumaki / reo rua units

More than 500 interviews, including:

- 113 interviews with school leaders

- 123 interviews with teachers

- 35 interviews with parents and whānau

- 232 interviews with students

- Leaders and teachers at three kura and five rumaki

Site visits to:

- 36 schools with students in Years 0–8

Observations of:

- 54 English or maths lessons in Years 0–8 classes

ERO Evaluation Partner judgments:

- 432 schools

Data from:

- 5728 termly Ministry check-in survey responses

- Administrative data from the Ministry, including phonics checks

assessments and pre- and post-testing of students and teachers - An in-depth review of local and international literature

- Ministry of Education guidance and information