Literacy and numeracy skills are key to future achievement, earnings,

health, and other outcomes. Developing these foundational skills

effectively at primary school sets children up to succeed later. Domestic and international evidence shows that significant improvement is needed to get New Zealand students to the expected levels in reading, writing, and maths. They also show the scale of the challenge. Improvements are being made, and encouragingly, they are starting to have an impact.

The Government has made a series of changes to improve achievement across New Zealand, as part of Teaching the Basics Brilliantly. The changes include refreshing the New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (TMoA), and requiring schools to teach one hour a day on each of reading, writing and maths.

The refreshed English and Te Reo Rangatira (Years 0–6) and maths

and pāngarau (Years 0–8) learning areas were published in October

2024. Schools were required to use the refreshed learning areas from

Term 1, 2025. While it is still early days, school teachers and leaders

have worked hard to change what and how they teach and are

already seeing the impacts of the changes.

Are schools using the refreshed English and maths

learning areas?

Already, nearly all schools have started using the refreshed curriculum for English and maths, and teachers are changing their practice, using the new content and strategies.

- Nearly all schools report they have started teaching the refreshed English learning area for students in Years 0–6 (98 percent), and the refreshed curriculum for maths in Years 0–8 (98 percent).

- All the components of English are taught by more than nine out of ten teachers.

- All the components of maths are taught by more than eight out of ten teachers.Teachers focus on number more than any other part of maths.

- More than eight in ten teachers report they have changed how they teach English (88 percent) and maths (85 percent). Nearly all teachers (more than 97 percent) use the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

- Teachers and leaders report a significant change is their increased focus on explicit teaching. Nearly all teachers of Years 0–3 students report using strategies for explicit teaching often.

Importantly, teachers across all school types, sizes, and locations are teaching all the components of the refreshed curriculum, using the range of evidence-backed teaching strategies that are part of the curriculum changes.

- Often, the Education Review Office (ERO) sees differences between schools’ adoption of change. But in this review, ERO found that teachers across socioeconomic communities, different school types and in both urban and rural areas are all teaching the refreshed curriculum for both English and maths.

- Teachers are also using the same strategies of the science of learning across the country.

In English, what is taught at different year levels is what is expected – more complex components are taught more for older students. In maths, there is not yet the expected level of shift to more complex components as students get older.

- As expected, more fundamental components of English like word recognition are taught more for students in Years 0–3. Older students are taught more comprehension, writing craft, and critical analysis than younger students.

- In maths, teachers focus on the foundational components across all year levels. For instance, in Years 7–8, three-quarters of teachers (75 percent) teach number ‘a lot’, when we would expect them to teach more of things like algebra, probability and statistics. We found this is due to a combination of factors:

- The change in what and how number is taught is greater than the change in other components of maths, so some teachers are prioritising this.

- Students need greater support with number. Number has been a relative weakness for New Zealand students, and students are not yet at the level they need to be.

- Teachers are more confident to start with changing their practice in teaching number compared to other aspects of maths.

What are the early impacts?

It is still early days, but there are positive signs that students’ achievement and engagement in English and maths is improving.

- Phonics checks show a significant improvement in student achievement. In Term 1, 2025, only a third of students (36 percent) achieved at or above the curriculum expectation after 20 weeks of school. In Term 2, over half of students (51 percent)

achieved at or above, and in Term 3, this number rose even further (58 percent). The biggest increase was in the proportion of students exceeding curriculum expectations, which more than doubled from Term 1 to Term 3 (from 20 percent to 43 percent).

- Half of teachers, across year levels, report improved achievement in English(54 percent) and in maths (51 percent) compared to last year.

- Parents also agree. Just over three quarters of parents report their child’s progress has improved in English (77 percent) and maths (75 percent) since one hour a day was implemented.

- Students are also more engaged in their learning. Almost half (47 percent) of teachers report improved student engagement in English, and just under three in five (56 percent) teachers report improved student engagement in maths. Teachers told us that structured literacy approaches have improved attention and behaviour in the classroom.

- Nine out of ten students report finding their lessons in English and maths interesting, showing high levels of engagement.

Most parents know how to help their child at home, and do. Parents are less confident helping with maths, and would like more guidance.

- Nine in ten parents and whānau members report they know how to help their child at home with reading and writing (93 percent) and maths (89 percent).

- Almost nine in ten parents report helping their child at home with reading, writing (93 percent) and maths (85 percent). For both English and maths, we heard that parents and whānau like to know what content is being covered at school, so they can supplement this learning at home. They would like more guidance to help their child with maths.

How are schools doing it?

ERO found that schools are achieving this change through:

1) Increasing the time spent on reading, writing and maths.

2) Planning, setting expectations and providing support.

3) Accessing impactful resources and support.

1) Increasing the time

Encouragingly, around one third of teachers report they have increased the time spent on reading, writing and maths, since the requirement to do an hour a day. Even more schools in lower socio-economic communities have increased the time spent.

- Around a third of teachers report an increase in time spent teaching reading, writing, and maths. For many teachers, they report that this is an increase in time spent on explicit teaching.

- Almost half of teachers in low socio-economic schools have increased the time spent on maths, compared to just under two in five teachers in the middle of the socio-economic scale and a third of schools serving high socio-economic

communities.

- Importantly, around two-thirds of teachers report they do an hour a day every day for reading (60 percent) and maths (67 percent).

2) Planning, setting expectations, and providing support

Most schools have expectations and plans in place. More school leaders are supporting teachers to make the changes to maths, than to English.

- Nine out of ten leaders (90 percent) report they know what they need to do to implement the new curriculum for English (89 percent) and maths (95 percent). Most schools have a plan, and someone to lead delivery of the plan.

- School leaders told us that they know what they need to do to implement the curriculum because of the information they have received from different sources, such as the guidance documents, communications from the Ministry of Education, and through peer networks.

- Nearly all school leaders have set expectations for teachers to use the new learning areas (85 percent for English, 95 percent for maths). Leaders told us that, while they are balancing competing demands on teachers’ time, they are clear with teachers that they are expected to be delivering the new curriculum.

- Leaders are supporting teachers more for maths, as many were already using some form of structured literacy approach, so the change for maths was greater.

3) Impactful resources and support

Guidance and resources for English and maths are making a big impact for teachers who have accessed it.

- Over eight in ten teachers (82 percent) have accessed PLD on structured literacy approaches and over three quarters of teachers (76 percent) have accessed the Ministry’s maths PLD. More than nine out of ten teachers have accessed professional development for English (92 percent) or maths (91 percent) more generally. Leaders and teachers told us that they find the clarity and practicality of the PLD particularly useful.

- Teachers who have accessed guidance for English are 3.5 times more likely to have changed their practice. Teachers who accessed any resources for maths were nearly 4 times more likely to report changing their teaching practice.

Professional development on structured literacy approaches improves teachers’ knowledge and confidence.

Teachers who participated in the Ministry’s professional development on structured literacy approaches grew their knowledge of the approaches. Before the development, teachers had 60 percent correct answers on knowledge questions, and this increased to 78 percent following the development. Teachers also reported improved confidence to:

- implement structured literacy approaches (a shift from 50 percent before the professional development to 85 percent after)

- use evidence and data to identify next teaching steps (70 percent to 87 percent)

- use evidence and data to identify students needing additional support (74 percent to 89 percent).

The PLD to support teachers with the English and maths learning areas is useful, and more useful than other PLD.

- Nearly all teachers report PLD for supporting them to implement the refreshed English and maths learning areas is useful:

- 96 percent report PLD on structured literacy approaches is useful.

- 91 percent report PLD on maths is useful.

- This compares to eight of ten teachers who report PLD is useful overall.

- Teachers whose most recent external PLD was on English report they use what they have learnt every day (71 percent), use it with all students (65 percent) and see improvements in student outcomes (61 percent).

Where do schools need more support?

Overall, teachers and leaders are embracing the changes. There are three areas, however, where teachers need more support:

1) To teach maths.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools.

3) To enable and extend students’ learning.

1) Teaching maths

Teachers report needing more support to teach maths, and to fill in gaps in students’ learning.

- More than eight out of ten teachers teach all components of maths.

- Concerningly, so far, teachers focus on number, and all other components are taught less. The focus on teaching number does not shift, even in more senior levels.

- This focus on number is not new. Teachers also focused on number in the previous maths learning area, where nearly all Year 5 students had been taught elements of number, and significantly fewer had been taught other topics.

- Number has been an area of challenge for Year 5 students over time, and teachers and leaders report the revised curriculum expects even more from students than the previous.

- Some teachers are less confident to teach complex maths content, and are more comfortable teaching number.

2) To help teachers in small and rural schools

Small schools and rural schools face bigger challenges in implementing the change. For example, they are less likely to have someone leading implementation, or to have a plan for implementing the changes.

- Only eight in ten small schools have a plan for implementing the changes for maths (84 percent), or someone leading delivery on the plan (78 percent). This is even lower for implementing English, where only seven in ten (69 percent) of

small schools have a plan.

3) To enable and extend students learning

Some teachers need further support to know how to enable students to reachthe curriculum level for their year, and extend students’ learning.

- It is still early days for the curriculum, and teachers and leaders are not always sure what the core components of structured literacy or maths are, and where there is flexibility.

- To manage this, leaders told us they support teachers to contextualise what they learn in PLD in their classroom. They put effort in to agreeing common practices and ensuring that teachers have consistent messages, especially if teachers shift

between schools.

- Some teachers report being unsure about adapting their teaching to meet students’ needs, in particular, to support or extend students in multi-year classrooms, or when there is a wide range of ability within a year group.

- They are also uncertain about adapting for neurodivergent or disabled learners. They want further guidance for when and how to escalate support for students who need additional help and more resources to enable this.

It is earlier days for kura and rumaki. While they generally support the changes, leaders and teachers report challenges accessing the supports and using them in their specific settings.

While positive about the support they have received, leaders and teachers report some significant barriers to access the PLD, guidance, and resources they need to implement the changes.

Leaders shared that PLD, guidance, and resources for Māori-medium provision do not necessarily reflect the breadth of the settings students are learning in. This means there is little change in what and how students are being taught. Teachers in rumaki told us they find it especially challenging. They often translate and adapt English-medium PLD, guidance, and resources for their classes, as they have greater access to these.

Some settings are managing to make it work. Experienced leaders told us that where changes have begun, it is because of the capability and experience of both their leaders and teachers.

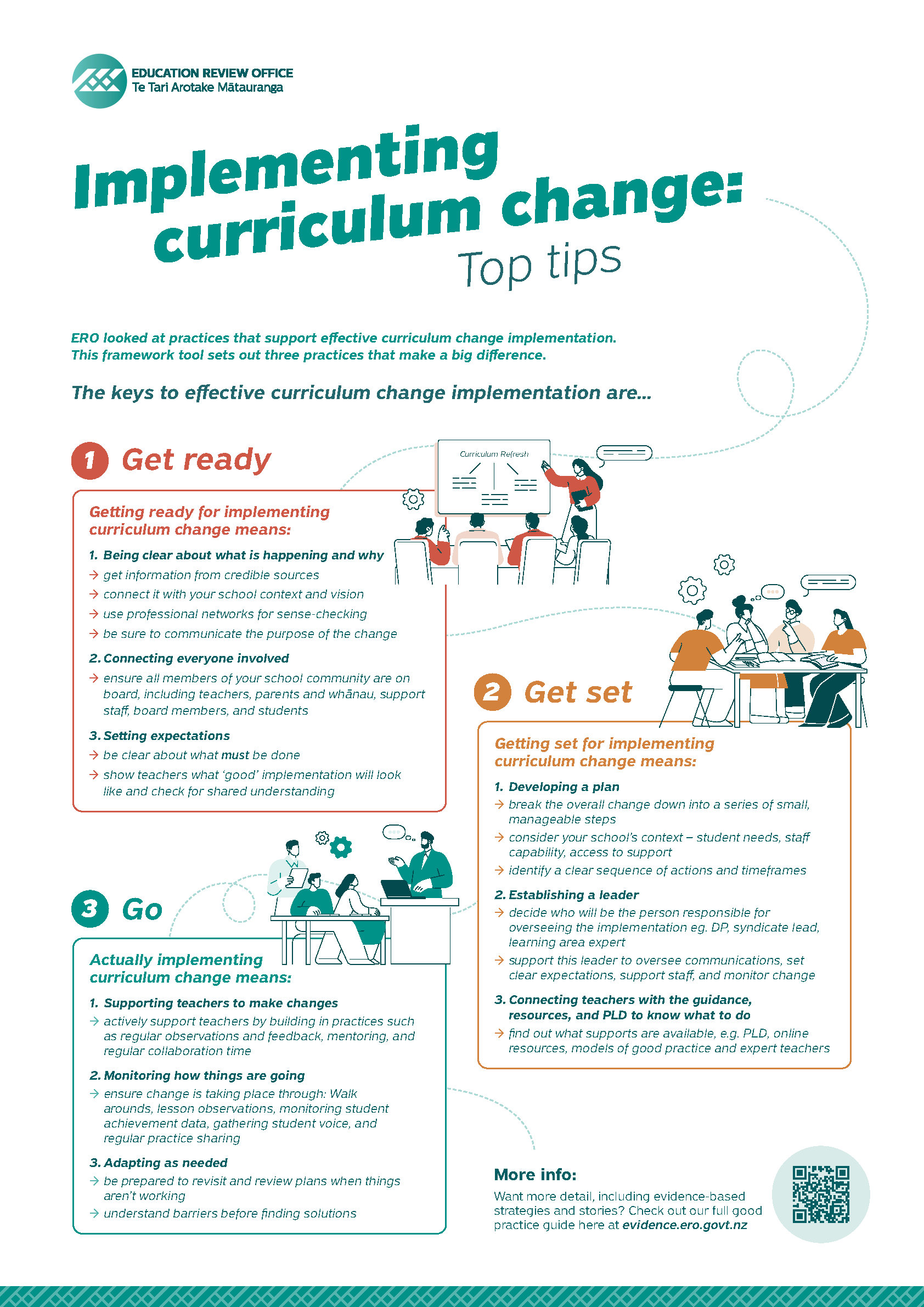

What key lessons have we learned about effective curriculum change?

By reflecting on what was particularly successful through implementation the English and maths learning area changes, and where there have been particular challenges, we identified 3 key lessons to inform future curriculum change.

1) A well-designed curriculum change package can be highly

impactful in igniting change across all schools.

- A clear purpose is key to successful curriculum change. This needs to be communicated effectively so that the purpose is understood by teachers, leaders, families, and the wider community.

- Signalling and sequencing of change works. A curriculum change package works best when it is supported by evidence and tailored for New Zealand’s students. It needs to be supported by a well-planned sequence of changes, and the right support needs to be available at the right time.

- Strong leadership can drive change in schools. Schools make change best when supported by a leader who is responsible for driving the curriculum change and setting clear expectations. Good leaders reinforce and embed changes through supports and resources, and set aside time for teachers to embed learning.

2) Building teacher capability is essential for successful curriculum

change, which makes a difference for students.

- High-quality PLD can build capability and motivation. PLD can change practice in schools when it builds knowledge, motivates teachers to use what they learn, develops teaching techniques, and provides structures and strategies to embed good practice.

- Providing targeted support to teachers who most need it can ensure change happens in all classrooms. This includes building foundational capability where teachers lack confidence or knowledge.

3) Tailored approaches for schools with greater challenges are key to generating change where it is needed most.

- With support, it is possible to achieve the biggest shift in schools facing the most challenges. These supports can work well when provided through a national change package.

- Parent engagement can support the implementation of change. Tailored communication to communities from trusted sources, such as from teachers and school leaders, can be the most successful.

For more information, please download the full report.